The Legacy Series

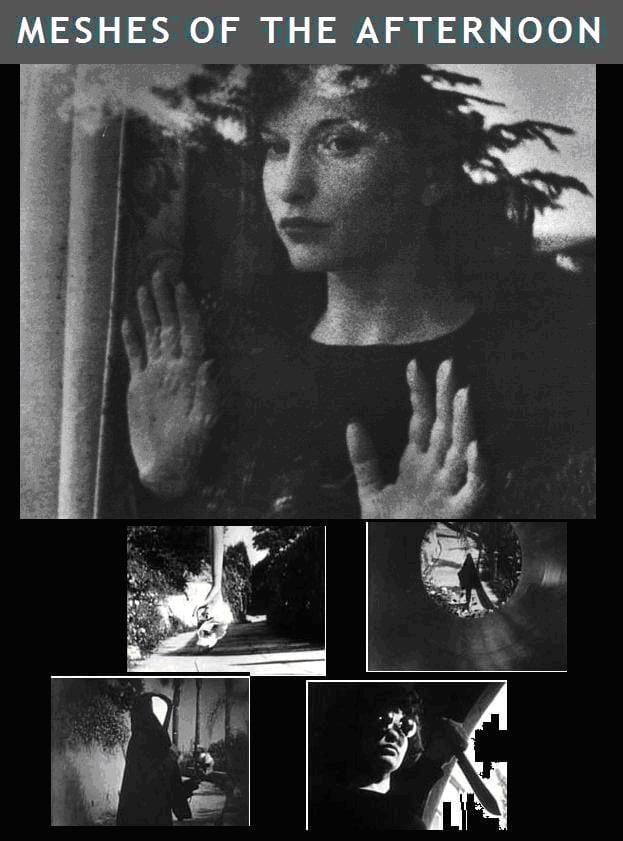

Meshes Of The Afternoon - Narrative And Perceptual Cinema

Much like Un Chien Andalou, Eraserhead or The Holy Mountain, Meshes Of The Afternoon is a film meant to be left somewhat undefined. It holds a narrative, but no tangible plot - the semantic difference between plot and narrative being a palpable idea of a story moving forward; plots are defined as the things that happen in a movie, narratives the bigger, more convoluted, idea. For this reason Meshes Of The Afternoon is a film about ideas. Now, 'a film about ideas' is a pretty pretentious term you hear thrown about a lot, but, if defined, the term becomes easier to swallow. Meshes Of The Afternoon being a film about ideas simply means it hasn't got any true incidental movement to the narrative. We see this captured by the themes that stitch together the narrative. It's the recurring imagery of the key, knife, cloaked figure, flower and mirror that build up the 'story'. In this respect, the 'ideas' this film is about are, in other words, the themes. Thus, it makes more sense to say this is a purely thematic film, that it translates its ideas and story through symbolic imagery. We open on these ideas as they are the crux to understanding or seeing this film in the most coherent light. It's seeing Meshes of the Afternoon through themes and an idea of narrative that enables its presented philosophy of cinema to enunciate itself. However, whilst we've touched on the film in respect to theme, we haven't yet brought up narrative. This is a film usually given the label 'non-narrative'. This, to me, is a redundant, ill-defining term. Narrative means story, more specifically, narrative means a story made up of character, theme, plot, motif, metaphors and a plethora of other filmic devices. I think its important to make this distinction of what a narrative is over pot and the non-narrative because it says to both writer an audience how to judge a story. A story is quite simply a concept, its a very loose sequencing of events. You can tell the same story in a book, film, painting, song, dance, joke - anything. The same can almost be said for plot too. If a plot simply says John does A, B, C then D, then this can in all likelihood be presented in a book, on the stage, on the screen - wherever. But, because a narrative is more complicated then these two things it relies on devices and so the specific form of storytelling supporting it. To clarify, to tell the story of Romeo and Juliet through a poem you would purely rely on words, on verse, measures, beats, enjambment, similes, metaphors - all of the terms crammed into you by high school teachers. What the story of Romeo and Juliet looks like on a page in poetic form is an incredibly nuanced narrative. The romance, scope and emotion of the plot, characters and so on would be told to the reader in a completely different way than a film could manage.

What we're then picking up on with an idea of narrative is a concept of experience. Narrative defines, in large part, the experience of a story provided by the medium or form it's told in. As mentioned, a poem feels different than a film. Some people hate poetry. Reading Star Wars, Fight Club or Casablanca as a poem could kill them - but seen as a film, these stories could be the best thing they've ever heard/seen. This is all because films and poems use different devices. Whilst we have enjambment, stanzas and feet in poems, we have editing, scenes and pacing in films. These different mediums, however, use similar devices and such is made obvious with those like metaphors and themes. All story telling forms - dance, stand-up, painting, composing - use metaphors and themes. However, a metaphor in a book, let's take a cliched one, an ocean of emotions, would be translated as such. Depending on the context used this would mean one thing or another - someone is steeped in happiness, melancholia, maybe a mixture of emotions. However, the translation of the ocean of emotion on film would be a completely different thing. How would that been shown? Would you show a character's face, wrought with emotion, before inserting the image of an ocean? Would you use V.O? Would you superimpose? Would you a transition to a new setting with a huge body of water in the establishing shot after an emotional scene? There are many ways, through filmic language, that this metaphor may be translated. What is important however is that an audience views the metaphor in a completely different light than in a book. It's here that you could delve into the details of a metaphor, the difference between cinema and literature, but the main takeaway is simply that the viewing experiences are, forgive the metaphor, an ocean apart. What this point says to us is that you can take a story, a loose sequence of events, and turn it into a narrative once you apply an artistic medium. Narratives are thus the expression of a form for the large part. However, what happens to this when you bring in an idea such as 'non-narrative'? Frankly, we should be left flabbergasted, simply asking: what the hell does that mean? What does it mean for a film, book or poem to not have devices, to not tell a story via a medium? There's two answers to this. The first is simple: there is no such thing as non-narrative because people are inherently telling 'stories' by translating a sequence of things to an audience through a medium (such as film). These things could be events or ideas however ambiguous. I'm telling you a story right now believe it or not. I'm using a sequence of concepts from plots to narrative to themes as to build toward a point. And it's exactly that that we can suppose is the crux of this argument. Stories, just like narratives, have a point. And everything has a point when seen by someone - it's given or taken, nonetheless, a point is there.

But, whilst there is a good argument for 'non-narrative' not really being a thing, there is a justification for the term - it's quite simply that narrative and plot are so delicately intertwined. In fact, it could be argued that all the themes, metaphors and so on we've been discussing are the meat tethered to the backbone of a plot. In other words, narratives are made up of a plethora of devices, but is primarily the expression of plot. By taking away plot you may argue that narrative falls floppy...

... leaving it something alien, weird, purely thematic, a movie about ideas or... non-narrative. Because there are these two strong arguments for and against the concept of non-narrative, the only way to distinguish the outcome of the debate is to ask of the purpose of the term. What does non-narrative tell us? It tells an audience that they are going to see something experimental, weird, artsy or untraditional. But, from my perspective, having just easily thrown those four synonyms, the term is redundant - it says only what so many other terms can say. More than this, I see non-narrative as a distraction to anyone trying to analyse or understand a film. By understanding that allegedly non-narrative films have stories, have structure and a point, they stop being splatter paintings, empty rooms with flickering lights or signed urinals and become something no more than a few steps removed from Transformers, Paranormal Activity, heck, even reality TV. Whilst it sounds insulting to say that Meshes Of The Afternoon isn't too different from a Michael Bay picture, or pointlessly pretentious to suggest that a Michael Bay picture isn't too different from Meshes Of The Afternoon (whichever way around you want to see it) I see the comparison as a respectful nod to both the medium of film and the audience that consumes it. Meshes Of The Afternoon and Transformers are split apart simply only by the weighting of their narratives. Transformers isn't really very concerned with themes outside of bland, rather empty, statements of patriotism, heroism and morality. In the same respect, Meshes Of The Afternoon isn't really very concerned with robots punching each other in the face. Nonetheless, they are both communicating through narrative and through emotive art. It's exactly this that brings them together and demonstrates a respect for the art and audience - there is an attempt to say something worthwhile as well as show a good story. The reason why Meshes Of The Afternoon isn't comparatively (to simpler blockbusters) a splatter painting is then that it speaks their language and makes a point - never just asks a question. To clarify, a splatter painting, from my biased and rather uneducated perspective, asks more from its viewers than it gives, moreover, it doesn't say much to them. You could argue that splatter paintings are a commentary on form, on anarchy, on automation, on human creativity subconsciously flowing from us. But...

... does that really say as much to you? I think not. I see aesthetic, an artistic manipulation of colour to produce something somewhat captivating. This produces a form of art that is inarguably non-narrative - if we had to use the term. It stands only to capture the eye, its point being only to distract. This triggers one to see Transformers as more a splatter painting than Meshes Of The Afternoon. However, such a comparison would be empty. Transformers' main goal is to entertain, but added to this, it has to juggle character, choreography, editing, writing, themes - a myriad of other cinematic devices. Whilst the Transformer films don't juggle these devices too well, it sets itself apart from a splatter painting by trying. And the main distinguishing factor is that all Transformers films, whilst having a similar purpose, don't just look different, they have to say different things. Even if they don't do this, even if the plot is recycled film to film, that is something you can pick up on as a judgement or critique of the film. When it comes to splatter paintings, they have their point of being purely aesthetic, but no matter how many you produce, no matter how many different strokes you use, you cannot seriously argue they make different artistic points - something that is beyond criticism because of the unnecessary constraints of the medium/technique, something that is then quite clearly not the same calibre of art as a (good) film. A Transformers film can be about a coming-of-age, it can be about terrorism, it can be about betrayal, it can be about love. What can a splatter painting be about? That's a crucial question, one that can only be answered with the preemptive 'I feel'. You can say the painting above makes you feel humbled, aggressive, agitated or whatever, and thus say its about aggression, free flow or displacement. But, where does it says this on the painting? What squiggle, drizzle or drop spells that out? Point me out one, but then do me one favour: show me how that builds into a point, a succinct, intentional statement worth listening to.

It's that somewhat tangential meandering through Transformers and splatter paintings that brings us nicely back to Meshes Of The Afternoon. This film holds a narrative. It's in the themes, the succinct, though ambiguous, sequencing of images that a story is told. From the frames of this film comes a point not just on the medium of cinema (just like splatter paintings serve as commentary on the form of painting) but a point on human behaviour and our reality. It's this exact point that we're then going to discuss, and seeing it will tell us something not just of human perception, of circumstances and situations, but broaden an idea of what cinema can do.

Meshes Of The Afternoon is quite simply a film about perspective. What we experience is our protagonist's, The Woman's, reflection of self through her relationship. In short, it's The Man that is the Grim Reaper-esque figure with a mirror for a face. This is a point made clear with the image of his face in a circular mirror and later his reflection being smashed, the juxtaposition of images solidifying a link between himself and the cloaked figure. And by assuming The Woman and Man are in a relationship (boyfriend/girlfriend, husband/wife, brother/sister, simply friends) we can understand why she thinks of him, why they live together and seek each other out. The purpose of The Man being represented largely by a mirror is to suggest that he is a reflecting agent. In other words, it's The Man that is making The Woman question herself: where she lives, why she is there. It's this simple assertion that makes clearer the meaning of the flower, the keys, the knives and the confusing representation of time. The flowers represent incentive. They are something The Woman picks up and The Man is drawn to. This could, if they aren't family, suggest something sexual as emphasised by the bed scene, or possibly something of beauty, or natural ownership. In other words, The Man wants something The Woman has - her body or something closely linked. This combined with the keys further emphasises the house as a feature of their relationship. It's her way to, or means of establishing, home, comfort, security. To keep the key is to have control - is to be able to keep Th Man out if she wants. However, under the theme of a relationship, a physical key is never going to be enough to keep someone out of your life, out of your thoughts and emotional make up. This is why the key transforms into a knife - a symbol of violence both towards herself (suicide) or him (murder). The key is then her way out of the relationship - allowing us to assume its not a good one. The use of time, of things repeating themselves, The Woman meeting figures of herself, seeing herself in the past, suggests further reflection. She sees simultaneously what could be the mistakes of her pasts as well as the coinciding emotions, thoughts, intentions. What this all says is that we see The Woman on a short journey. She chases the illusive figure - The Man in different form. She cannot find him and so retreats into the house. But, it is disrupted; the phone off the hook suggesting suspended communication, an open, but forever vacant line beyond the world she lives in. In the house she questions essentially what it means to her, what the relationship in this place means. This produces the layering of time and the physical paradoxes that emerge. These all coalesce into the actual Man walking in on The Woman to find her covered in seaweed as if she's been out at sea. A sea of emotion if you'll have it. Another interpretation could be that she drowned in the depths of the emotion, or of change, the tides of it. This all leaves her stricken by her revelation or introspection. She either decided she wants out of the house - the man seeing her drowned figure as a representation of the end of her as his, as owned by him. Or, this could imply she decided to end it all, maybe turn the knife on herself, wade into melancholy, depression, suppression - possibly stay with the man.

