Receptacle Series

Repulsion - Internality Complex

A young woman, Carole, is left home alone when her sister goes on holiday to face personal inner turmoil, realised.

This is an undeniable classic. Whether you want to call it a horror film or not, it has one of the eeriest atmospheres, some of the strongest sense of direction, pacing and surreal meaning in all of cinema. To get into this meaning, it's easiest to follow along with the narrative as this film is essentially a culmination of events and feelings that cause Carole to break down entirely. In other words, we, like the film, will build up to a climactic idea of why Carole is the way she is. This of course means SPOILERS. If you haven't seen this film, what's wrong with you? Go see it. If you have, well, let's get going. So, we'll start as the film does, with the beginning. The film opens with drums reminiscent of an old movie monster movie, something like King Kong, a simple BOM-BOM, BOM-BOM. This is layered over the crucial image of...

... Carole's eye. This isn't just a haunting image, but the key visual metaphor of the movie. This is all about bodies as a medium between which the outside world interacts with the inner one. Most poignantly, this is a film about how what Carole sees being irrevocably controlled and contorted by memory. With the added monster movie-esque sound track over this metaphor it's clear that something ominous lies within her, that something is going to break out. But, with a pull away, we realise that Carole is at work, and that she's a beautician. This is very interesting for quite a few reasons. Firstly, beauty is all about judgement, about looking at something that's probably imperfect and then trying to fix it. What this means is that Carole wipes mush and slathers paint on old people all day. This job seems to suite Carole as she's clearly very analytical. We later on find out that she has some form of OCD, OCPD or hypochondria. To be fixated with things being 'perfect' in this regard would allow her to fix things, paint nails, push back cuticles, present someone as she'd like to see them as a beautician. This would be a great job, if Carole didn't detest imperfections such as cracks (a very important image we'll come back to later). All this means that she gets to soothe her OCD, but must endure a hypochondriac's nightmare of being around uncleanliness and people. The most important thing about Carole's work though are the people. Most descriptions of this film will describe Carole as androphobic which means she's afraid of men. This is true to a certain extent, but doesn't make complete sense. She's repelled by men as the title suggests, but still has a muted fascination or attraction. This means that being in the beauty parlor all day ensure that she's constantly around women, so she doesn't have to endure the stress of being around men. However, there's a but. And this 'but' is that she makes herself and others beautiful, but that inevitably draws the attention of men. This is her opening and most enduring conflict. It's the image of the eye and the implimence of her work place. She walks a thin line between comfort, discomfort and horror with her convoluted relationship with men and cleanliness. This keeps her in a place that allows her to make the unclean and unkempt better and keeps her away from men, but only momentarily. It's this conflict that stagnates Carole's life. This is why she's often in a trance around others. She's both physically and mentally stuck between the outside world and internal one. Her body and mind seem to be working against her.

It's taking these images at hand that we can move on to a key idea of the film: food. Food is quite simply a tangible object that traverses the distance between the outside and inside worlds of a person (literally). The major importance of food though is that it's a sensory extreme in the opposite direction to eye sight. Taste is the last sensory barrier between you and your environment. You can hear and see things coming from miles away. You can smell things from quite the distance too. These are peripheral senses and so primary, but not really personal. If we stay with smell we can see why. The closer things get, the stronger their smell becomes. This is why it's an important social cue. If you stink, people will keep their distance. But, if you smell nice, you draw people in. Now, with the jump to touch things get even more personal. There are extremely strict social rules for touching. You may shake someone's hand, possibly hug them, possibly kiss them on the cheek if you're not well acquainted, but are meeting (say for the first time). Other than that, physical contact is quite rare between strangers in most places. We save that for friends and loved ones. Take this a step further and you come to the sense of taste, and the mouth. Yeah, this is where things get awkward. Putting your mouth on people is not something we're very adventurous about, especially beyond the lips. This all makes clear the stark difference, in social terms, between the eyes and mouth. Eyes are, in a certain sense, for everyone. The mouth, very few. It's in this regard that you can see food and eating as a strangely sensual thing. Especially with others. Maybe it gives reason as to why cooking for others, giving them food or even going to restaurants together is something inherent to dating. Nonetheless, when you apply this to Repulsion, Carole and this image...

... you get a clear juxtaposition with the previous eye. It's with this that you can recognise Carole's true repulsion is not exactly men, but things getting inside her. As awkward as it sounds, it's true. This will become all the clearer later on. But, before getting to that, it's best we move with the narrative and welcome a few character introductions.

It's with Carole's sister, Helen, that we can dive deeper into social behaviours as touched on before. Carole's sister is the only person she feels comfortable with, she's the only family she seems to have. Combine this with Carole's job, the fact that she only seems kind of comfortable around women, but then throw a boyfriend into the mix and you're bound to run into conflict. Primarily, the sister and boyfriend relationship is an interaction for the film that is in spite of Carole. The boyfriend not only takes Helen away from her, but does so in the most repellent way (to Carole). The question then raised here is of why Carole doesn't just live on her own. The answer is never made explicit, but is implied to be another contradiction of her character. She can't stand people, but needs affection - something only people can supply. It's for this reason that we can recognise that Carole isn't androphobic - she entertains the idea of a boyfriend. Colin and his intentions with Carole are another relationship in spite of her. (I think it's fair to assume all are). But, we can't get into this just yet. To wrap up the film's introduction, it's best to bring together what we've been over with the rabbit. Helen prepares to cook this for herself, boyfriend and sister. This is a social scene that, despite being uncomfortable for Carole, is bearable. However, the boyfriend negates this by taking Helen out himself. Moreover, he marks his place in her home with the razor and tooth brush (in Carole's cup - another reference to the mouth). And to round this off, he sleeps with Helen - quite audibly so. This is everything Carole cannot take, but it's all rounded off with a nice euphemism: 'the minister of health found eels coming from his sink'. A fake news item with sexual implimence that also makes you cringe in disgust. I mean...

The last thing to touch on before moving into the film's second act is the church bells that ring night and day. The nuns that live across the way from Carole are an image of abstinence and purity. We can assume that through Carole's eyes living with only women and not having to interact with many people would be more than satisfactory. The bells are then a reminder of this religious idea of purity and also marriage. The latter is important as Helen's boyfriend is cheating on his wife to be with her. This would sully Carole's view of her, again convoluting the relationship. Now, I can find no reason as to why the nuns or campanologists of the church would ring the bell at midnight. The only grounded reason I could find through a bit of Googling is that they might be practicing. Beyond tangible reasoning, the bells ring at night as a reminder to Carole, Helen and Michael (the boyfriend) that what is going on is wrong. But, again, this is made fun of with Michael suggesting he nuns having a party when the bell is ringing at night. This lets us see a pattern. All of Carole's major conflicts are revised through comedic quips that cite an 'us vs them' idea. It's the extramarital relationship in face of the church, Carole's sexuality in face of her apprehension toward men and Carole's anti-social behaviors and OCPD in face of the need for affection. What has been resoundingly set up here is an external world vs an internal world. Specifically, from Carole's perspective we're talking about things trying to get inside her. trying to pass a personal barrier in metaphorical and physical terms. It's through the first act that we can clearly see this set up to her characters. We understand that she perceives many external forces from food to customers to church bells as a threat.

It should now be transparent what sets Carole into a downward spiral and why. It's the old woman in the cosmetics chair talking to Carole's friend about men.To paraphrase, she says that they are like children. You are to treat them as if you don't give a damn about them as that's what they want. They want to be spanked but then given sweets. This is a culmination of Carole's conflicts considering she just refused to kiss Colin the previous day. She thinks he sees her as playing hard to get - and that that's what he wants. There seems to be no way she can communicate her actual apprehension without leading him on. With her sister gone she is also alone. She's also with an old crone with shit on her face, her lips specifically, who also wants something to eat.

This is freaking Carole the fuck out! Men, food, unsanitary mouths, control is everything Carole can't deal with. And so, she retreats. She goes home, welcoming act 2.

Carol comes home to three things. There's the money, the rabbit and the ringing phone. The money is representative of financial security, of Carole's home with her sister essentially. The rabbit is a symbol of her relationship (and it's rotting). And the phone, yeah, I know, a trope...

... but why? Why is the phone the scariest thing to ring at night, when it's dark and you're alone? Well, there's two things. The fist comes back to senses. If sounds are peripheral sensual cues, then they imply something is coming. And what device better translate that idea than a phone? It takes a distant voice and puts it right up to your ear, leaving you completely unaware as to where it originates from. But, more than this, the phone is a social cue. For Carole it would imply a social exchange is about to be had, whether it's with Colin, the apartment manager, whoever, she probably doesn't look forward to it. This is all payed off when the interaction with the apartment manager does occur - and it doesn't go well.