With the film briefly explained/outlined it becomes clear we have a film that is about a tragic story, a story imbued with hopelessness and a search for reprieve. (I wouldn't suggest that there aren't alternative interpretations of the film). However, we've seen these stories a million times over in a plethora of differing forms...

What transforms Meshes Of The Afternoon into its own being is the use of these themes to accentuate an idea of perspective. There is no real plot in this film because it aims to be ambiguous, it aims to imply an emotional sequence of events, not a spatial and literal one. This is what makes it an experimental film and an untraditional narrative. It expresses its story not through literal events, but perceived happenings. The fact that The Woman sees this contemplation of the relationship in the way she does speaks of her character, it says she doesn't know The Man too well, that she is many people both to him and herself. Through the images of the mirrors and multiple selves it's made clear that there is something of herself she sees in The Man, that she sees him as saying something about her, possibly something about her own weakness. All of this coalesces into a narrative that is meant to appeal to concepts - ideas of relations, trust, isolation, despair, unknowing - but all to speak of a character and for a character. This is then great cinema as it uses filmic devices in effective, expressive and intriguing ways. Not only does it tell us of something captivating through its imagery, but it allows us to experience them (the story) in an enthralling manner. It's the use of the soundtrack, the editing, the physicality of the handheld shots, the POV, the slow motion, that create an atmosphere that is quite simply entertaining - an enticing cinematic experience. And, as I've said many times, it's the appeal to elements of entertainment as well as more artistic commentary, or an attempt at putting across a point, that makes films great. It demonstrates a care for a movie in respect not just to the audience who endures/watches it, but also the audience subjected to what the film has to say. In other words, as a concept, this film looks good and sounds good, it is both something to experiencing, but also something that has a point to make, something to say.

The takeaway from this film is lastly a philosophy of cinema. Through Meshes Of The Afternoon we see an approach to narrative through character, we see an emphasis on images and filmic devices such as camera movement, the juxtaposition of images, visual metaphors and so on, to express an incredibly ambiguous story, one we have to fill the gaps in by using the provided themes as context. This approach or philosophy of cinema is highly technical, is at first glance a splatter painting, but from behind the chaotic brush strokes comes concise, detailed and irrefutably conscious marks of theme, character and great story telling.

Repulsion - Metamorphic Cinema

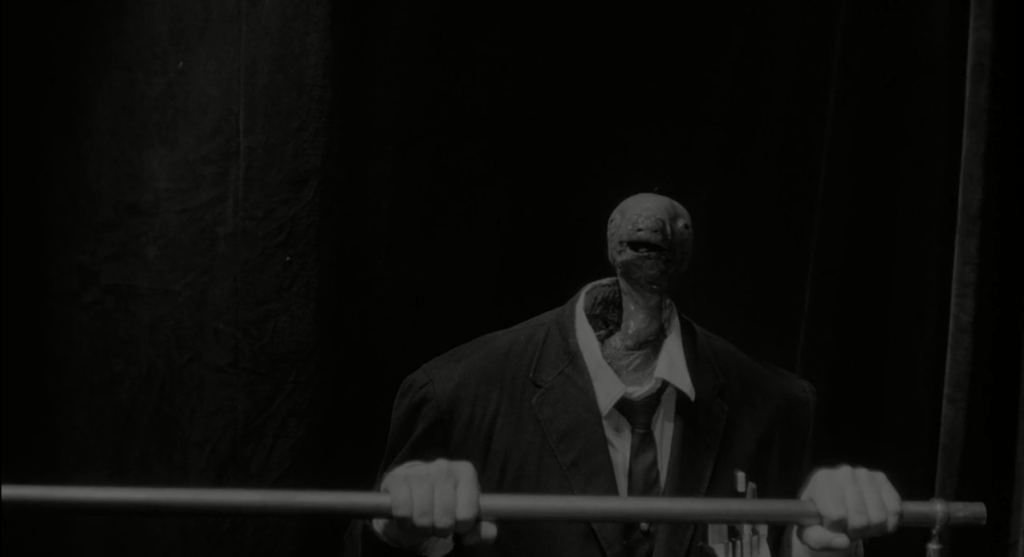

Repulsion is a film that has great influence over me as a writer. The proof of the fact is in the previous screenplay-based-series where I also covered this film. (Links here). But, whilst I talked about the psychological distortion of Carole, essentially pulling apart the film's subtextual narrative for the Receptacle Series, here I want to pick up on the form of the story Polanski tells us. In doing such, I want to focus on the final image...

This image not only identifies Carole as a character struggling with a complex past, but transforms the film entirely. It's this image that speaks as something much more than a plot twist or a crucial revelation in the story. We see films transformed across a plethora of films with endings like these...

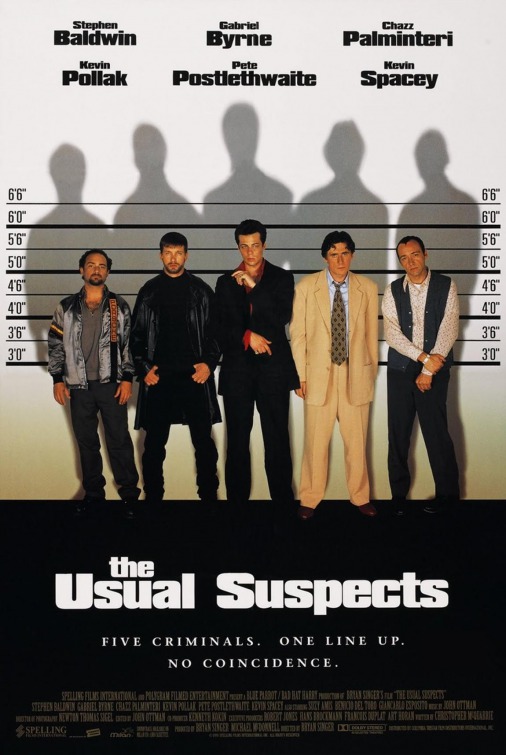

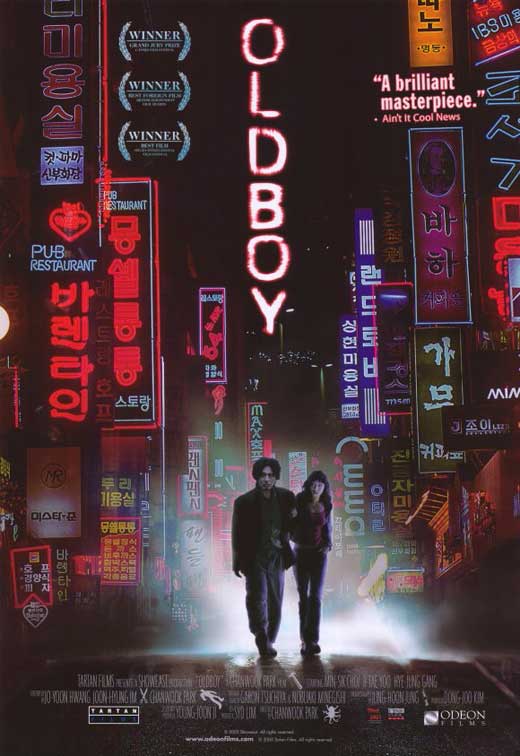

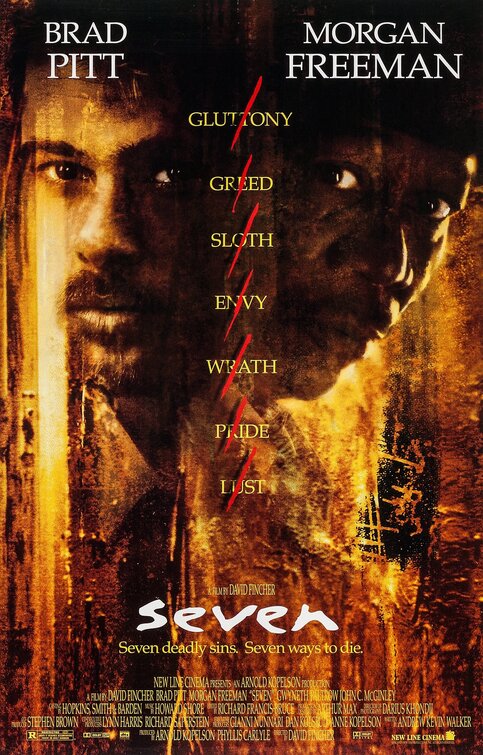

But, as mentioned, the ending to Repulsion isn't just a mere plot twist, it's not really comparable to many of the films above or those like them. The endings to Fight Club, The Sixth Sense, Dr. Caligari and The Usual Suspects all change the physical spaces of their films. To clarify, once we know Tyler is a projection of The Narrator, we rewatch the film knowing that he talks to himself, that he sabotages his own operations. Once we know who Keyser Söze actually is in The Usual Suspects we look at the interactions of characters differently. The rest becomes obvious from this point. Plot twists are there to act like the punch line of a long and elaborate joke. Take for example this one (which I stole from here)...

Little April was not the best student in Sunday school. Usually she slept through the class. One day the teacher called on her while she was napping, "Tell me, April, who created the universe?" When April didn't stir, little Johnny, a boy seated in the chair behind her, took a pin and jabbed her in the rear. "GOD ALMIGHTY!" shouted April and the teacher said, "Very good" and April fell back asleep. A while later the teacher asked April, "Who is our Lord and Saviour," But, April didn't even stir from her slumber. Once again, Johnny came to the rescue and stuck her again. "JESUS CHRIST!" shouted April and the teacher said, "very good," and April fell back to sleep. Then the teacher asked April a third question. "What did Eve say to Adam after she had her twenty-third child?" And again, Johnny jabbed her with the pin. This time April jumped up and shouted, "IF YOU STICK THAT F*****G THING IN ME ONE MORE TIME, I'LL BREAK IT IN HALF AND STICK IT UP YOUR ARSE!" The Teacher fainted.

We've touched on the idea of physical spaces in The Usual Suspects and Fight Club being changed because of the ending. Things such as a film telling us a character was never there or that they weren't who they told us they were is a physical manipulation of space and thus tantamount to a magic trick played out before your face. We know a person with a 'magic pack of cards' is using sleight of hand to fool our eye though. The same thing happens as we're told Tyler was never there in Fight Club - there is a deception. However, there is a cheapness to this trick in cinema. As Méliès teaches us...

... magic on the big screen is astounding at first, but a trick worn tired very quickly. Physical manipulation on a screen is almost a cheat because of editing, because you have tangible control of the film. This is something a street magician doesn't have. A similar thing may be said of films such as Chinatown or Memento. There's a cheapness in being able to use sleight of hand on screen. For this, it's incredibly hard to find films with twist endings that work, that are worth rewatching. In fact, the distinguishing factor for the twist ending films that you watch once or twice for fun and those you watch over and over because they are simply great films is of the physical spaces we've been talking about. The best twist ending movies aren't episodes of Scooby Doo with a nice little unmasking in the end. The best twist ending movies change how you look at intangible things such as the meaning of the film and the relationship between characters. It's this added layer that brings the likes of Fight Club and Memento closer to Repulsion. The twist ending changes the way you look at the film not just in terms of the physical spaces, but the narratives and characters. But, whilst Memento holds commentary on the mind's biases, on its incapacity to deal with the trauma it causes and Fight Club says a lot about the individual's growth (more on that here) the films also strive toward an 'A-HAH' moment. This defines them as films with plot twists as well as narrative twists. We discussed the difference between narrative and plot in the previous post, but to recap, narratives hold plots (a specific sequence of things happening), but overlay artistic devices dependent on the medium - things like character arcs, metaphors, editing, camera movement. With Fight Club we are not only seeing the plot being twisted on its head by the physical space changing (Tyler not being there) but also the narrative being tuned on its elbow by the mental state of the Narrator being revealed as a means of commentating on the plot twist. In other words, the moment of the twist says more about the film overall than just the plot. And because there is much greater complexity in the narrative twist rather than the plot twist, we rewatch the films that have strong ones.

It's here where we come straight back to Repulsion. Repulsion holds one of the most poignant and effective narrative twists. More than this, Repulsion hasn't really got a plot twist - only a narrative one. This is what distinguishes it from the likes of Fight Club, Memento or The Sixth Sense. It focuses on changing the intangible aspects of the film, on imbuing the narrative with meaning, all whilst appealing to a very subtle version of a punchline-chasing format. This produces a complex, evolved kind of cinema that uses an idea of 'meaning' in an astounding way. Because it's my belief that the best films both entertain and have something to say, I'm often faced with a question of where the line is drawn. I love films with symbolism, subtext and metaphors. However, most people don't. For many, the existential themes of a Disney film don't come through - and even when they're explained, they don't count towards much. However, what Polanski teaches us through Repulsion is how to turn the pretentious, artsy side of a film into the entertaining factor. He takes the idea of a twist ending and all the emotive power it can hold, but directs its momentum towards explaining Carole's inner conflicts and the psychological horrors they hold. To me, this is what made my first viewing of this movie so poignant, so revelatory. It demonstrated how to emotionally play the audience as well as mentally challenge them. Moreover, Repulsion presents an artistic challenge. Through its last image, the film demonstrates that it's capable of explaining itself through pure cinema, without words and with one image. The succinctness of this flawed me, the fact that there is so much behind such a simple image made clear the complete control a writer/filmmaker can have over their narrative, not just on physical plot-based terms, but intangible ones too. When you watch the likes of Eraserhead you're left in awe. But, when you watch/read interviews with David Lynch on this film, you're often left somewhat dissatisfied. You see so much depth in his film, but get nothing from him - which can be frustrating. More than this, it can suggest to you that art and artist must remained undefined, that their meaning has to be down to your interpretation, that there was no true conscious drive towards saying something specific. This doesn't make films such as Eraserhead pure splatter paintings; there is a presentation in these movies of something ambiguous and because of this it doesn't always make sense for their meaning/narrative movement to be concrete. Nonetheless, there's something beautiful about a film that can be very artsy, but also conscious.

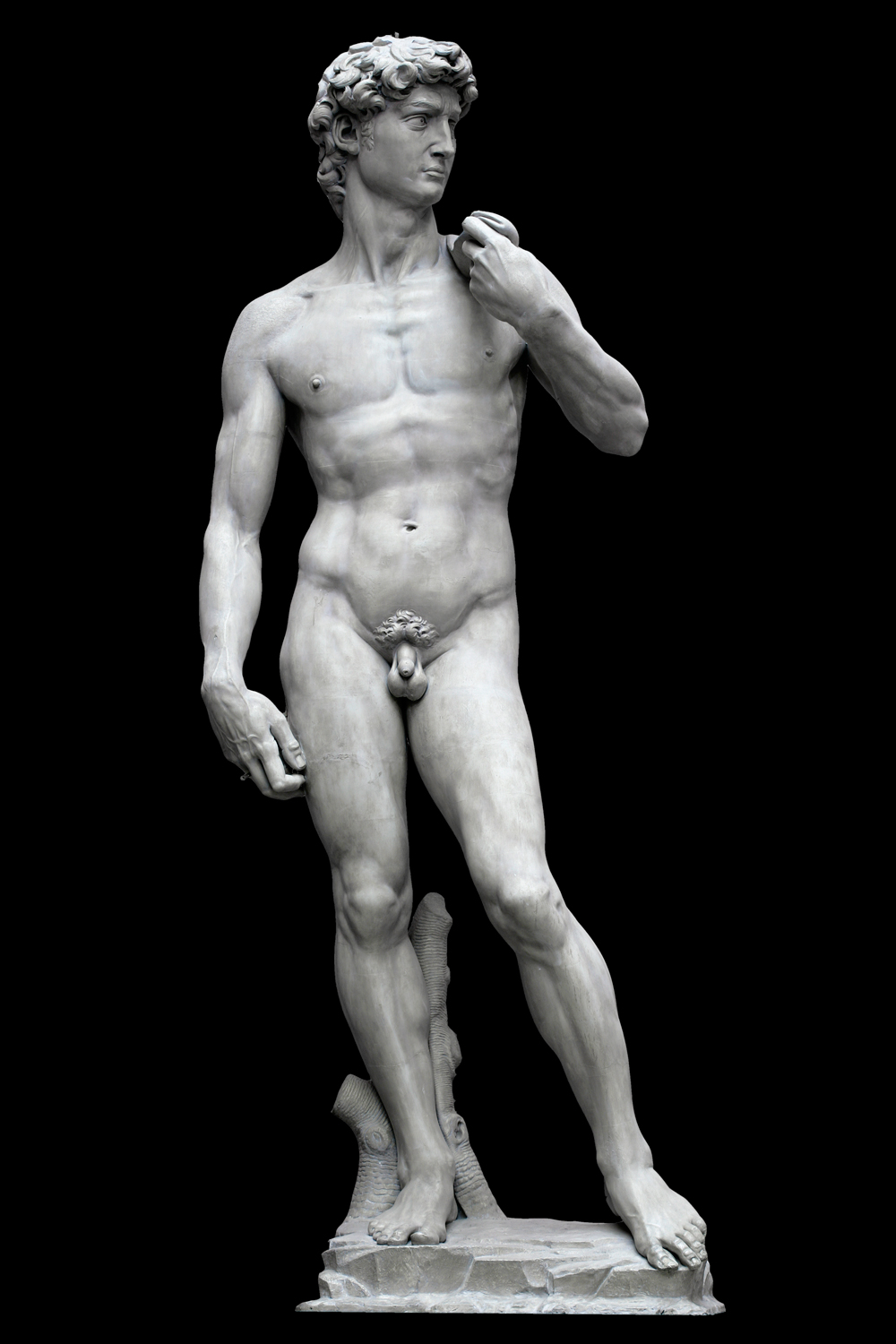

Film as an art form is in large part all about expression. This is because art is an emotional interaction between artist and audience. An artist feels a certain way and wants to share that with someone else via a medium. The medium between them is art - it is the grounds of communication. What we've just picked up on are two interpretations of this connective tunnel. With Eraserhead we see a leaning towards an idea that this channel between artist and audience mustn't be recognised, that, by leaving the means of communication to its own devices, we can be sure that it works best. In other words, it's because Eraserhead appeals so much towards your own opinions, biases, interpretations, that Lynch can say what he intends - even if that is something he refuses and or finds hard to articulate outside of the medium of film. But, whilst there is this kind of artists, this interpretation of artistic communication, there is an alternative. In films such as Repulsion, I see an artist who wants to be succinct and consciously articulate, I see an artist that means to be expressive, but also finds the fun, the joy, his/her reasoning for being an artist in having control over what they say. There is a complex beauty in this attempt towards conscious filmmaking, one that arises comparisons as cliched as those to Michelangelo's David or Da Vinci's Mona Lisa...

In both pieces we see the fruits of years of work - 3 for the statue of David and 4 for the Mona Lisa. This doesn't imply that art should take an awfully long time to create. The time is merely representative of a conscious effort to produce something great, is representative of a long and arduous struggle to control ones art, to present something intentional. With Repulsion's final image, the great depths it implies, I see a similar struggle to control art, to articulate with knowing precision the intention of your movie. This then brings us further away from narrative twists and devicive cinema and into a much more complex concept of filmic art, however, the basic principal still stands. Through The Sixth Sense, Fight Club, Dr. Caligari and The Usual Suspects, we see an attempt to tell great stories. And the key to telling stories is quite simple - it's change. A story is a sequence of things, it's a journey; it's a movement from A to B, from emotions B to C, from state L to H to X to V - whatever your story dictates. All stories imply some kind of change - even those caught by singular images. The reason why the pivotal picture in Repulsion, Da Vinci's Mona Lisa and Michelangelo's David, can be still items trapped in space without time is because there's an implimence in their being that suggest something beyond themselves. With David we see an idea of beauty, of human form, stature and presence. For this, the stature captivates. With the Mona Lisa, we see the character behind the face that tells something of a story, that begins to imply something more than a blank space. With Carole's childhood picture, we are seeing more than a sullen look, we are seeing her past in juxtaposition to her presence. In this idea, we see story, we see meaning, we see the attraction to art in the implimence of context - that banal imagery or physical presences are attached to something more than themselves, that through them we have stumbled upon a journey. What's most important is that through these windows to journeys we are finding stories, we are finding change through the said idea of context. In such, you can understand how Polanski identifies such a poignant image. He picks up on a crucial idea of change in Carole's life, he expresses how this was her years ago...

... but that this is her now...

What this does is build a story and an interest from the audience that invests them in seeing the film through, to allow their imagination to stretch beyond the physical confines that the art exists in and into the immaterial space it implies. In such we see the purpose of art to an audience as taking them on a journey, as implying some kind of movement from a here to there. Great art such as Repulsion not only takes the audience on the journey from the beauty salon with the spaced-out Carole to the sordid, festering apartment full of Carole's projected fears, but opens up the world of the story and character to the audience. This is what facilitates my writings on the film. I'm lead to discuss the inner workings of Carole's character, her past, the hidden subtext of the narrative by the implied grounds of the story that haven't been physically put to film. That means the journey, the story, given by the film isn't just a simple A to B tantamount to a singular level in a Mario game. This is what a lot of mediocre films are, they see art and story telling as a simplistic here to there, they express little more than a means to an end. What's pivotal is that no matter how flashy you make the film with good acting, great cinematography, a good colour pallet, you are only upping the quality of the graphics card, or at most making the level of the Mario game more difficult. The beauty and evolution of gaming towards open worlds then speaks perfectly to the analogy at hand. Repulsion doesn't have you hit the end of the level or walk into walls, transport back on track when you hit the water. Repulsion leaves the story and world it implies open for you to explore on a temporal and philosophical level. Whilst we can't physically see all inches of Carole's house, talk to her or the characters surrounding her, we can use the given information to understand something larger than that, that there is a two-way conversation between art and artist because the film contextualises itself in relation to ourselves by giving us a premise, by guiding us to see themes and ideas - but on our own terms.

In the end, it's Repulsion that speaks most clearly of what stories can be, of how we can use an idea such as art to articulate an entertaining journey of change, but also a succinct point to an audience. Its final image is then a tangible representation of how you can bring stories into that higher dream space and grip the mic by the stand in preparation for your speech.

Witch's Cradle - Imagery

I don't much like this film. It's overwhelmed with empty images that don't build into anything resembling a story, a point or a narrative. In saying such, I see no purpose behind this picture, I see nothing to be zoomed in on and picked apart. This may be for lack of trying, however, it's hard to delve into the details of something that doesn't capture your imagination or attention very well. Nonetheless, this is a very interesting film to me, not on the basis of it as a story, or even as a film, but much rather as a movie poignantly depicting a technique: the use of imagery. This film, much like Meshes Of The Afternoon, has a precise concentration on imagery in an attempt to translate a story by essentially creating its own language that we inherently understand. But, this is something we'll get onto in a moment. As said, the imagery in this film is overwhelming - and Meshes Of The Afternoon is probably the best film to use as to comparatively explain why. Deren, in this picture, attaches with great succinctness, all imagery to a character. This somewhat reduces or transforms the abstract quotient of the film--and is a very important thing to do for an audience. With abstraction in art you are essentially telling a mystery, something not much different from the likes of...

The key to telling a great mystery is in the information you divulge. A great mystery slowly gives you tiny details of a case, it uses character as a vessel to take you on a journey of gradual discovery. However, to keep you interested, mystery writers have to inject twists, turns and silent revelations into their narratives (Twists, Turns & Silent Revolutions is now going to be my new band name). To keep readers/viewers riveted, a good mystery has you on the edge of your seat by simply having you want more - but only because you've had a taste of something good. It's a bit like Pokemon - insert slogan. Using imagery to varying degrees of abstractness follows the same principal. You start very ambiguous, but with intriguing images such as...

... and from there you build, you imply a backstory, a movement or growth of character that you can attach to and use to comment on the film. In Meshes Of The Afternoon we see The Woman chasing the cloaked figure, constantly finding herself lost until the end where she is implied to have drowned. There is a progression here, an A to B, and the images given to us in between (everything from the key to the flower to the knife) are there as clues of the mystery, the mystery of why these abstract images are being shown to us and what they mean. This, in my opinion, is the fundamental reason why you'd appeal to abstract imagery to tell a story. It adds ambiguity and so opens up the planes of meaning. In other words, by having a non-concrete plot or narrative, you are engaging the viewer in an artistic, introspective and philosophical game. The game is to not just give the film meaning, but to take all of your implied points of meaning and articulate what they say as a whole. In this sense, we see experimental film as well as abstract and or surreal cinema as an attempt to entertain - an attempt to entertain in the same respect a mystery would. For this reason, I find the film at hand, Witch's Cradle, both an intriguing attempt to test the boundaries of cinema, but also a caution as to where I'd want to go. Its faults lie in the lack of movement, the fact that there is no announced or compelling progression of events, just a lot of things going on with string under the loose theme of traps/games. It's then this kind of film that moves toward the realm of splatter paintings for me - it's an approach to art I find no sense, interest or joy in.