Now, returning to the rabbit, it's important to echo a previous comment in reference to the outbreak of myxomatosis, as disease that is highly infectious and wiped out approximately 99% of the rabbits in England in the 1950s. Myxomatosis isn't a threat to humans, but serves as a nice metaphor toward the rabbit as a symbol of social interaction (a meal). Carole probably questions if it's diseased, refuses to cook it, but in doing so lets it rot. The same may be said for how she treats her friends and possible boyfriend. She keeps them distant, running the risk of sullying the relationship - and all because she falsely assumed it was infectious. Her conflict is thus a problem of self, of how she perceives the world and her self. In other words:

She assumes that the world around her is twisted, but it turns out that it's really her view of it that is distorted.

It's having gone over all of this that we return to the image of the nuns after Carole smells Michael's vest. This is another reference to both men and senses in juxtaposition to purity. This is rounded off with the image of the old woman across the way with her dog. This is an idea of loneliness and isolation that tempts Carole, but, as smelling Michael's vest implies, Carole's curiosity is growing. And it's for that reason that the scene ends with a crack forming in the wall. What this makes clear is that we are moving int o a different narrative realm. The house is now explicitly representative of Carole herself. It's sanctity becomes her sanctity, it's destruction becomes her destruction. The effects of the old woman's yammerings on Carole are the triggering of multiple fears and indulgences. She is becoming more curious of men as her fear of what they can do intensifies. Moreover, the idea of loneliness, purity through religion and cleanliness go awry. And this is all because Carole's mind is being laced over reality, blinding her to rationality.

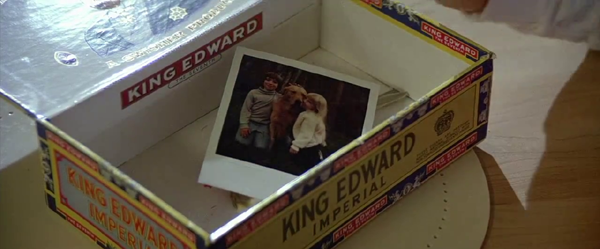

Now, it's after picking apart the house itself that we'll be able too fast track through the film. What we simply have to realise is the importance of the numerous trinkets lining the shelves and cupboards of the house. They are seemingly all memorabilia from her childhood. The most important of these items would be the picture:

This is the crux of the film. It's the family Carole has left behind. What we end on is a zoom in...

... that clearly shows some kind of fear or disdain in Carole directed toward what we can assume to be her father. This is implied to be the source of all her fear of men. But, this is not what the final image, the last zoom in captures. We can understand this with the opening 30 mins alone. It's over the course of the remaining narrative that we see the complexity of Carole's condition. This then leaves two things to break down. There's Carole's violent fantasies and then there's the murders. These are intrinsically linked as reactions to one another that call back to the catalysing statement of control given by...

In short, the man that attacks her at night is Carole allowing someone to take complete control and the two murders are her reclaiming that control. She denies sexual advances and responds with violence. Before getting into this, this idea is probably the film's greatest critique. It paints female sexuality as an insistent need to be dominated, a demonised and scary concept even to the woman herself. There are more relevant critiques such as the sounds design (especially dialogue) but we'll stick with this one. This critique is connected to the fact that a man made this film, and that that man is Roman Polanski. So, yeah. But, looking beyond that, I would say that the poignancy of this film comes not with seeing Carole as a woman, as all women, but as a hyperbolised character who cannot get a grip on her perception of the external world in respect to self. Seeing her as this archetypal hypochondriac brings about the core philosophy of the film. It's all about the inner-self being a product of memory and the body being a protective bubble. Again, internal worlds and external worlds. You see this realised best with the murders and the contradictions inherent within them. The first with Colin being left in the bath is clear. It's the repugnancy of men (in Carole's perception) meeting an idea of cleanliness. This scene is supposed to be Collin's chance to be the hero. Something equivalent to the end of Hitch, or any romantic comedy where the guy just won't give up.

This doesn't work with Carole though because she's dealing with the power balance of a relationship. As is implied with the final image, Carole may be the victim of sexual abuse - and as a child. This would seriously convolute the love of a father with, dominance, sexuality and confusion. This gives reason for this:

She has no healthy idea of love and affection. Her killing Micheal is an attempt towards both ending what she feels is an inherently violent act, but also wash her hands (literally) with him. With the murder of the apartment manager, we get a call back to the very beginning with Michael's straight razor. She uses a symbol of external maintenance (link to her being a beautician) an image bound to men and uses it to both destroy a life and save herself. The contradiction in this is bound to the end with Michael carrying Carole out of the home - an apparent hero. This is all in emphasis of Carole's distorted image of the world. It's hard to say if Michael is a nice guy in this film, but maybe he's the only person Helen can be with. If she sustained any abuse like Carole, or experienced a family breaking up, it gives reasoning as to why she'd only find comfort in a destructive relationship.

The core takeaway from the surreal sequences is that the film eventually flips on itself. Not only does Carole withdraw completely from socialising with women, not only does she, as a hypochondriac, end up living in her own filth, but her internal world is put external. The house becomes her anxieties. It cracks, hands break through the walls, it's never a safe place, somewhere men are always trying to invade, church bells ringing on the outside, help too distant. And of course memory is framed for all to see. This leaves Carole a shell of a person, a zombie. All that's left to identify her character is this single image:

A memory. She struggles with so much over the course of the film and for untold reasons. We can infer that food represents social acts, that she is afraid of men, that she has OCD, but for what purpose? What is the message of the film under these circumstances? It hasn't got one, nothing with concrete evidence. The meaning of this film all comes down to an inherently human idea of self. Who are we, but the genes that organised our bodies, the experiences that molded our minds? If we are a product of the external world, of external forces, why are we almost never completely understood by it, by the world around us? We a product of extremities but are neglected by them. left trapped in a cage of self. And that's it, we are trapped. We are vessels of memory, forced to behave by our coded biases, the only sense that manages the internal and external, voiceless...

... perception an idea never truly under our control.

All in all, Repulsion is a film about insurmountable conflicts that drill away inside us. It's about a sensory disconnect. It gives us so much that means nothing without truly walking in Carole's shoes, without truly knowing her memories. Something we never get to do, and something impossible to do in life.