However, I don't want to focus on why I don't much like this film, instead try to articulate what it best teaches - to anyone who doesn't really get it, and doesn't really want to. This kind of film is hard to criticise beyond saying 'it doesn't interest me much'. But, it's also this kind of films that can easily be defended by saying 'you just don't get it'. This creates a vacuum whereby the only means to an end is to agree that the two opposing opinions disagree. Why do they disagree though? Why do some people say they get it and why do some people not? I see the answer in the inherent purpose of imagery. As touched on, imagery is an artistic attempt to simultaneously create, teach and communicate in a new language. This means that films such as this, Meshes Of The Afternoon and Eraserhead, are like a Spanish speaking teacher trying to teach an English speaking class how to create new Spanish words for the translation dictionary they're going to create. The same can be said for almost all abstract or untraditional form of art (new kind of art we're not exposed to often or used to). But, to clarify on the point of imagery and language, films don't talk to us primarily in words. Let's take a famous example of classical Hollywood cinema with this:

Hitchcock, without stuttering, tells us that Marion is running away with the money because of her feelings for Sam - her boyfriend. This is cinematic language, this is using imagery to communicate a story or point. However...

... what is Lynch saying with this? It's not as simple as Marion undressed, stressed, wanting to escape town with the motive of being with her boyfriend. The Lady In The Radiator is an abstract dream of Henry's, one connected his girlfriend, his drifting sexual thoughts and desires, the baby he's been left with and the 'In Heaven' song. With Eraserhead, unlike Psycho, we then get a network of images that work together at unclear distances across the narrative. So, whilst Psycho talks in direct, simple sentences, "Marion wants to leave town with her boyfriend. Having taken thousands of dollars under good trust, she is now undressing, bags packed", Eraserhead talks in circles, tangentially, fingers poised and waving...

What this says about cinema is that there's two approaches to 'talking', to translating to your audience a story through images. There's the direct way and the abstract way. Few films sit on either end of the spectrum, but somewhere in between. However, with Witch's Cradle, Eraserhead and films alike, we get pretty close to the extremes of abstraction. In doing such, we are experiencing the impossible Spanish class touch on before. But, what is probably the most fascinating thing about cinema is that with successful abstract or surreal films we understand the class - we come away with a complete book of personal translations. Having said that, it's important to recognise that Eraserhead and Meshes Of The Afternoon are clearly not too far cut from Witch's Cradle. Nonetheless, Witch's Cradle is the kind of film that is abstract, but to the extent people (I for example) might not get like they would the others. So, again, we're sucked into the vacuum; I don't like the film, but maybe I just don't get it. The question also arises again: why must the two opposing opinions be polar to the point of agreeing to disagree? It comes down to communication. With Eraserhead as my absurd Spanish teacher, I can come away from class with a book of translations I feel comfortable with. With Witch's Cradle... I got nothing worth bragging about.

Now, I understand that all that I've just said is pretty redundant and circuitous because I've kind of explained why the imagery doesn't work for me already. However, I mean to pick up on a larger paradigm of films we get and films we don't get. The reasoning behind us not getting certain films is down to miscommunication. Beyond why or how this happens, I think there is something much more macro and micro-cosmically universal going on. By this, I mean, through something as conceptually banal as 'imagery', we see an existentially intimate and vast relationship between people and the world around them.

These images focus on string as a webbing that possibly trap a woman or couple. In such, I see the presentation of an image, of imagery, as the use of a physical presence to communicate an intangible being. We see the string as an attempt to talk about the intangible concept of the couple, their relationship, feelings and so on. (Though, I'm not too confident in this analysis of the film). Nonetheless, imagery is all about using the world around us to communicate how we (characters) perceive things. It's with this definition that we can see all the better the difference between Psycho and Eraserhead...

With Marion looking at the money we are seeing the intangible concept of her feelings articulating themselves - it's emoting/behaving/acting that tells us the story here. With Henry stood before The Lady In The Radiator, it's not enough that he seems scared, that The Lady seems sweet, that the actors underneath the characters are portraying emotions. Their physical presence isn't doing much of the talking - instead it's the film around them:

The same attempt is being made in Witch's Cradle - the attempt to communicate internal ideas of the characters through external and physical objects...

What inhibits this expression or communication between myself and this film just as it may you and Eraserhead (any abstract film you don't get) is the fact something is malfunctioning along this line of communication. It's either me, the image, or the character on the other end. What myself assuming that the film, the characters or imagery, are at fault says is that the filmmakers have failed to prove to me that they or they're characters exist. I know, existential, but let me clarify. The whole point of using physical things to talk about intangible ones is that the intangible ones can't speak for themselves. We'll hold onto the idea of Marion in Psycho to delve deeper:

Yes, this is a direct example of an expression of character, but, on a fundamental level isn't. We're being told of Marion's plans to run here - we're being told of her imagination. However, her imagination isn't physically telling us that its going to use this human body to take this paper and run away so that the brain it's attached to continues to pump out the good drugs: love, happiness, comfort. Such is obvious; we're not telepathic. Instead, humans are built to read facial expression and body language. And so, it's the image above that quite literally has the capacity to speak up to or more than 1000s of words. It's the physical presence of Janet Leigh as the middle-man that connects the lines between Marion Crane's imagination and ours. What's interesting is what this says about these images:

Deren, Duchamp and Lynch are in the business of employing new telephone operators to connect lines.

Instead of using actors, they use flowers, knives, string... weird, foetus things. It's the artistic exploration of imagery that is the human endeavour to better communicate. It can be in French, Latin, Spanish, on paper with words, on stone with hieroglyphs or on screens with emojis, but people constantly strive to say things in ways that better communicate their hidden internals - their mind hidden behind their eyes - to the internals trapped in other people.

And it's here where we come upon the crux of what imagery is. Abstract, simple, somewhere in between, all imagery is the endeavour to best say that we are alive, that we exist, that there is something going on in here. Imagery in film is just the attempt to speak in a unique language that hopefully communicates succinctly who we are and who characters are. Keeping this is mind, we have the tools to better tackle the concept in application. What's more, to the stand-still vacuum presented by you saying "I don't understand this film and I don't really want to" and someone else retorting, "You just don't get it", you can now just reply: "I just don't think the film exists". Sure, there's still an agreement on a disagreement to be had, but also a pretentious segue into a debate on the existential tangents of imagery. And if that keeps people talking, well, that's kind of the point, what we all seem to want: to keep yammering on about ourselves.

The penultimate film in the Legacy Series and the last post to cover an experimental film by Maya Deren.

This is a simple yet awe-inspiring film. It takes a home-grown approach to the idea of a documentary and turns it into an almost fictional narrative. We see this in the use of POV, the intimacy of the shot types that always keep us close to the cats, but most importantly in their personification. Documentaries are quite obviously the documentation of real events, the goal is to portray literal happenings, not manipulate them. With the use of POV and the emotional telling of this story we are feeling the hands of the directors (Deren and Hammid). This manifests itself in the form of personification, in us seeing the animals as characters, as beings, through comparison to ourselves, somewhat understandable. This injects the fantasy into the narrative, slowly pushing it further from a 'documentary'. However, in saying such we enter a semantic debate. If you look to almost any documentary on animals you'll hear personifying terms, things such as 'he', 'she', names of the animals (not Buffalo or Lion, but Ben or Lenny), emotions of them, their internal intents or thoughts. This is all delivered in voice over by the likes of the legendary Attenborough and is there to turn what is often random pieces of footage into a cohesive story, into a captivating narrative with characters and emotions. This is the accepted format of modern documentaries and has been for a long time. However, I'd shy from calling them just that. To me, these are most coherently documentaries...

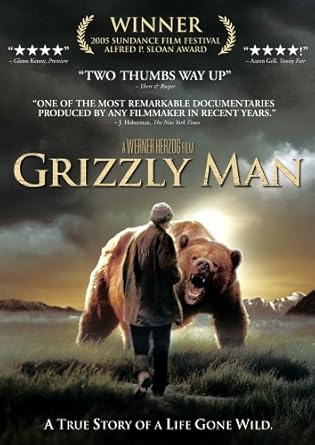

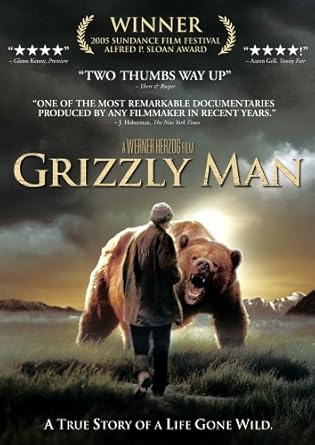

These films are about people, real events involving a skewed portrayal of a mundane reality by design. In other words, all of these films have an agenda, they mean to portray something from a predecided position or bias - especially the first two. However, because the subject of these documentaries focuses on the biases of Michael Moore, Herzog or Coppola, we are supposed to see the documentation of what is essentially their perspective. The reason why something like Frozen Planet or The Private Life Of A Cat cannot really be put into the same category as these films is that animals cannot project their own perspective by interacting with the camera of giving their own voice overs. This essentially means that there's a documentation of an external bias in these films, that the source of documented commentary has little validity as it doesn't portray exactly what it set out to do. However, this is where the semantic debate of what is and isn't a documentary becomes almost trivial: you can't document an animal's internal thoughts or emotions. This leaves filmmakers resulting to V.O and personification to sell the documentary. This, for me, isn't good enough reason to call the likes of this film or Frozen planet true documentaries. That's simply because they approach the narrative without a stated or explored philosophy of what animals are. This is what Grizzly Man, in part, does. It asks how different animals are from ourselves, if we should or can pass the 'Invisible Line' between ourselves as one species and them as another. If the likes of Frozen Planet explored this question, if it looked into the biology and psychology of these creatures before personifying them, then I believe we'd have a true documentary because there's an established bias or accounted perspective. As mentioned though, there's another distinguishing point of what is and isn't a documentary under the guise of form...

I love Man With A Movie Camera and bring it up almost every time I touch on documentaries, but I don't really see it as one. Man With A Movie Camera is just a film to me - a fictional one. Because of the film's form, its technical focus on direction, editing and camera operation, I see its crux in the manipulation of reality to convey a narrative point. The same can be said for The Private Life Of A Cat. This film is not about documenting how cats live, it touches upon foundational ideas of life - society and reproduction - and keeps its focus there. By using POV, tight framing and personification it means to have us think about ourselves, about existentially human concepts before a feline perspective. This is a crucial distinction in my opinion because it truly opens the cinematic gates. By assuming everything containing a camera on a real person is a documentary we wouldn't have fictional cinema. Moreover, we wouldn't just be calling all films documentaries, but we wouldn't have action, romance, fantasy and science fiction on screen as we would now. By assuming an approach to cinema that was dogmatically documentary-centric, filmmakers' fundamental question when approaching a script or premise would be: how do I make this real, how does this reflect reality? This means that verisimilitude, making things believable and real, would be the primary judgement of a film as good or bad. This would ruin cinema as we know it. We couldn't have a Hulk, Terminator or Godzilla. They would all be a ridiculous gimmick that'd make no sense under the laws of documentary - it'd be silly people using films to project childish imaginings, not comment on ourselves through entertaining bodies or forms (Hulk, Terminator, Godzilla). All films under the law of documentary - this really should be a sci-fi film about the first director audacious enough to make a blockbuster - I've said it here first, so if any of you wants to steal the idea, I want story credit, ok? Anyway, all films under the law of documentary would be strictly dramatic, would be at the most extreme, shitty reality TV.

Having recognised this hypothetically fundamental approach to film where we wouldn't see, let alone accept, actors as actors, as people pretending to be other people, we can now turn back to documentaries on animals. There's not really such a thing as animal actors - outside of reality TV (burn... I know). In all seriousness, there's no animal actors. We've had birds, apes and dogs that star in films, but that was a gimmick, that was a bit of fun or for the purpose of children's movies/programmes. What this says is that we kind of already live in the sci-fi Documentary Law world in respect to many 'documentaries'. The whole reason why the likes of Frozen Planet are boarder-line documentaries is that we find it quite difficult to bridge the gap between animals in respect to fiction and documentary cinema.

What we see here is the closest we get to using animals seriously in fictional film. What's interesting though is how quickly things turn childish and then complete shit. I've not see War Horse so I can't say anything about that, however, I don't really like any of these films. Some, such as Marley & Me are fun, but not really much more. What this says to me is two-fold; firstly, The Private Life Of A Cat is in fact quite a special film, and secondly, personification in film is a difficult thing to pull of.