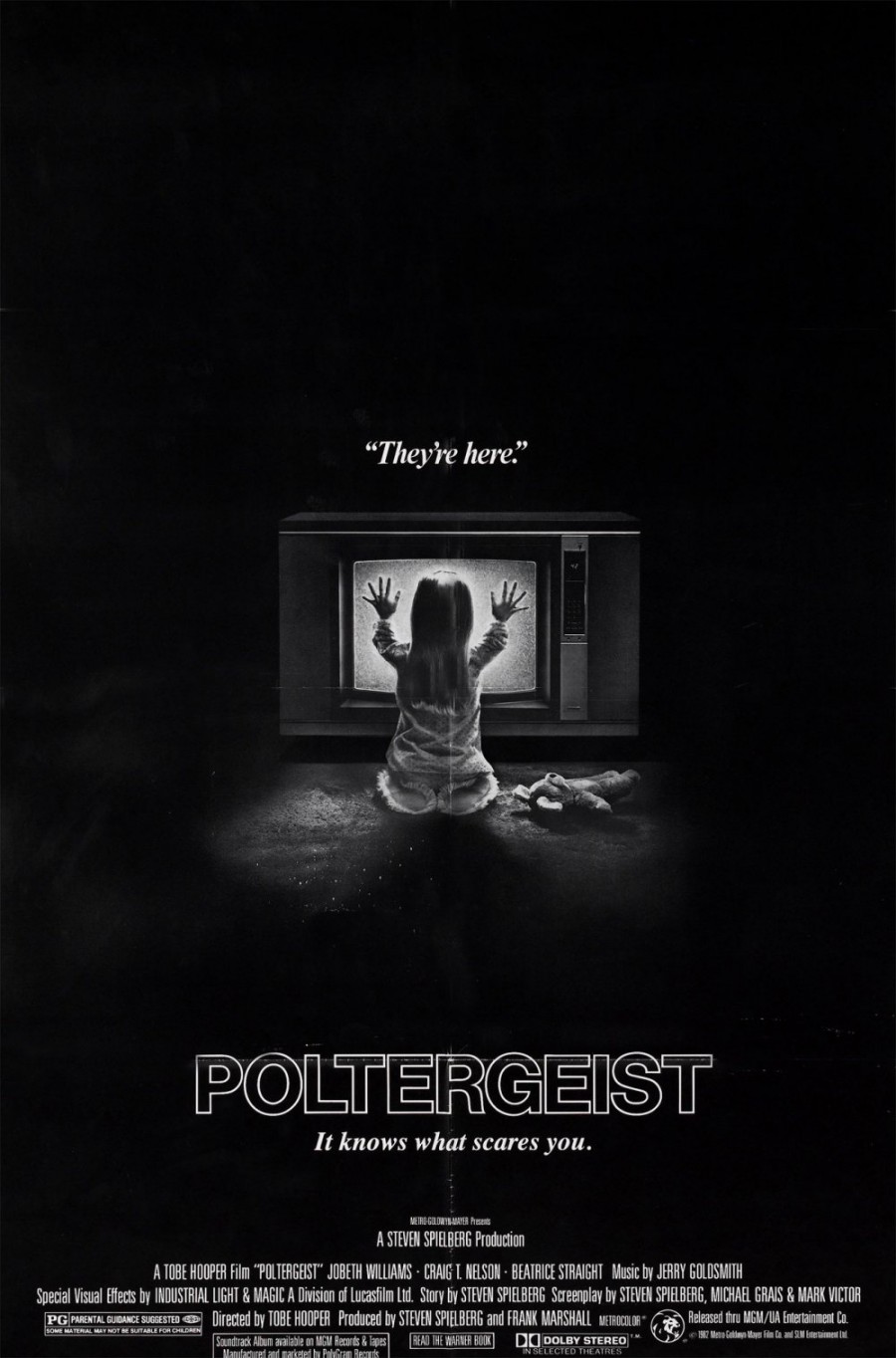

Poltergeist - The T.V People Are Coming For Your Kids!

Ghosts reach out to a family through their television set, eventually ensnaring one of their children.

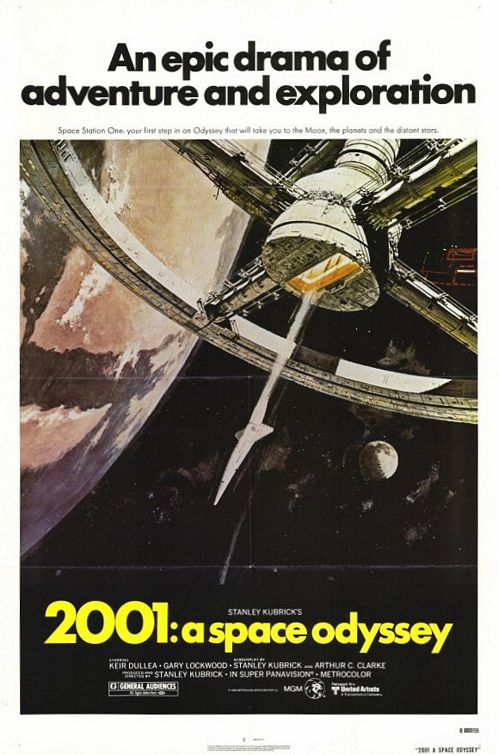

This is one of my favourite horror films of all time. Not only is it a perfect narrative with rich subtext, but it has great characterisation, pacing and is heartwarmingly comedic. That's a strange thing to say about a horror film, but it's true. The best way to describe this film is to say it's a family horror movie. It has the veneer of an Exorcist, The Shining or even more recent films such as the Conjuring or Paranormal Activity, but the heart of something like E.T, Hook or Close Encounters. And that's more than understandable because Spielberg of course produced this film, and it's in no way surprising that the man who made Jaws had something to do with this. But, to take a step back a moment, it's quite obvious that this film is a heavy influence on the cinema of today. (Again, Spielberg and Jaws anyone?). It perfectly set the tone for the current state of horror. What's fashionable in horror today is the paranormal.

There's a tonne more I, and I'm sure you, can mention here, but the link between these films and Poltergeist isn't simply ghosts. Ghosts are popular because they allow cheap filmmaking. There isn't a monster you have design, build, create on a computer. But, more than this, they allow two things. They allow deep commentary and great characterisation. Mama is an ok example of the former with a narrative around memory and death being constructed to comment on ownership and children. The The Babadook, however, is a brilliant example of commentary - something I'll have to talk about sometime soon. As for characterisation... well... you don't get many horror films with good characterisation. Nonetheless, you can see a half-assed attempted of this with Paranormal Activity. The formula and emotional structuring of the films in the series mimics that seen in Poltergeist. They start with meeting the family, trying to be relatable, implying strange happenings that escalate, often dissipating before rising for a final act. This is a general formula of many genre films though. Where we see the specific influence of Poltergeist is through the emotional structuring. It's the use of families and children in horror films. Family is a huge theme in almost all of Spielberg's films. This is where the root of his comedy is found and is where the film's heart lies. This is what Kubrick couldn't do with The Shining, just like Friedkin couldn't with The Exorcist, Carpenter with Halloween. However, horror films use family, or they use teens to suggest fragility (not weakness, but something to be lost - stakes) and a sense of identification through characterisation. Poltergeist is a perfect example of how to do this. It doesn't have the atmosphere or tension of any films just mentioned, but because the characters are all so strong it doesn't really need to. We care enough about them to have even minimal danger naturally mushroom into tension. This is why Poltergeist is not only one of my favourite films, but an important horror, if not directly to the genre, definitely to anyone watching movies wanting to learning something. It teaches us all a way of having art also be something entertaining, emotionally investing. And I think that's what film is about - and what makes cinema the greatest and most accessible art form. It's entertainment coupled with higher art.

So, whilst what is entertaining about this film is obvious to anyone who's seen it, the 'higher art', its intricacies, subtext, metaphors and so on present within, can go unnoticed. To get started, this film is about parental responsibility in respect to T.V. It's core philosophy comes with an idea of intelligence and imagination. Before getting into the film's narrative, it's important to pick out peripheral writers' devices. These are elements of a film meant to explain or present a narrative in a way that is somewhat tangential to its core. If you look at The Matrix, a film about free will, destiny and technology, you can exemplify this type of element best with the romance. Yes, there is some relevancy to Trinity loving Neo, with emotions and blah-blah-blah giving reason for free will, but, it's just another one of these moves:

Cute, aphoristic, but, meh. The same kinda goes for the action in The Matrix. It's just not really necessary to discussing the core themes, but, at the same, not damaging at all to the film itself. With Poltergeist these elements are in the Indian burial ground jargon and ghost hunting. Both are a trope of the film, a way of socially affirming moral ideas tantamount to love in Interstellar. With the Indian burial grounds, it's simply saying: desecrating graves is bad, don't do it. But, not an awful lot more than that. There is a smidgen of something more though, and it's a reference with...

... no, not just smoking... ahem... plants, but ancient wisdom or simply the past. This is a segue into a core idea of the film. However, because what's the fun in writing a fluid essay? A quick interjection. This box:

And the one in Diane's hands...

... quite similar, no? They're not the same one, but possibly had the same use. Why this is relevant comes to the scene where Carol's bird dies and she says the box smells bad ("Tweety doesn't like that smell, put a flower with 'em"). Maybe it still smells of weed??? Which is a underhand joke, but quite brilliant. This plays into something we can come to later, but, back on track we get. Ancient wisdom and ancient burial grounds. It's implied that the ghosts attack the Freeling household because it's situated on a burial ground. That's our tangible, easy-fix way into showing freaky things, real skeletons and paranormal terror. But, juxtapose this with the fact that they come out of the T.V and you get a lot of questions you can only grip with metaphorical analysis. Paranormal electrical excitations and different spheres of consciousness only perceivable through gadgets, wires and meters is not at all scientific, leaving the insinuation that T.V could be capable of being a portal of sorts as nothing more than fantasy and a writers' convenience. However, take a step back and juxtapose the new with the old, modern technology with ancient custom, and you quite simply get an allegorical means of reflecting on the society of today. The opening scene makes this most clear. We start with the American national anthem, symbols of national heroism, pride and honour and then Steve passed out in his armchair. The American dream, no? Further this with the football game on T.V and the anarchy around that, and, yeah, American dream.

This all means that the shown attitude towards T.V aren't really the best human attributes. We like (we liked) to sit in front of a box and bathe in mediocre and meaningless entertainment for no other reason than to fill time. The obvious question to the zombified family, programmed by television, to the slob binge watching all the Netflix, just all of it, is: is there not something better you could be doing? The answer is yes. Of course. This is more important with kids. Playing outside, getting exercise, learning about the world and so on are all things you don't really do that well sat in front of T.V. The progression of technology has undeniably made us all smarter, but how much can you really learn from a late night show, Jimmy Fallon interviewing the cast of The Avengers? Ehhh... not much. T.V is primarily about consumption. Yes, you can learn the fundamentals of baking, how various points systems work, a plethora off oddly specific factoids from T.V, but we learn these things almost as a side-effect of waiting for a lava cake to ooze, that 17th tier to topple, a car to crash, a guy break a leg, someone to die, develop brain damage, points be racked up, a geek say smart things you can't fathom.

The relevancy of this to Poltergeist is quite simple. Parents and teachers should teach children, not T.V. Now, bring back the weed. No, I haven't got something incredibly profound to say, but this...

... isn't a very mature image. The parents, whilst not very naive, aren't incredibly grown up in this film. We can come back to the dead bird to see this. Just before she's caught dangling the dead canary over the toilet bowl Diane asks why it couldn't have died during a school day. This is obviously so she wouldn't have to have the discussion on death with her kid. This is understandable as she is young, and death is a tough subject, but the implimence is that Diane would prefer Carol live in an imaginary world, one where you make up the rules, where death isn't always a thing, let alone something that matters that much. This kind of sounds like the world of T.V, no? You could say I'm reaching here, but is death and television not something that has already been established as the two driving forces of the film? The metaphor of ghosts coming out of the T.V can then be translated to the idea that television does feed the mind, not healthy stuff, junk food. It only does this however, because it wants to consume us. The media industry as a whole is much like a farmer, us a bunch of pigs or chickens. It feeds us and feeds us and feeds us, then takes us for all we've got in the slaughter house. The thing is though, the slaughter house is merely the monthly cable bill. Consumerism begets consumerism - it's the capitalist cycle we live in. The only way out of this is to turn off the T.V, get rid of the Netflix account, throw it all out of you must...

... and live with the truth, in the real world for just a little while. This is why death and family are so important to this film's narrative message. It's essentially all about a family growing together. Not only do the parents mature, but so do the children. And that there is the film's end taken care of, it's not just a lasting joke, but the lesson given. How this message is translated though is very important - and is done in two simple ways. Staying with death and ghosts, both light and wind are used to metaphorically discuss character growth. It's the white light that represents both death and T.V in this film which makes the bird's passing all the more poignant. Despite almost immediately asking for a goldfish after the 'service' Carol might have been left with an existential question of life and her inevitable end. This could mark her journey toward adulthood. The other children alike are on this journey too with the Dana being on the phone all time, possibly to boyfriends. and Robbie trying to get over personal fears of the dark and freaky toys. All children are in pivotal stages of their lives leaving Diane and Steve with a huge weight on their shoulders. They don't want to lose their children to the television set. Essentially, they don't want T.V to take over their jobs as parents. So, light is many things in this regard, but it's primarily death and knowledge. Death is a narrative preset that, as said, allows us to have ghosts and skeletons. But, enlightenment is the crux of this film. It all comes down to a minute event of a dead pet being buried in an ex-pot-box. It's surreal, quite funny, but that's the core physical conflict of this film. So, with the two parents trying to steer their children away from the light at the end of the tunnel that is T.V, a cold wind blows. Wind of course represents change, giving solid evidence toward this film being about maturity, turning this iconic scene...

... into an image of the house enduring a storm of adolescence, puberty and parental anxiety. Wind, light and death and that's the film in a nutshell. There's more details to be found in the film though, but I'll leave them up to you. The main takeaway in the end though has got to be that this isn't a film completely against media, T.V and the modern way of living.

This all comes back to the very top of the essay and why this is a great film. Yes, it's entertaining, but it also has something to say in an intellectual and interesting way. In this respect, the film can't be condemning media, T.V and even cinema completely because it understands the importance of entertainment. Just like with film, learning shouldn't be a task, it should be fun. The same goes for parenting and life. Moderation is key. It's not letting T.V consume you, not letting the intellectual side of media be a by-product of the glam, absurdity, sex and violence. Let it consume you and you just might end up tearing yourself apart...

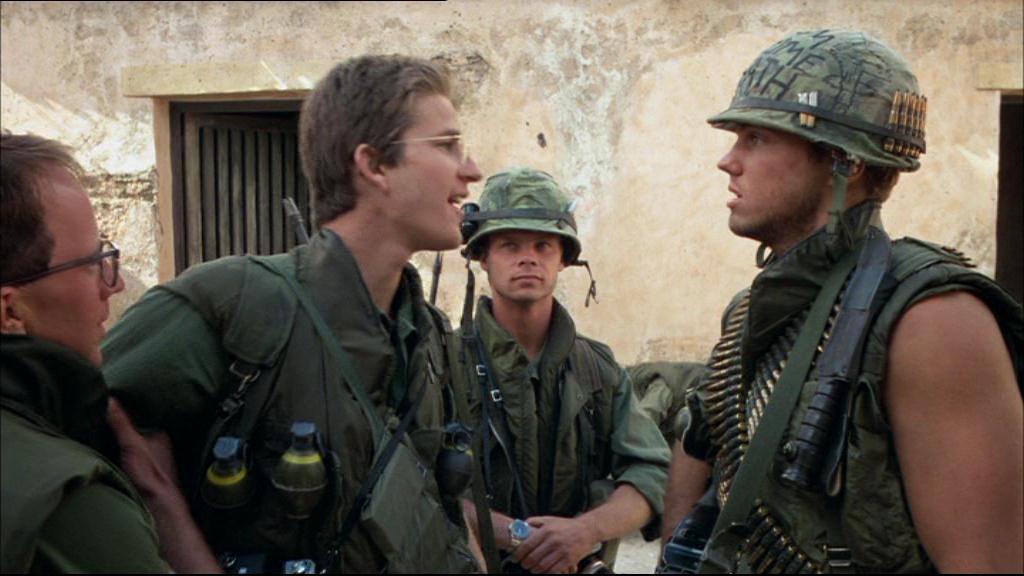

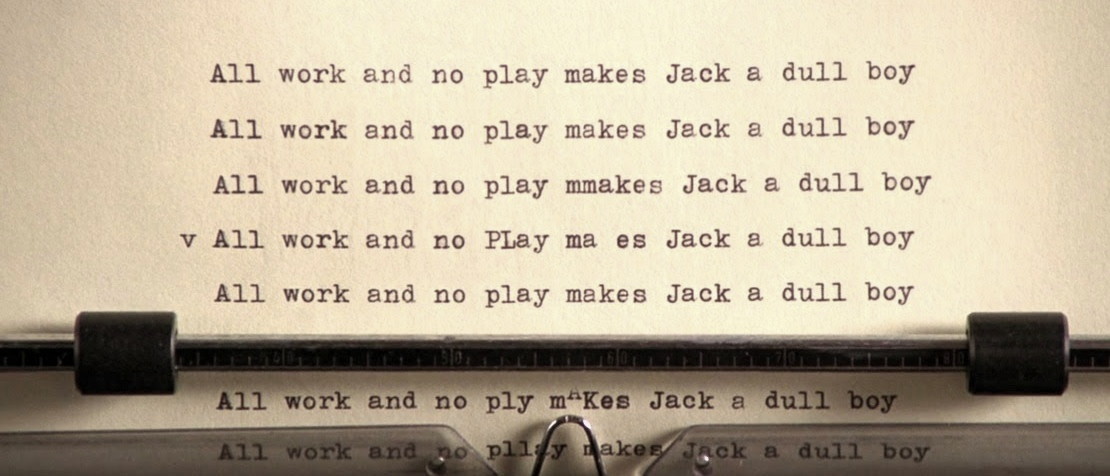

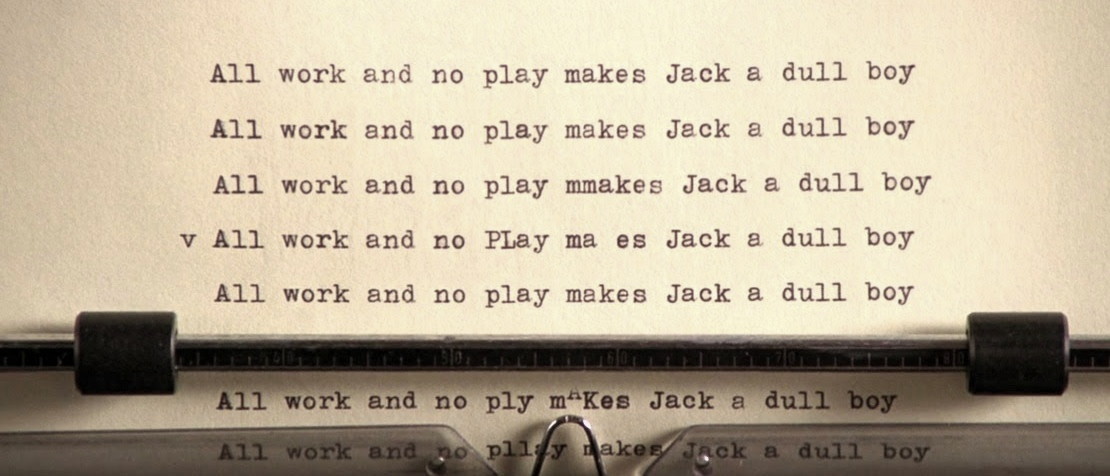

Full Metal Jacket - The Jungian Thing

A story in two parts, following Private Joker Davis through basic training into the Vietnam war.