We'll zoom in on the latter first. Personification is a hard thing to pull of for many reasons. The most obvious is that we don't understand the psychology of other species very well and that you should never work with animals (or kids - or reality TV stars - burn...). But, beyond physical application and filming, personification is difficult because its not too different from this...

Yes, you could say it's racist, insensitive, this that and the other, but, to me, this is first and foremost a terrible artistic attempt. It's a combination of bad writing, bad acting, bad make-up and direction. One day when we create chips that we can insert into our own and animal's heads as to talk to each other, they'll be looking at this...

... as the same thing as the Landlord from Breakfast at Tiffany's. All of this would be misrepresentation, oppressive, prejudice, and if you're laughing, plainly hateful. But, it's at this point I'd like to note, I don't like dogs or cats, I'm miserable and aren't drawn to this subject because I'm an animal lover, like to look at these pictures, think they're cute or whatever. Why'd I have to say that? I don't know, I'm miserable. Either way, the point is that in the same way you can 'white wash' human characters you can also 'human wash(???)' animal characters too. You can put onto bodies misrepresentational disguises to entertain no one but yourself. Do I think this is the end of the world and that we should all be calling PETA? No, not at all, I couldn't care less. The point being conveyed, however, is the need to personify dogs, horses and cats is one born out of a miscommunication.

Now, hopefully you've read the last posts (link here) because we're going to be picking up where the talk on imagery left off. Art is all about communicating, from our internal cages, from our minds trapped behind flesh, goop and blood, to others that we exist. Communication can be done through words, writing or art. In the same way these squiggles communicate my internal thoughts to you, so would a painting, dance or film. How successfully and poignantly a movie, performance or painting does this is the measurement of good art. Art is then there to find new way to communicate things with (hopefully) greater accuracy and weight about ourselves to other people. If you look at this concept under the idea of imagery, you could say that all images in a film, each and every frame, is a painting that has a thousand words. Now, the further implication of this is that everything in the frame is an expression of an artist. So, when we look at this...

... we are seeing the art of Tom Hanks as an actor, Roger Spottiswoode as the director, Adam Greenberg as the cinematographer, and a whole bunch of people as writers (Michael Blodgett, Daniel Petrie, Jack Epps Jr., Dennis Shryack, Jim Cash (how many screenwriters does it take to screw in a light bulb, huh?)). However, you wouldn't really say that you are seeing the art of Beasley the dog here, would you? Because the answer is no, we are seeing the art of the director, actor and writers expressed through him as a vessel. This is called personification. Personification is then the use of animals (any non-human objects) to talk about ourselves. We are seeing Hooch personified as aggressive, as protective and territorial. Now, here again we delve into a somewhat trivial debate of semantics. Can you really call a dog these things? Or are these human words with human definitions that, when dogs and people get the cross species communication chips, the dogs disagree with? I lean towards the idea that dogs wouldn't call this action territorial in the same way people would. People are territorial out of our compassion or love being confronted by fear of threat. We protect our homes not just because they are where we lay our heads, but because they are where the people we love live. We are territorial to protect them. Are dogs territorial for the same reason? Are they protecting their owner out of love? Or, are they just protecting the guy who gives them food? Is that love? Is love protecting an external possession or goal, things such as the material items our loved ones may provide us, but also the chemical rushes they facilitate within us? There's so many questions here, and we're essentially questioning Herzog's 'Invisible Line', but in recognising there is a line, that humans and dogs are quite different, I think there is some point of agreement whereby we see the use of animals as an expression of our own thoughts more than theirs.

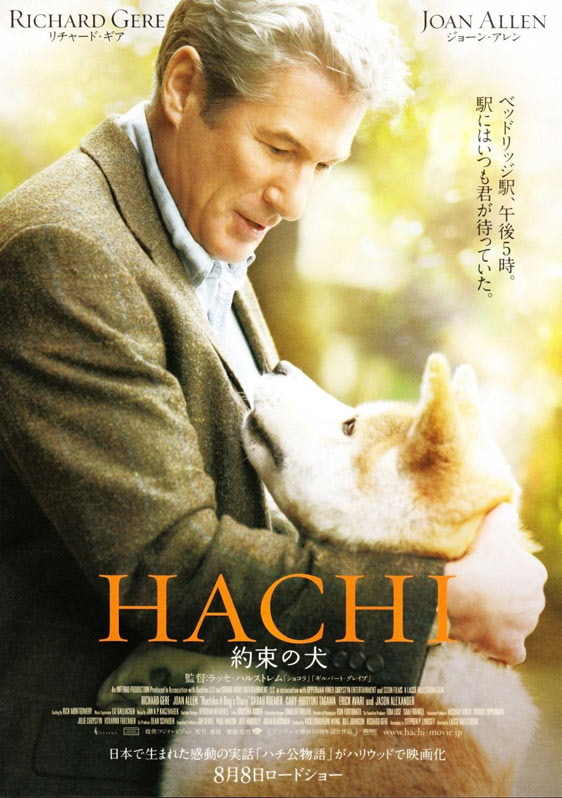

This point of personification is interesting as it mechanises the artistic process, it essentially demonstrates why we do it. Personification is there as a means of communicating through the world whilst simultaneously manipulating in. What this does is layer the subtext of artistic intent. By using a dog to communicate a story about friendship as in Turner and Hooch, you expand upon the theme of relationships as presented by Tom Hanks' and Mare Winningham's character. This is probably a talk for another time, but the character arc of Turner and Hooch is there to show how a man can go from secluded to open. It's there to detail the subtle progression of a man obsessively cleaning out his fridge in the middle of the night, to raising a family. It's the personification of Hooch here that is probably my favourite example of the use of animals in film as it communicates each step of this change in Turner perfectly. The darker themes of the film, one's of crime, violence and death, really bring down the cheese factor present in the likes of Marley & Me, Free Willy or Hachi - which further helps. However, we're getting slightly off track. Understanding what subtext mechanistically can do for an artist, we can come back to The Private Life Of A Cat. In the same way Turner and Hooch comments on a single man becoming a married one with a family life, we see an experimental reflection of an idea of family in Deren and Hammid's short. The beauty of this film is probably in your first viewing of it. The subtle personification of the two cats as a couple proceeding the birth of their children strikes you with a profound conception of a movement in life, of what is quite simply birth. Also, consider this specifically in the 40s, a time before you could easily watch people or cats give birth on TV or the internet. This film focuses on what the title suggests: a Private Life. It's not as much about the cat, but a private life of all things, the profound experiences we keep to ourselves and those close to us. This, for me, is what the film conveys beautifully and is the source of the awe it inspires. What this film in fact reminds me of is the bubble of feelings surrounded by 'first times'. Think of the first time you went to high school or saw a naked person in a sexual context. These were pivotal moments of your life. However, think back to your first contact with these ideas and you're likely to think back to movies, to teen films you watched as a young kid wondering what its like to be a 15/16/17 year old 'grown up', to the first crush you had on a girl/boy in a movie. There's a myriad more of examples like this, but they're all bound to a beautifully naive idea of a first contact.

To me, The Private Life Of A Cat sits on the periphery or in silent commentary of this kind of feeling or concept. The whole point of showing something private in this respect is to present something almost taboo, but at the same time intriguing and somewhat educational. In the digital age, with the internet and so on, these kind of experiences are brief, but multitudinous. We can Google anything, anything, from porn to people having surgery, giving birth, being beaten up, killed, humiliated... whatever. We can expose ourselves to these profoundly abstract parts of life without enduring them or maybe before we're even meant to. That's, for a lack of a better word, pretty special. It's the crux of a digital revolution in society. We don't have to rely on rumours and our stupid friends telling us about breasts feeling like sand-bags...

... or a vagina looking like a fleshy flower, the predator's mouth if he had a moustache. We (kids with phones and so on) can hear stupid shit like that and then just Google it. The existential learning curve of society is steepening at a tremendous pace, and as they say, knowledge is powerful; knowledge is not having to rely on misunderstanding, incoherency, lies, fantasy and superstition. The Private Life Of A Cat taps into all of this from the 40s under the theme of life and birth, but also presents an unfathomably poignant cinematic lesson in what personification is. Personification is often the abstract telling of these private pockets of truth. What makes this film special is its intent to show something so deeply intertwined into the mysteries of life through an artistic and cinematic lens; a great lesson in life and in the application of your art.

The final post in the legacy series.

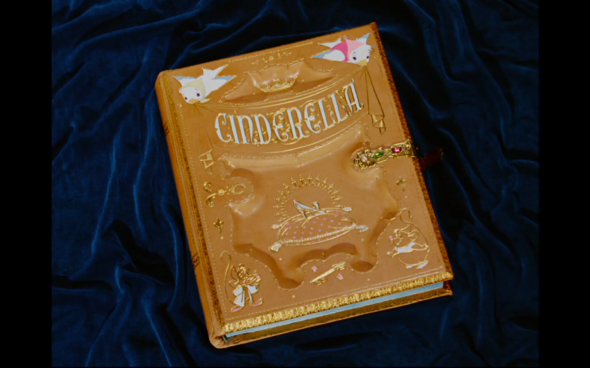

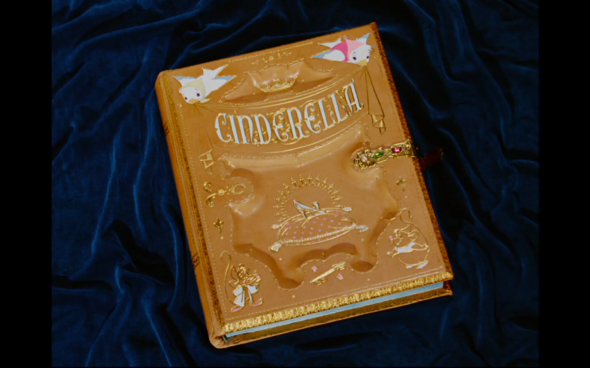

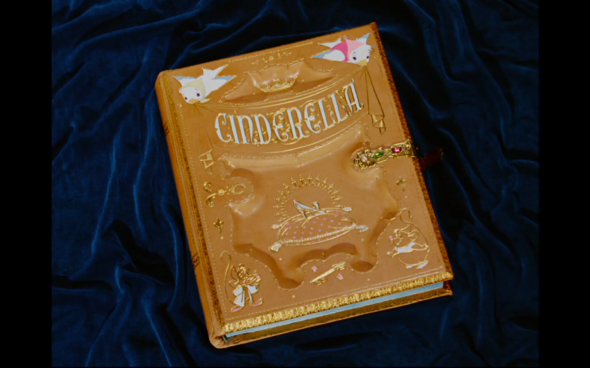

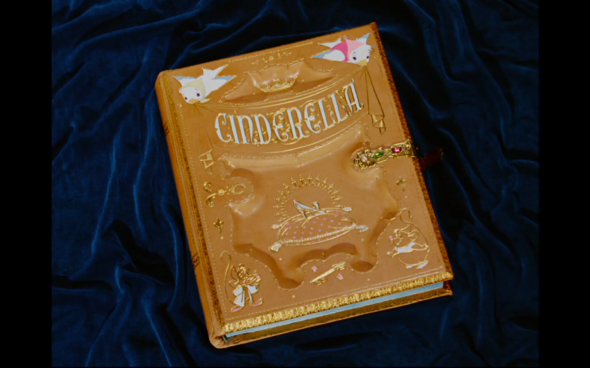

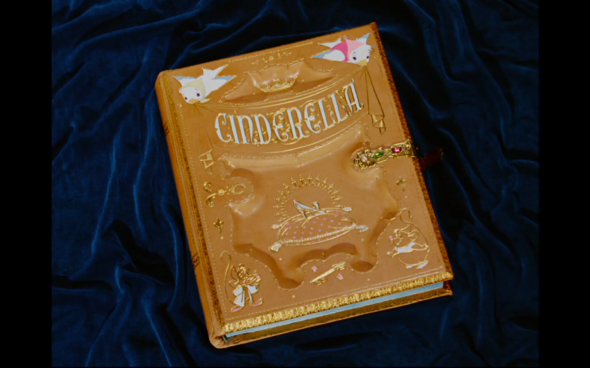

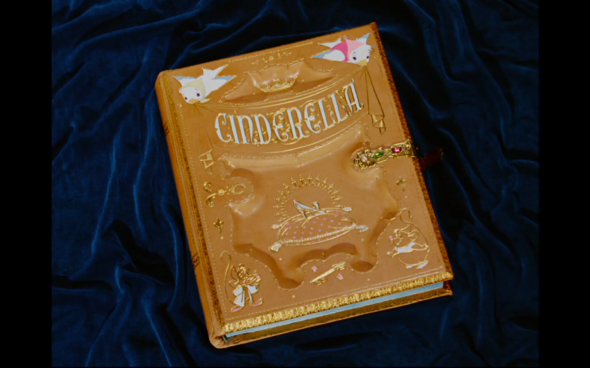

I love Cinderella. It's one of my favourite films of all time. I've written about it for the Disney Series and in connection to another screenplay, Inaffection: The Absence. You can find that post here. I would advise reading that for two reasons; the first, it'll change the way you look at Cinderella, second, I'll be heavily referencing everything discussed in that post. If you don't care to read that, but are still here, well... fine. Cinderella is essentially a psychological thriller. The mice, birds and so on are a projection of her hidden psyche which evolve the narrative into an exploration of inner strength. Keeping that in mind, I'd like to throw a quick overview of the Legacy Series at you. We started with Meshes Of The Afternoon where we explored the idea of narrative and non-narrative. Next was a revisit to Repulsion where we looked at a how Polanski revolutionises his plot with the final image. With the proceeding two posts on another two of Maya Deren's experimental films, Witch's Cradle and The Private Life Of A Cat, we looked at two devices of narrative: imagery and personification. All of these posts essentially discuss how to manipulate your narrative, to inject something exciting and revelatory into your story. What has then been discussed across all of these posts is both what art is and a narrative is. The two major take aways are that art is about a communication between an audience and artist, and that a narrative is there to facilitate that communication by building off of the bones of a plot. In this final post I want to bring everything together under the idea of plot, which we haven't really gotten into yet, and so discuss what Cinderella being a psychological thriller can teach us about screenwriting - maybe writing or creative production in general.