There's many ways to watch this film, and dependant on the looking glass you choose, this film can be many things. If you want to see a war film, well, you're not going to really get one with Full Metal Jacket. The first 40 mins will be thrilling and then with the second half there will be a tonal drop off where the pacing goes a little awry and the film loses its gravitas. On the other hand, if you choose to see this film as a soldier's story, not a strict war film, then it becomes something a lot more. Upon release this film was compared to the likes of Apocalypse Now and Platoon - and critically didn't fair that well all across the board. That's because these are two immense war films. Apocalypse Now has an expanse, it's a thematic sound-stage that amplifies character struggles and internal conflicts through action. (Click here for more on it). Platoon on the other hand is all about the experience of war. It puts you in the shit and tears you apart with the struggles of its characters. Full Metal Jacket distinguishes itself from these two behemoths by not playing them at their own game. It takes one step further into the soul of the soldier. These films really support each other when you see them like this. Apocalypse Now is about a wider philosophy of humanity, Platoon is about the emotions of a soldier and his interactions with war, leaving Full Metal Jacket to be about an acute philosophy of self under the pressure of that wider idea of humanity. So, to get into this philosophical milieu we're going to need to cover a bit of psychodynamic psychology. As the title suggests we'll be looking at Jungian terminology here. Don't worry, there's no need to get too deep into things. Like Freud, Jung's psychological theory is very philosophical, meaning, not very scientific. But, to dismiss both works on the grounds that they're unscientific would be wrong as they have clear benefits and uses. This is hopefully what we'll find out with Full Metal Jacket. Psychodynamics gives people tools of assessment, and the two tools Jung supplies with his all important 'thing' is all to do with the duality of man. This means that there's two sides to us. There's the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious. Freudian theory suggests that people's minds are comprised of things we do control and can monitor and things we can't. This is quite simply the conscious and unconscious. Jung makes the further distinction to explain why we do irrational things. We do them for ourselves, for personal gain, or we do things for others, for the group. Furthermore, there's things unique to us personally and there's things we all do - all unconsciously. Taking this idea into Full Metal Jacket is the best way to watch this film, not really as a movie but an art piece, and that's what we're going to do now.

The easiest way to then do this is to walk through the film. So, it's the beginning we start with Johnnie Wright's Hello Vietnam. It's this song alone that serves as the only true and traditional character building in this film. It suggests that characters have a past, that they are leaving loved ones behind for obligation. The lyrics:

Kiss, me goodbye and write me while I'm gone

Good bye, my sweetheart, Hello Viet, nam.

America has heard the bugle, call

And you know it involves us, one an all

I don't suppose that war will ever end

There's fighting that will break us up a gain.

Good bye, my darling, Hello Viet nam

A hill to take, a battle to be won

Kiss me goodbye and write me while I'm gone

Good bye, my sweetheart, Hello Viet nam.

A ship is waiting for us at the dock

America has trouble to be stopped

We must stop Communism in that land

Or freedom will start slipping through our hands.

I hope and pray someday the world will learn

That fires we don't put out, will bigger burn

We must save freedom now, at any cost

Or someday, our own freedom will be lost.

Kiss me goodbye and write me while I'm gone

Good bye, my sweetheart, Hello Viet, nam.

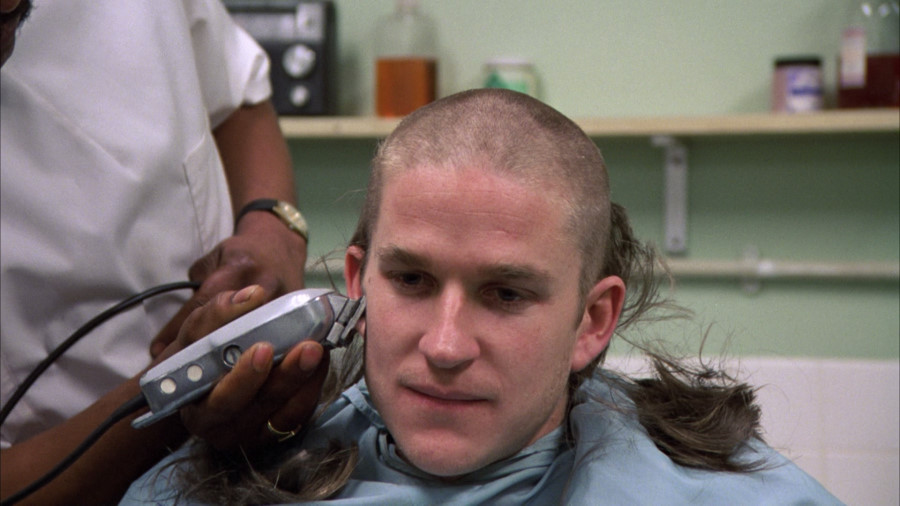

This is a very pro-war song. It implies that sacrifice is necessary, that the freedom of the masses holds weight over the plight of the individual. It does, however, have an underlying sense of paranoia, that 'we must stop Communism in that land or freedom will start slipping through our hands'. As a concept, it's hard to say whether this fear or paranoia is healthy, productive, beneficial or not. But, what is clear here is that a collectively unconscious idea of freedom is essential. In the film, it's implied that this idea is about to consume the soldiers. This is simply done through simple juxtaposition...

Cutting the hair off of the soldiers is a fundamental way of taking away personality. It does this by making everyone look the same and taking away personal choice. So, with the intro to the film, we're told that maybe Joker had a girlfriend, a life beyond the army, but that he is willingly stripping that away from himself. We then move to one of my favourite scenes of all time.

I don't want to delve too deep into this scene as I'm saving that for a later post. But, there are a few key ideas that we need to take forward from this segment. The first is that the soldiers are going to be systematised, stripped apart, and built back up again - they know this. They are later told they're not going to be made into robots, but killers, killing machines. It's this scene that makes you beg the difference between a robot and a machine, furthermore, a soldier and a communist. Semantically, the two are different, but essentially they are the same thing - depersonalised shells that feed a common cause. So, the core idea of this film, and of basic training as a whole, is that there's an indefinable contradiction hidden somewhere within. The next main take away from the opening scene is that Joker joined the marine corp to kill. It's this statement that confirms what the opening implies. Joker has been consumed by a concept, he's committed to a collectively unconscious idea of protecting the masses' freedom. It's exactly this that already has you questioning the film, that has you questioning whether it's right to be pro or anti-war, and to what degree. We all know that violence is bad, but sometimes necessary. This means we need soldiers and military. But, on top of this, very few of us would volunteer to become a soldier and fight. So, what makes the question of pro and anti-war so hard is that most of are made to feel pretty shitty by it. The average civilian wants to be protected, but isn't willing to do it themselves, and so is appreciative of soldiers despite not really understanding them and what it takes to be them. This is at large the collective unconscious surrounding war, violence and the military. We need it, but don't make me join. This idea is at the core of Joker's character and is encapsulated by the theme of fear. However, this doesn't come into play in the first half of the film. We have to wait for that.

So, staying with basic training, I think it's important to notice just how immersive this segment is. It does this by polarising itself against what comes before and after it. It doesn't give characters back stories which seals you into the moment of the film and it is stylistically and tonally a million miles away from the jump into Vietnam. The best way I can explain this is by appealing to all of those who have watched this film through to the end and tried to think about the beginning again. It's practically a completely different film. Hartman and Pyle are distant ideas, as is this image:

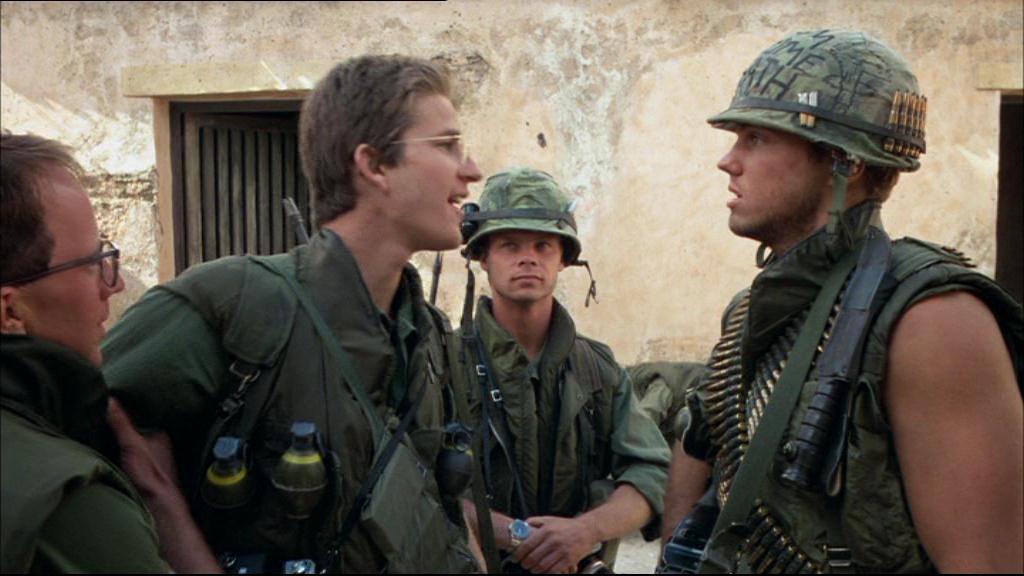

Thinking of the soldiers as bald, stripped and weak is near impossibly after almost an hour of this:

Kubrick ensures this with framing and colour composition. The pallet throughout the first half of this film is grey, white, beige - always bland. The framing is also always regimented, Kubrick always shooting from a distance, ensuring the voidal emptiness of each setting is captured perfectly. On the other hand, out in the open during the second half the frame is almost always crowded. Kubrick only allows space to seep into the top of his frame which only acts as a means of forcing the eye down toward characters. The pallet is also bland here, but with earthy hues, greens, browns, muted blacks. This all gives the impression that we are in a completely different world and atmosphere. It's hostile, tense and you don't want to be lost in it, whereas back on base it's hostile tense, and despite the space, you're trapped under someone else's control.

This control is implemented by Hartman onto the soldiers through psychological contortion. It's by creating a new collective unconscious that Hartman converts his soft boys into men and then into killing machines. This is best understood with two recurrent ideas. The first is the gun, it's the Rifleman's Creed. This is the Rifleman's Creed:

This is my rifle. There are many like it, but this one is mine.

My rifle is my best friend. It is my life.

I must master it as I must master my life.

Without me, my rifle is useless. Without my rifle, I am useless.

I must fire my rifle true. I must shoot straighter than my enemy who is trying to kill me. I must shoot him before he shoots me.

I will...

Before God, I swear this creed. My rifle and myself are the defenders of my country.

We are the masters of our enemy.

We are the saviors of my life.

So be it, until there is no enemy, but peace. Amen.

This is an abridged version of current creed, but captures the fundamental concept. The one thing that is important that is cut out of this version is:

My rifle is human, even as I, because it is my life.

This is the core idea and guiding force of basic training. It teaches the men that they represent a cause and that that cause is war or the sake of peace. This cause is murder and they are to become it, they are to become their gun. There is a key distinction between the gun becoming them and them becoming the gun. The creed states that the gun is supposed to become human. But, what the film shows is that they are to become the gun, they are to become the killing machine. This is the essential element of depersonalisation throughout basic training, and is also the contradiction inherent to the experience that is the ultimate undoing of certain character (but we'll come to that later). This is all reinforced by Hartman's second means of psychological contortion. Hartman is obsessed with...

... dick and balls. The pun in this scene is connected to the Rifleman's Creed:

This is my rifle, this is my gun.

This is for fighting, this is for fun.

It implies that the men have two destructive tools. Their rifle and their dick, aptly named, their gun. Now, if we flash forward to the end, we see the insinuation of this pun.

When his rifle fails on him, Joker reaches for his gun, but fails to use it. Mix this with the constant reference to sex, Alabama black snakes, fucking sisters and having balls you have the phenomena of shit talking down to a T. It's fun, but ineffectual. To pretend it is, is a lie and very dangerous. This is why Hartman beats it into their heads that they are gay, that they like to suck dick, fuck men in the ass - and all without the common decency to give them a reach around. His intention here is to beat the men into the ground, taking away an aspect of their nature, telling them that their personally unconscious impulses are bullshit. This means of humbling his men fails in a certain respect (in respect to the end and Joker) just like it does with Pyle. Hartman wants to break him down to build him again. Before getting to that though, it's best to recognise the moment Joker is broken into.

It's this scene. Having denied belief in the Virgin Mary, Joker is beaten, but sticks to what he believes. He does not let Hartman control his personal unconscious - his belief system. Now, this may seem like Joker, not Hartman, is the victor of the situation. But, what Hartman picks up on guts. Guts is enough. It's the fact that Joker's starting to grow beyond the control of him. This is purpose of the training. It's not to change a soldier's personally unconscious way of thinking completely, but their collective way of thinking and interpreting the world. As mentioned before, a generally collective means of thinking around war would be that it's wrong to kill and that battle is terrifying. That's why we're not all soldiers. Thus, all Hartman has to do is convince his men to commit to the philosophy that was is intrinsically imperative to freedom is violence - action. Again, their rifles must become themselves, they must become their rifles.

Having recognised Joker's new found guts, Hartman assigns Pyle under his command. This is the beginning of Pyle's end, and it's because Hartman is not attacking his collective unconscious any more. He can't get through to him the importance of the corp, the idea of brotherhood the same way he would other men. So, instead he allows the corp to 'persuade' of what is right and what is wrong. That's why this...

... is what breaks Pyle. Kubrick tell us this. This moment only happens because Pyle leaves his footlocker unlocked. The footlocker is metaphorically Pyle. It being unlocked is not a good sign - it's weakness. Inside Hartman finds the symbolic weakness of Pyle's character. It's good food. Pyle most probably so fat because he enjoys eating - it's where he find happiness. The same goes for the rest of the men but with sex. This is why Hartman attacks them on this basis, the men bounce back though, still obsessed with dick and pussy until the very end. Pyle doesn't have the capacity for this. He's broken into and stripped of all personal character. Further this with the corp raining down on him a shit storm of soap blocks and you can see how both his personal and collective unconscious is being conditioned against himself. He's being taught that he should hate himself and that he's simply not good enough. This would be ok, if he had conditions by which he could otherwise be accepted (like the other men with their bravado). They have their guns and they have brotherhood. Pyle has his gun, but no brotherhood. He's an unprogrammed killing machine. This fault brought about by a misguided method of conditioning has him destroy his creator...

... and then hit self-destruct...

It's in this that we can understand the term Full Metal Jacket. It's in reference to the loaded clip in a gun, but remembering that the rifle is metaphorically the soldier we can see Pyle as his gun - which explains why he says the Rifleman's Creed before blowing himself and Hartman away. Pyle almost wears his gun, a Jacket, and for it to be full of metal suggests he is nowhere to be found. That he is empty, a shell, and that that shell nothing more than a symbol of violence.

It's here that we get an abrupt jump to Vietnam, a jump that practically disregards the most powerful scene of the movie. Because this is a story told from the perspective of Joker this is completely understandable. He puts the memory of the training camp and Pyle at such a distance from himself that it might as well not exist (repression). He did the same thing in the beginning of the film with his life as a civilian. What remains though is dick and balls, personal unconsciousness, id immersed impulse - which is exactly why you then immediately get the infamous 'sucky, sucky' and 'me so horny'. The proceeding movement through the remainder of the narrative is a conglomeration of contradictory scenes. This is best seen through the night of the Tet offensive. It proceeds constant and flagrant shit talking by all men about 1000 yard stares, John Wayne and the illusive shit. The only words when the bombs start falling and the gooks start raining down on them though are I'm not ready for this, and Amen. This happens time and time again in escalating circumstances that eventually take us to the very end. But, before jumping to that, we have to make clear the driving theme of the second half of the film. Fear. Fear is not a bad thing. Fear is tantamount to intelligence in many circumstances, it's simply knowing when not to put yourself in danger. The only reason why fear isn't law though is because sometimes you have to fight. But, looking at the context of Joker's war and the serious doubt of the general public regarding it, it'd be hard to not hold onto fear as law when fighting the Viet Cong soldiers. This is why Joker doesn't join general infantry, but is assigned to journalism and war correspondence. This job keeps him out of the shit, and introduces us to a very important figure:

Lockhart knows the shit and he didn't like it, 'too dangerous'. It's then fair to infer that this character is simply a more experienced version of Joker. With the end of the film, Joker having killed the young girl, it's easy to see him crawling back to the office and keeping his head down and dick between his legs until the war is over. That's if he makes it through the remaining battle around the Perfume River.