To start, I'll essentially repeat the title: there are 3 plot lines in your film. To clarify, there are 3 types of plot lines in films, but you don't have to really appeal to all of them. You'll hopefully have decided what you think the point of writing/making films is before this, and so be able to determine if you agree with this philosophy of script writing. Ok, so the first plot in your film is going to be the obvious one: what happens. Let's look at Cinderella to expand. If you were to note down all of the major plot points of the first act, you'd get something like this:

1. Introduce the film through Cinderella's back story.

2. Open on Cinderella singing her song, getting ready before showing her morning routine.

3. Introducing all the characters of the film, establishing the conflict between the mice and Lucifer before demonstrating the control the evil stepmother has over Cinderella.

4. Introduce the second act via the end goal of the movie (the Prince finding a bride) before linking that to Cinderella herself. To complicate matters, remind everyone of the conflict to come.

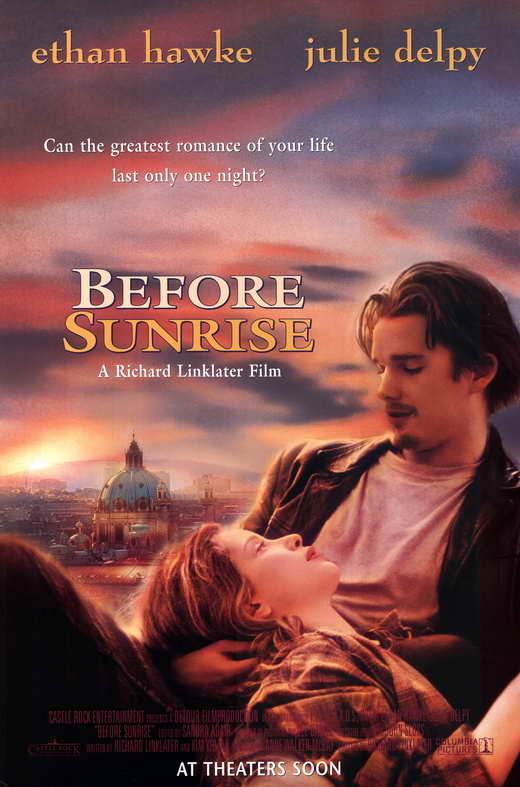

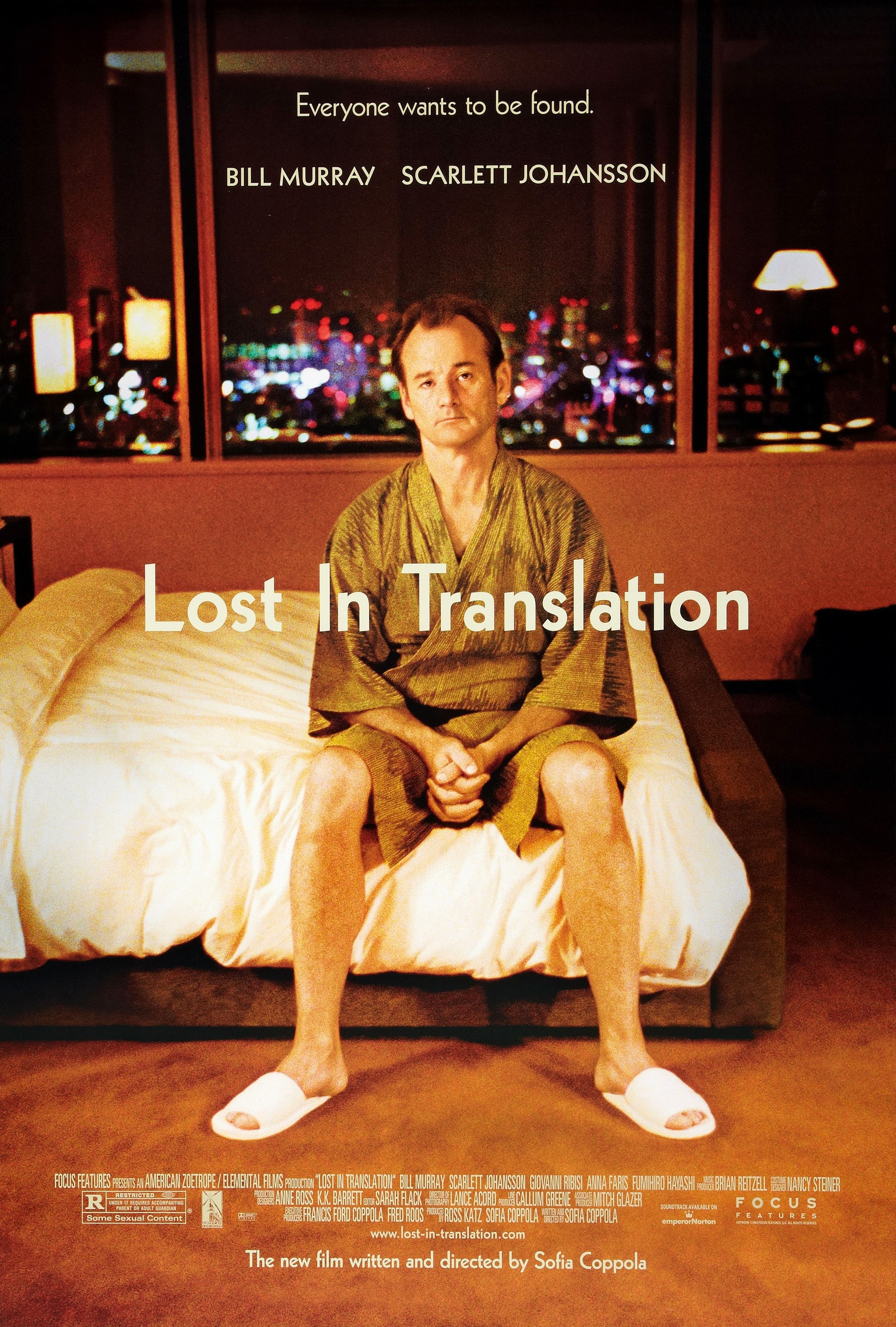

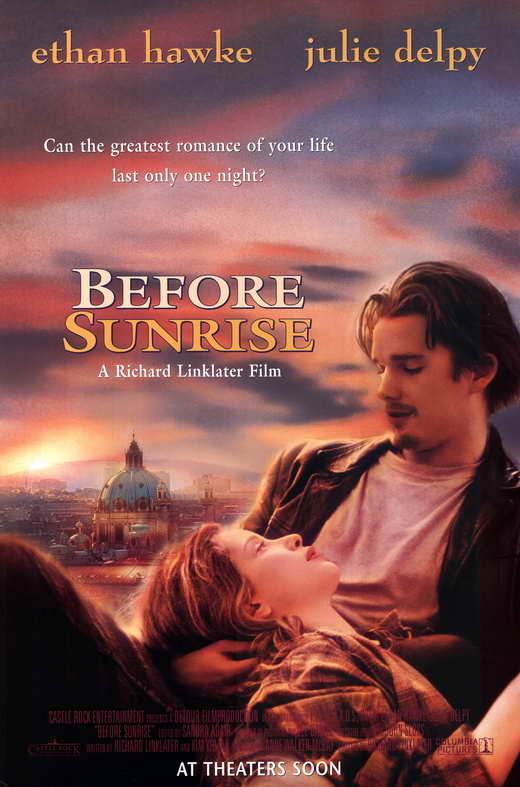

From here, you could imagine the major plot points extending through the rest of the film. Here, we have screenwriting 101, it's as simple as it gets and no one really needs to be told about it. This kind of plot is there to ensure some kind of movement. You also here this expressed as 'change', but plots don't always need much change as would be demonstrated by the likes of:

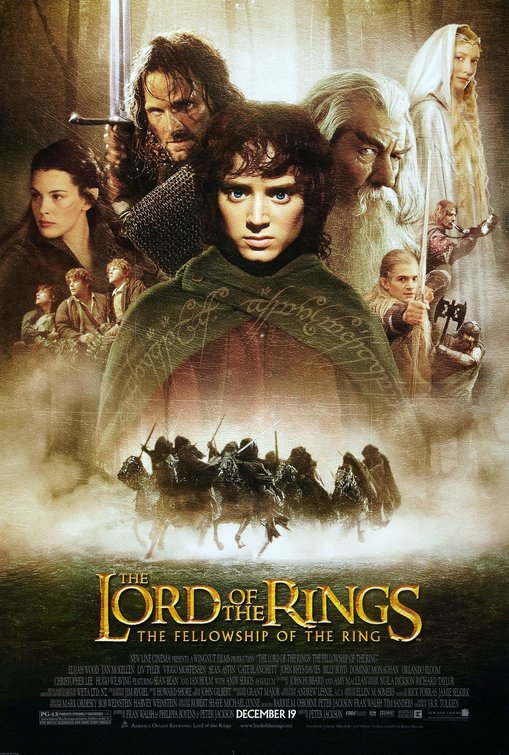

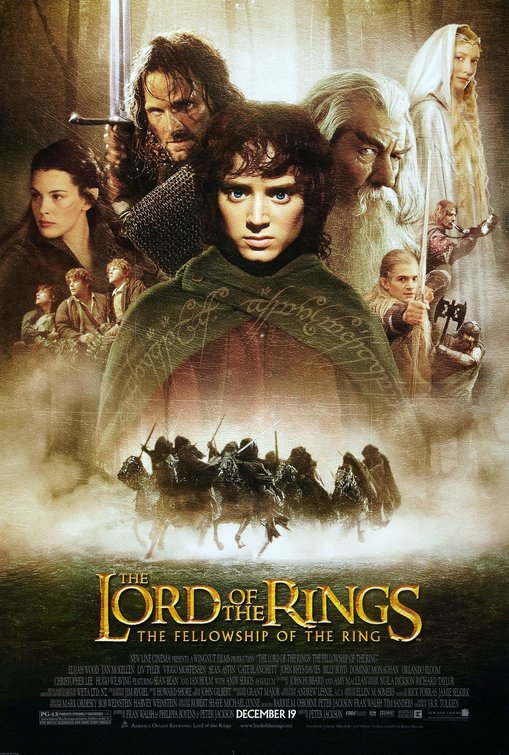

We'll to why these films work in a moment, but they firstly express that narratives don't need 'change', which implies a spatial movement or a large arcing plot demonstrated by epics such as...

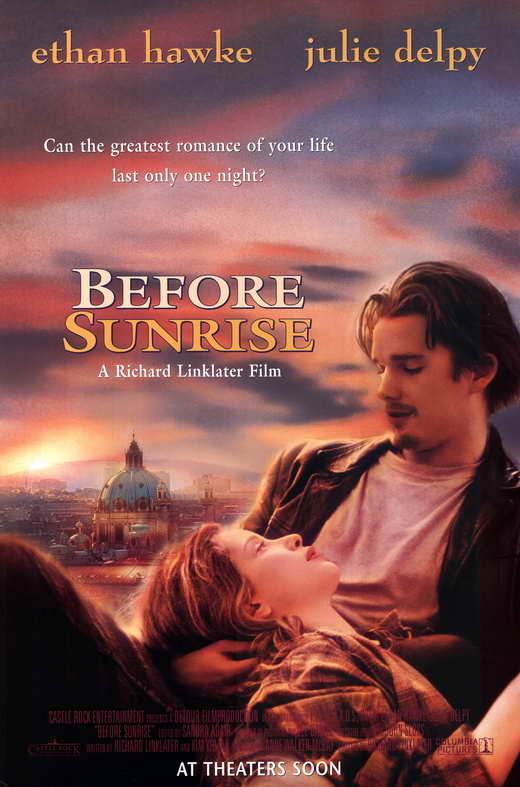

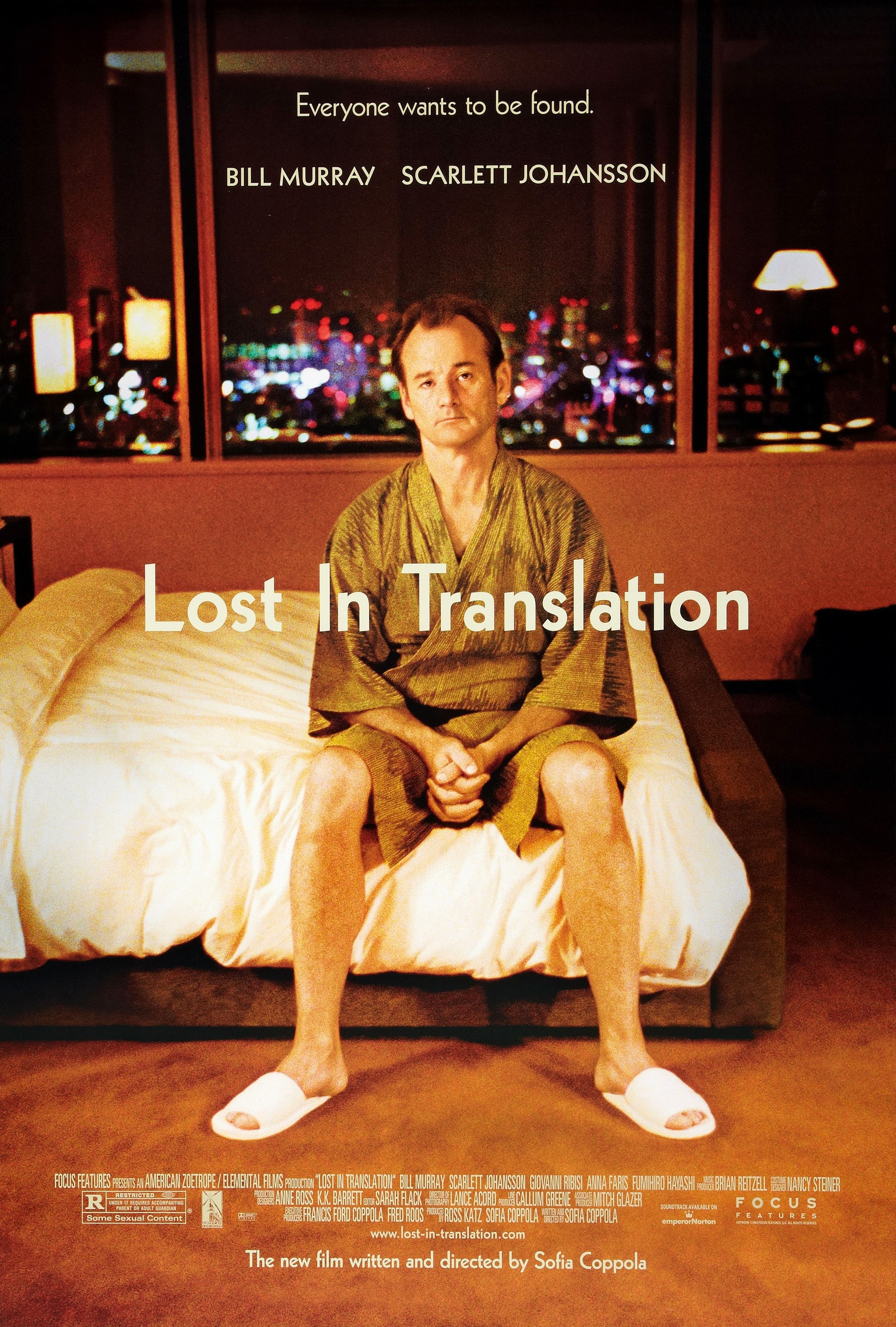

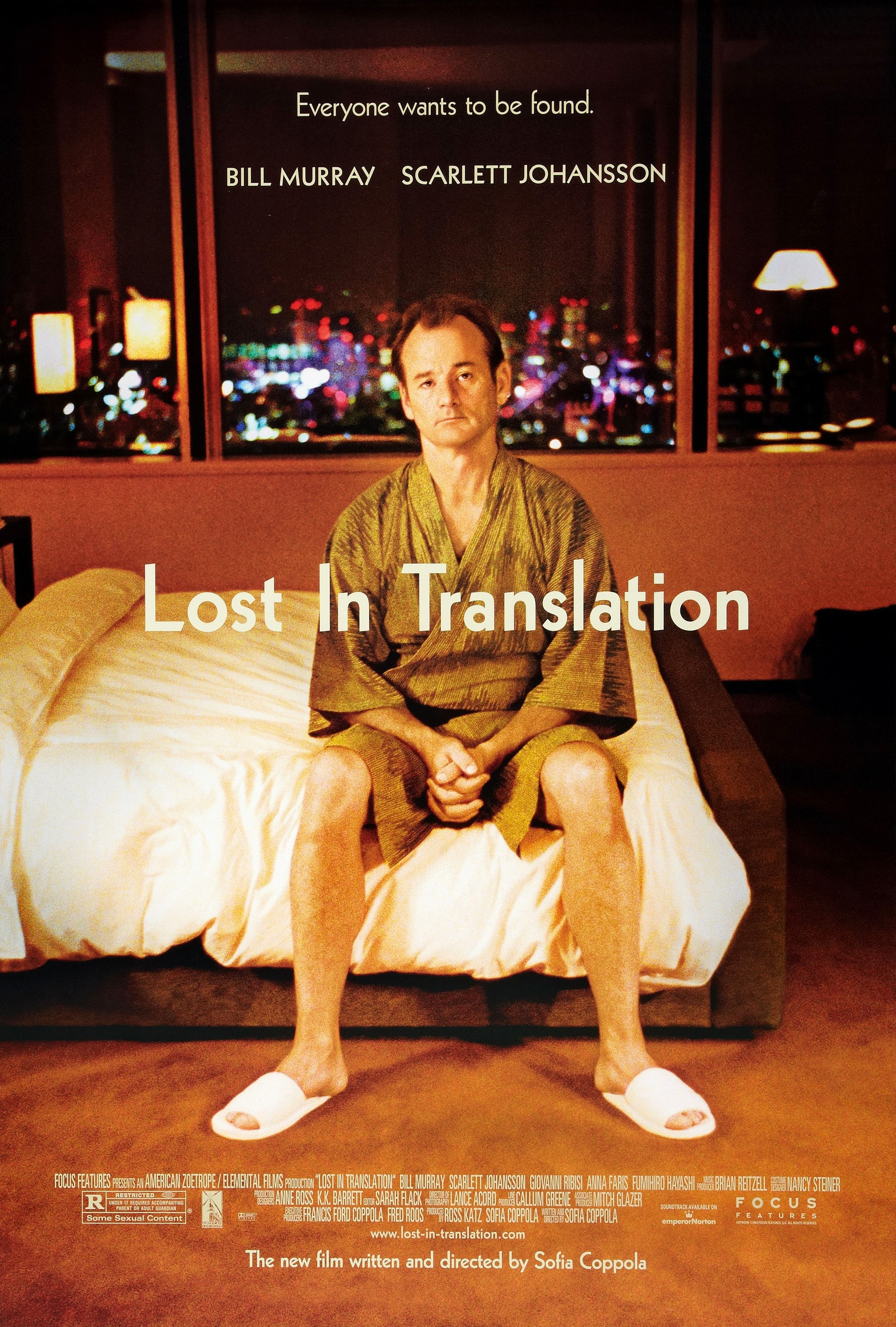

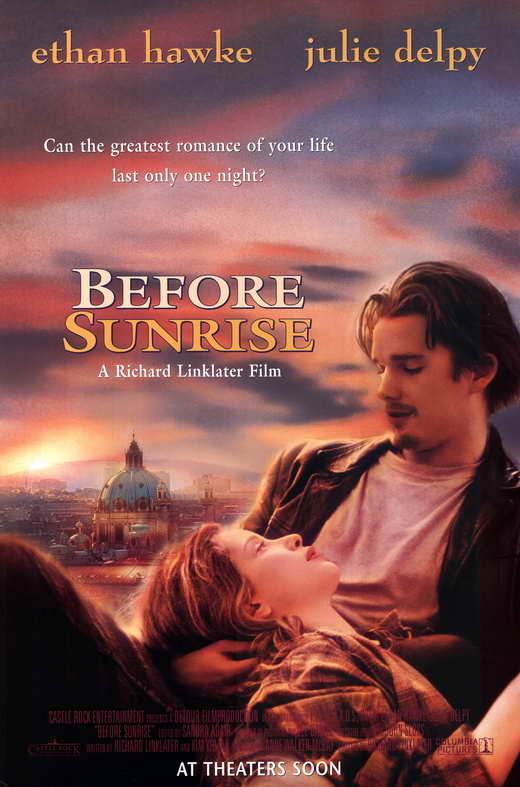

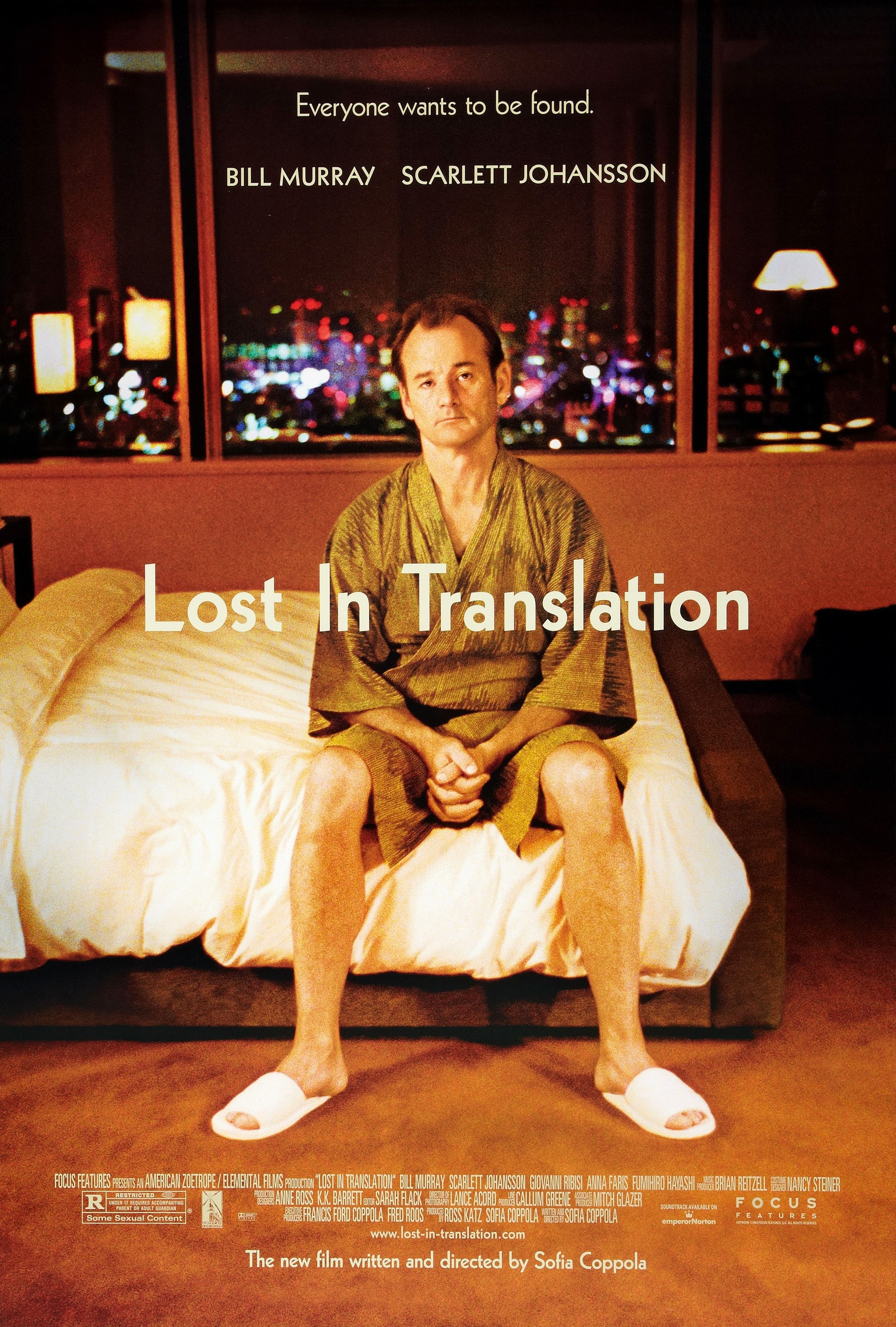

Plots of this type need to get you from A to B. They are completely dependent on external, physical conflict. If you look back to the first 4 plot points of Cinderella you see the major points of conflict. Firstly, there's Cinderella's past and how it relates to her current situation: a slave to her step mother. The second and third show the conflict between the animals and the cat - as well as between Cinderella and her 'family'. Lastly, we see the way out of the conflict (the Prince). However, in this we only find more conflict - and that's what the second and third act will echo until Cinderella overcomes all conflict. Seeing this, you can recognise that, like Clerks, Before Sunrise, The Shining and Lost In Translation, conflict can come in small doses, that it's not attached to different locations, and the expression of that physical conflict doesn't have to be war. Having said that, we move to the second type of plot.