The reason why fear is so important to the latter half of the film is because life, living and surviving basically comes down to stupidity and brains replacing just guts. Most importantly the psychological battle is now completely dependant on unconsciousness. Fear is intrinsic to human nature, and so is a very important tool. In circumstances such as battle, fear is an important factor. Pure fearlessness probably isn't a good sign. It can make you feel invincible, but will block rational thought. And stress is probably one of the best drugs for speeding up, streamlining the brain, forcing you to rely on your unconscious reflexes whilst making higher and pragmatic decisions. Stress otherwise known as fear. This is not to say that fear can't kill you. Fear can lead to hesitance, can lead to frivolity, which'll kill you quick. There must be a balance is the point. And it's with the ending that Joker considers himself fearless, which for him means stupid. For the likes of an Animal Mother on the other hand, well, it's in the shit and under fire that he supposedly becomes one of the finest human beings. The lasting take away is then that Joker has devolved as a character - or at least tells us he has. He, in short, looses the strength of he had in this moment:

The final thing to look at before the ending will be the general collective unconsciousness of a soldier in face of his personal unconsciousness. We see general unconsciousness in battle with the need to survive and kill, but near the end with the interviews a small piece of the soldier's personal opinion is presented. What's interesting about this is that the political facts of the Vietnam war are never said explicitly, neither is the true emotional experience of soldiers shown. We see aftermaths and snippets of bravado - all acts. Truth is much better presented by Apocalypse Now and Platoon, What the interviews demonstrate though is that, to this film, the personal and varied opinions of people have more weight than the facts. Through this we begin to see a kind of zeitgeist, a specific and nuanced set of collectively unconscious ideals. With the soldiers we are then seeing a phenomena of behaviour that is not really a generally collective unconsciousness. This is because it's not exactly normal for the average person to want to kill people - even for the sake of freedom and the possible risk of losing it all. Taking this into the final battle where Joker loses the last of his friends and ends up killing a young girl, he's soon forced to recognise that his personal unconsciousness has slowly been taken over. He has become a Metal Jacket. He has no true personality, maybe all that remains of it is a distant echo of childhood - which is why he and the men sing the Mickey Mouse Clubhouse theme. This is the final sombre realisation of character in this film. Everyone devolves or dies. Everyone who tries to do the right thing, remain positive or tries to be intelligent, dies. Anyone who shows compassion is shot down or attacked - and all so everyone embodies a contorted collective unconsciousness. The duality of man is broken down by the end of this film. War has a monopoly over these boys.

The message of Full Metal Jacket then becomes obvious. It's about consciousness, not unconsciousness and it comes back to Jung, Freud and psychology. The first step of solving a problem is always recognising that you have one. Why is this? It's all to do with consciousness. You need to have a conscious grip on what could be a unconscious driving force - the problem. When you're admitted to therapy, it could be CBT, free association or even dream analysis, you're taught how to monitor what you feel and how to deal with it, how to break it down and know what is effecting your unconscious state and how that is effecting your behaviour. What then seems to be most important is simple self-awareness. This is the key to a myriad, maybe even a lot, of psychological issues. It's knowing how to deal with yourself (yes, sometimes with the aid of drugs). But, to then deal with yourself you have to have some kind of idea of who you are and how you got there. You mustn't be the product of someone else - something alien you don't understand - like a marine corp, or worse, war.

The final thing to pull apart is then the difference between killers and robots. Robots don't know they're conscious. A killer does. This is why collectivism, being a soldier or joining the army is not a bad thing. You can be apart of the system without becoming it. The system often wants to consume you. What Full Metal Jacket argues is that you simply can't let it do that, and that your strongest defense is psychology, it's ultimately knowing who you are and what that Jungian thing is.

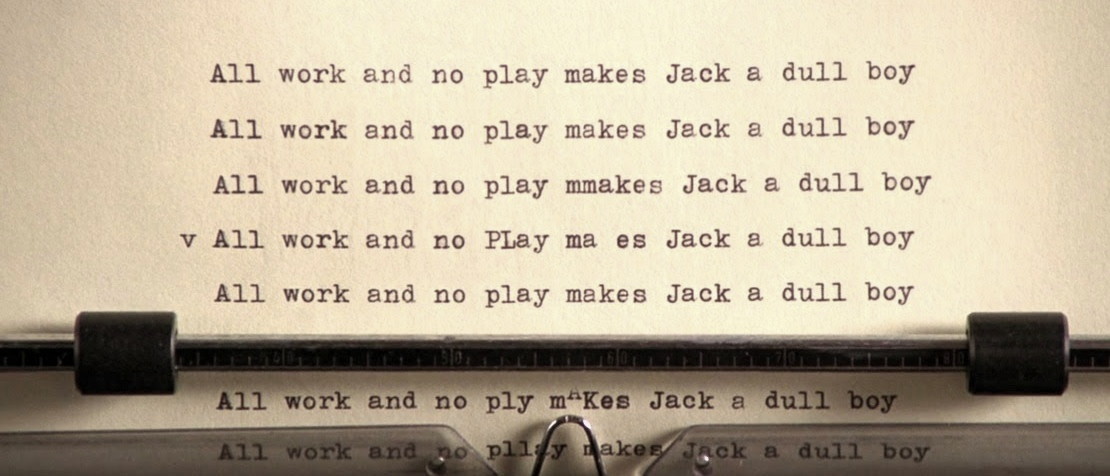

Psycho - Marriage And How Not To Do It: Him And Her In Two Parts

After stealing $40,000 Marion Crane runs out of town where rain drives her into the Bates Motel.

.jpg)