The second kind of plot is a much harder concept to demonstrate on screen. It's the plot of your character arc, of internal conflict. We'll demonstrate again with the first act of Cinderella:

1. The emotional torment Cinderella has endured in her young life is exposited.

2. Cinderella as an adult demonstrates her emotional growth, her ability to carry on under duress as well as hold on to hopes and dreams.

3. Emotional stakes are added to the film by demonstrating the fear the mice have over Lucifer as well as the stress Cinderella is under because of how much of a bitch her stepmother is.

Now, I understand that all that I've just said is pretty redundant and circuitous because I've kind of explained why the imagery doesn't work for me already. However, I mean to pick up on a larger paradigm of films we get and films we don't get. The reasoning behind us not getting certain films is down to miscommunication. Beyond why or how this happens, I think there is something much more macro and micro-cosmically universal going on. By this, I mean, through something as conceptually banal as 'imagery', we see an existentially intimate and vast relationship between people and the world around them.

These images focus on string as a webbing that possibly trap a woman or couple. In such, I see the presentation of an image, of imagery, as the use of a physical presence to communicate an intangible being. We see the string as an attempt to talk about the intangible concept of the couple, their relationship, feelings and so on. (Though, I'm not too confident in this analysis of the film). Nonetheless, imagery is all about using the world around us to communicate how we (characters) perceive things. It's with this definition that we can see all the better the difference between Psycho and Eraserhead...

With Marion looking at the money we are seeing the intangible concept of her feelings articulating themselves - it's emoting/behaving/acting that tells us the story here. With Henry stood before The Lady In The Radiator, it's not enough that he seems scared, that The Lady seems sweet, that the actors underneath the characters are portraying emotions. Their physical presence isn't doing much of the talking - instead it's the film around them:

The same attempt is being made in Witch's Cradle - the attempt to communicate internal ideas of the characters through external and physical objects...

What inhibits this expression or communication between myself and this film just as it may you and Eraserhead (any abstract film you don't get) is the fact something is malfunctioning along this line of communication. It's either me, the image, or the character on the other end. What myself assuming that the film, the characters or imagery, are at fault says is that the filmmakers have failed to prove to me that they or they're characters exist. I know, existential, but let me clarify. The whole point of using physical things to talk about intangible ones is that the intangible ones can't speak for themselves. We'll hold onto the idea of Marion in Psycho to delve deeper:

Yes, this is a direct example of an expression of character, but, on a fundamental level isn't. We're being told of Marion's plans to run here - we're being told of her imagination. However, her imagination isn't physically telling us that its going to use this human body to take this paper and run away so that the brain it's attached to continues to pump out the good drugs: love, happiness, comfort. Such is obvious; we're not telepathic. Instead, humans are built to read facial expression and body language. And so, it's the image above that quite literally has the capacity to speak up to or more than 1000s of words. It's the physical presence of Janet Leigh as the middle-man that connects the lines between Marion Crane's imagination and ours. What's interesting is what this says about these images:

Deren, Duchamp and Lynch are in the business of employing new telephone operators to connect lines.

Instead of using actors, they use flowers, knives, string... weird, foetus things. It's the artistic exploration of imagery that is the human endeavour to better communicate. It can be in French, Latin, Spanish, on paper with words, on stone with hieroglyphs or on screens with emojis, but people constantly strive to say things in ways that better communicate their hidden internals - their mind hidden behind their eyes - to the internals trapped in other people.

And it's here where we come upon the crux of what imagery is. Abstract, simple, somewhere in between, all imagery is the endeavour to best say that we are alive, that we exist, that there is something going on in here. Imagery in film is just the attempt to speak in a unique language that hopefully communicates succinctly who we are and who characters are. Keeping this is mind, we have the tools to better tackle the concept in application. What's more, to the stand-still vacuum presented by you saying "I don't understand this film and I don't really want to" and someone else retorting, "You just don't get it", you can now just reply: "I just don't think the film exists". Sure, there's still an agreement on a disagreement to be had, but also a pretentious segue into a debate on the existential tangents of imagery. And if that keeps people talking, well, that's kind of the point, what we all seem to want: to keep yammering on about ourselves.

The Private Life Of A Cat - Personification

This is a simple yet awe-inspiring film. It takes a home-grown approach to the idea of a documentary and turns it into an almost fictional narrative. We see this in the use of POV, the intimacy of the shot types that always keep us close to the cats, but most importantly in their personification. Documentaries are quite obviously the documentation of real events, the goal is to portray literal happenings, not manipulate them. With the use of POV and the emotional telling of this story we are feeling the hands of the directors (Deren and Hammid). This manifests itself in the form of personification, in us seeing the animals as characters, as beings, through comparison to ourselves, somewhat understandable. This injects the fantasy into the narrative, slowly pushing it further from a 'documentary'. However, in saying such we enter a semantic debate. If you look to almost any documentary on animals you'll hear personifying terms, things such as 'he', 'she', names of the animals (not Buffalo or Lion, but Ben or Lenny), emotions of them, their internal intents or thoughts. This is all delivered in voice over by the likes of the legendary Attenborough and is there to turn what is often random pieces of footage into a cohesive story, into a captivating narrative with characters and emotions. This is the accepted format of modern documentaries and has been for a long time. However, I'd shy from calling them just that. To me, these are most coherently documentaries...

These films are about people, real events involving a skewed portrayal of a mundane reality by design. In other words, all of these films have an agenda, they mean to portray something from a predecided position or bias - especially the first two. However, because the subject of these documentaries focuses on the biases of Michael Moore, Herzog or Coppola, we are supposed to see the documentation of what is essentially their perspective. The reason why something like Frozen Planet or The Private Life Of A Cat cannot really be put into the same category as these films is that animals cannot project their own perspective by interacting with the camera of giving their own voice overs. This essentially means that there's a documentation of an external bias in these films, that the source of documented commentary has little validity as it doesn't portray exactly what it set out to do. However, this is where the semantic debate of what is and isn't a documentary becomes almost trivial: you can't document an animal's internal thoughts or emotions. This leaves filmmakers resulting to V.O and personification to sell the documentary. This, for me, isn't good enough reason to call the likes of this film or Frozen planet true documentaries. That's simply because they approach the narrative without a stated or explored philosophy of what animals are. This is what Grizzly Man, in part, does. It asks how different animals are from ourselves, if we should or can pass the 'Invisible Line' between ourselves as one species and them as another. If the likes of Frozen Planet explored this question, if it looked into the biology and psychology of these creatures before personifying them, then I believe we'd have a true documentary because there's an established bias or accounted perspective. As mentioned though, there's another distinguishing point of what is and isn't a documentary under the guise of form...

I love Man With A Movie Camera and bring it up almost every time I touch on documentaries, but I don't really see it as one. Man With A Movie Camera is just a film to me - a fictional one. Because of the film's form, its technical focus on direction, editing and camera operation, I see its crux in the manipulation of reality to convey a narrative point. The same can be said for The Private Life Of A Cat. This film is not about documenting how cats live, it touches upon foundational ideas of life - society and reproduction - and keeps its focus there. By using POV, tight framing and personification it means to have us think about ourselves, about existentially human concepts before a feline perspective. This is a crucial distinction in my opinion because it truly opens the cinematic gates. By assuming everything containing a camera on a real person is a documentary we wouldn't have fictional cinema. Moreover, we wouldn't just be calling all films documentaries, but we wouldn't have action, romance, fantasy and science fiction on screen as we would now. By assuming an approach to cinema that was dogmatically documentary-centric, filmmakers' fundamental question when approaching a script or premise would be: how do I make this real, how does this reflect reality? This means that verisimilitude, making things believable and real, would be the primary judgement of a film as good or bad. This would ruin cinema as we know it. We couldn't have a Hulk, Terminator or Godzilla. They would all be a ridiculous gimmick that'd make no sense under the laws of documentary - it'd be silly people using films to project childish imaginings, not comment on ourselves through entertaining bodies or forms (Hulk, Terminator, Godzilla). All films under the law of documentary - this really should be a sci-fi film about the first director audacious enough to make a blockbuster - I've said it here first, so if any of you wants to steal the idea, I want story credit, ok? Anyway, all films under the law of documentary would be strictly dramatic, would be at the most extreme, shitty reality TV.

Having recognised this hypothetically fundamental approach to film where we wouldn't see, let alone accept, actors as actors, as people pretending to be other people, we can now turn back to documentaries on animals. There's not really such a thing as animal actors - outside of reality TV (burn... I know). In all seriousness, there's no animal actors. We've had birds, apes and dogs that star in films, but that was a gimmick, that was a bit of fun or for the purpose of children's movies/programmes. What this says is that we kind of already live in the sci-fi Documentary Law world in respect to many 'documentaries'. The whole reason why the likes of Frozen Planet are boarder-line documentaries is that we find it quite difficult to bridge the gap between animals in respect to fiction and documentary cinema.

What we see here is the closest we get to using animals seriously in fictional film. What's interesting though is how quickly things turn childish and then complete shit. I've not see War Horse so I can't say anything about that, however, I don't really like any of these films. Some, such as Marley & Me are fun, but not really much more. What this says to me is two-fold; firstly, The Private Life Of A Cat is in fact quite a special film, and secondly, personification in film is a difficult thing to pull of.

We'll zoom in on the latter first. Personification is a hard thing to pull of for many reasons. The most obvious is that we don't understand the psychology of other species very well and that you should never work with animals (or kids - or reality TV stars - burn...). But, beyond physical application and filming, personification is difficult because its not too different from this...

Yes, you could say it's racist, insensitive, this that and the other, but, to me, this is first and foremost a terrible artistic attempt. It's a combination of bad writing, bad acting, bad make-up and direction. One day when we create chips that we can insert into our own and animal's heads as to talk to each other, they'll be looking at this...

... as the same thing as the Landlord from Breakfast at Tiffany's. All of this would be misrepresentation, oppressive, prejudice, and if you're laughing, plainly hateful. But, it's at this point I'd like to note, I don't like dogs or cats, I'm miserable and aren't drawn to this subject because I'm an animal lover, like to look at these pictures, think they're cute or whatever. Why'd I have to say that? I don't know, I'm miserable. Either way, the point is that in the same way you can 'white wash' human characters you can also 'human wash(???)' animal characters too. You can put onto bodies misrepresentational disguises to entertain no one but yourself. Do I think this is the end of the world and that we should all be calling PETA? No, not at all, I couldn't care less. The point being conveyed, however, is the need to personify dogs, horses and cats is one born out of a miscommunication.

Now, hopefully you've read the last posts (link here) because we're going to be picking up where the talk on imagery left off. Art is all about communicating, from our internal cages, from our minds trapped behind flesh, goop and blood, to others that we exist. Communication can be done through words, writing or art. In the same way these squiggles communicate my internal thoughts to you, so would a painting, dance or film. How successfully and poignantly a movie, performance or painting does this is the measurement of good art. Art is then there to find new way to communicate things with (hopefully) greater accuracy and weight about ourselves to other people. If you look at this concept under the idea of imagery, you could say that all images in a film, each and every frame, is a painting that has a thousand words. Now, the further implication of this is that everything in the frame is an expression of an artist. So, when we look at this...