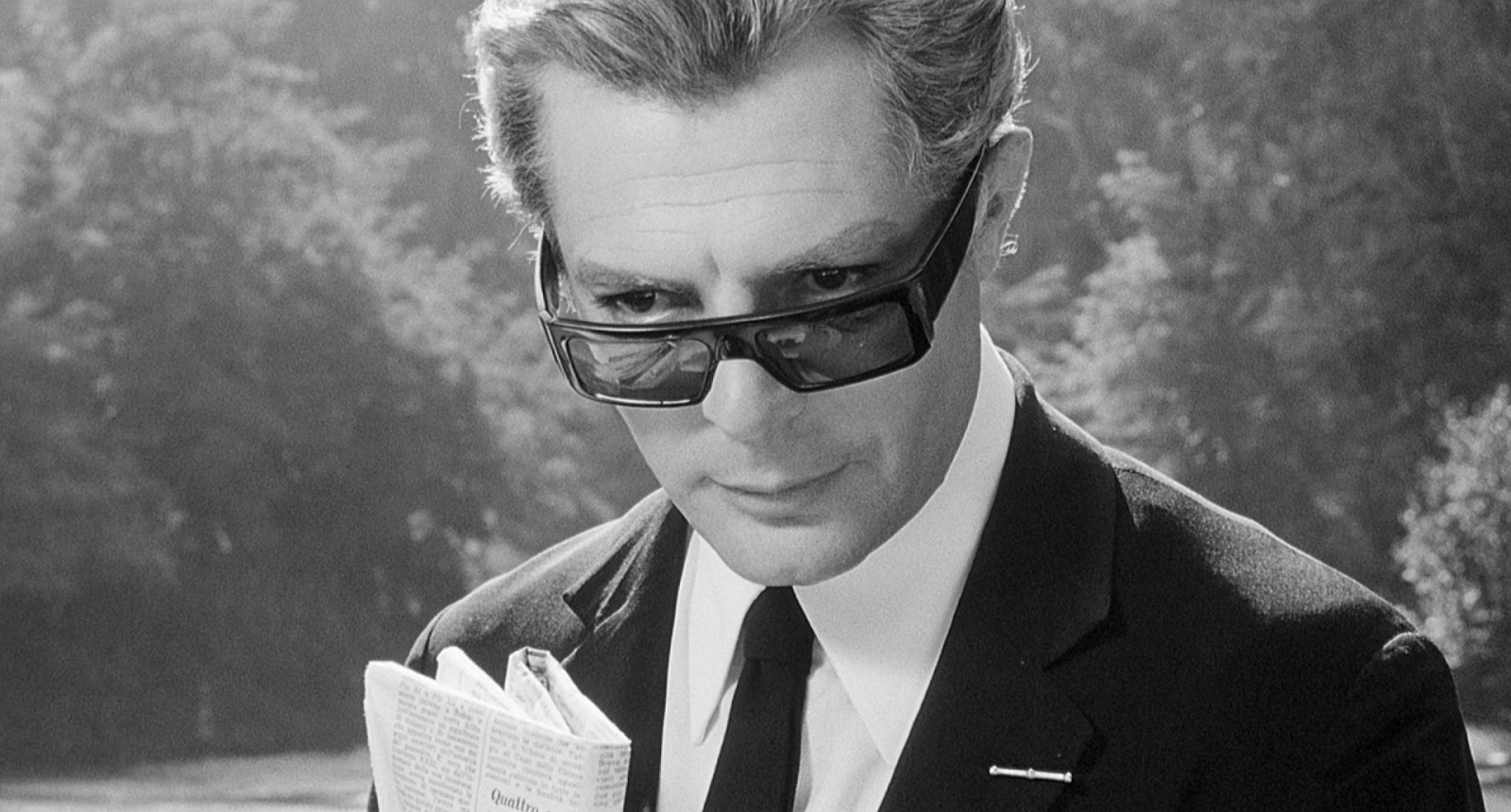

There's many ways to watch Psycho. Firstly, you can try the perspective of an audience member looking for 1 hour and 45 mins of entertainment - of suspense, horror and mystery. Secondly, you can look at this film from a technical perspective, analysing Hitchcock's developed style and philosophy of cinema in action. Thirdly, you can again look at the technicalities of this film, but from the writer's perspective. This is my favourite way to look at a film as, for me, it's the most rewarding perspective to take. You get the experience of entertainment, a hidden kind, as well as a lesson or interesting debate simply by choosing to see implied greater depth. This is what I want to do with Psycho today - to look at this great lesson in direction, this intriguing thrill ride and pick apart the allegory. Now, the underlying story of Psycho is of marriage - a pretty bad one. This is a film about two dysfunctional interpretations of a to-be married life. In short, Marion looks for security in all the wrong places and Norman... well, he can't find a woman better than his mother. The climax of these two conflicting ideas is rather sudden...

... which leaves us with a film of two parts. The first section that sticks to Marion's perspective is all about putting yourself in danger, leaving the latter half with Norman to be about a contorted view of women and social exchange.

The opening with Sam and Marion in the motel room is what plants the seed for everything to come. After having 'spent lunch together' the two dance around an idea of commitment. This all comes about through the buzz word respectability. Marion, in short, wants a normal relationship, an engagement and then marriage with Sam. He is, however, reluctant because, firstly, he's been married before and secondly, has very little money. This establishes two important facts. The first is that Sam is still paying his father's debt. For anyone who's seen the film recently or knows it very well, you'd be able to make the first link to Norman here. Norman's father died when he was 5 leaving him and his mother alone. The metaphorical debt Norman was laboured with was of affection, the fact that a son is no substitute for a lover. This is what caused Norman to snap and is used to imply that the two (Sam and Norman) share common traits. These traits are to do with the perception of affection and commitment. To go a step further on these themes we simply have to look at the fact that Sam still pays alimony for a wife he clearly doesn't like. His fear of commitment may be grounded in his childhood (like Norman) but accentuated by this recent past. This leaves Marion making the compromise that 'she'll lick the stamps'. She chooses to take on Sam's personal luggage. This luggage is primarily monetary. Sam doesn't have the money to marry, get a better home for themselves and so on. Marion takes that onto her shoulders - something that'll carry through to a fast approaching moment. The lead up to Marion stealing the $40,000 is plagued with talk of being married and getting married, both by her co-worker and the rich customer, Tom Cassidy. The importance of Tom is found in the idea that you can buy unhappiness off. He suggests to her that with money, life is easier. We've touched on this subject before with The Matrix, but what this concept boils down to is context of self and situation. Can we make the things around us better? But, more importantly, the way we interpret them more productively? Apply this question to Marion and we see that the way she wants to buy off unhappiness is to secure a home for herself and Sam so he'll hopefully commit to her. But, it's when she starts to question what exactly she's doing that things start to go awry.

The way in which Marion's anxiety and situation is best revealed and then poked at is with the scene where she exchanges her car. Her own car and the one she trades it in for are both displaced euphemisms. They represent Sam and his choice of women (as well as a more general idea of choice). Sam seems to have jumped from a wife to a girlfriend without recovering, without being able to commit to someone again. This is evident in the way he only wants to be around her for a certain ease of access. The response to Marion's high pressuring, both in the car lot and with Sam, is crucial to her growing anxiety. This is because rash choices are always indicative of a mistake to be made. Just like Marion renting a new car is something you might want to slow down a little for, maybe take a test ride, so should be Sam moving into a relationship with Marion and Marion with him (no intended euphemism, well, maybe - but, the test should also be of each other characters). The overall purpose of this scene is to build suspense, to have Marion question herself and the way in which she makes choices in life.

So, as a result, with Marion back on the road her anxious thoughts concerning being caught with the money swell. But, because the money and subsequent anxieties are all connected to Sam and her future with him, it's fair to infer that she's having doubts concerning their relationship also. These doubts are made clear with the pathetic fallacy - the rain. Marion's view of her future, of the road ahead of her, is obscured. The only light ahead of her now reads: Bates Motel. Vacancy. The neon sign is, for Marion, enlightenment. Whether it's of paranoia, or sudden realisation, the Bates Motel makes clear to her the dangers of the road she wants to travel down.

It's at this point where we see the exchanging of the baton from Marion's perspective to Norman's. This exchange though is very ambiguous and has had me stumped for quite a while. As has been implied already Norman's situation and perspective are similar to Sam's. Both seem to have problems with women, but Sam's is in no way as serious as Norman's. I have tried to find more strong links between their characters to maybe suggest that they are the same person, but can't agree to this with any confidence. What I think may be possible though is that this narrative might just be under the complete control of Marion. By this I mean that we see everything from her perspective. So, whilst Norman and Sam aren't the same person, Marion may be hyperbolising his character to express her anxiety captured in this part of the film. In other words, to her, Norman represents Sam. This all suggests that Marion doesn't die, and her body isn't discovered in the end of the film, but that she decided the relationship between herself and Sam is going anywhere and that it dead in the water - or would it be swamp? Either way, this would transform the whole narrative of Psycho into a pure extended metaphor. But, the fault with seeing the film in this way is the task of having to assign so much meaning to so many extraneous characters. I've tried watching the film a few times over with this in mind, but haven't yet got a clear image of what everyone could be representing, which leaves me questioning the validity of the idea. However, what I think is valid and self-evident is the theme of marriage throughout this film. When you apply this to the two main characters you get our narrative of how not to approach marriage in two parts. And what this is all centred on is an idea of freedom. This is symbolised with Marion's last name, Crane, and Norman's stuffed birds - all symbols of freedom.

This all turns the most poignant and immersive scene in the film, that is simply Norman and Marion talking, into the all important no man's land. This is a no man's land of conflicting metaphors. For Marion the birds and the freedom they represent are a positive idea - it's what ultimately has her decide to return the money. For Norman, freedom is an unattainable goal, moreover, in other people this scares him. We'll start with Marion. It's sitting with Norman, a clear mummy's boy, that she realises that for her to be with Sam will simply mean she becomes his mother figure. She'll pay his alimony, work the harder job, and probably still have to be the classical 50s housewife at the same time. And, whilst that sounds like a pretty shitty deal, there's a small detail she's skipped over. The money she wants to use to give herself and her possibly non-committal boyfriend is stolen. The freedom the money gives her is actually her own personal trap. And that's why she leaves early in the morning - to get out of a personal trap back home. However, before she gets the chance to leave, she is of course murdered.

The irony and implication of this shot is that Marion's means of freedom (the money) remains. It's her initial trap, her relationship with Sam, that metaphorically...

,,, destroys her. It's that which she thought she wanted and could handle that was the true conflict all along. This is why this image:

The zoom out from the eye is incredibly important. It implies that she maybe saw this coming, or that it was the last thing that she'd expect - Norman, a hyperbolised representation of Sam, killing her. To side with the former, that the image of her eye implies she saw this coming, is to suggest that Norman is a strict and purposeful representation of Sam and that we see the rest of the film from a dead woman's perspective. To side with the latter, that Norman killing her was the last thing she'd expect, it's implied that the trap she got herself into with Sam/Norman was too strong. This marks a futile maybe even pessimistic perspective of marriage or future relationships in Marion. Through allegory it's suggested that Marion's anxiety or her own personal flaws (choice in boyfriends) is what consumes her. She destroys herself in a certain sense.

Now, jumping back to conversational scene we can shift into the second part of the film as seen through Norman's eyes. It's Norman's perspective of birds and freedom that set up the negative male perspective of marriage in this film. And it's from this point that it's probably best to see the first section of this film as a negative female perspective - the second, male. This will simply help to widen the allegory and clarify the narrative message. So, if birds are a symbol of freedom, for Norman to stuff them implies he wants to control and ground others. We're not talking exclusively about others here, but Norman himself. Like Marion, he has his own personal traps. And it's the reduction of marriage to a trap that is the main fault of both ends here. Marion can't be tied down to the wrong person, and Norman (like Sam) can't find the right person to be trapped with. For Norman, his mother is the only female he can bind himself to. And it's in the end of the film that we figure out that he does this out of guilt. His mother only comes through his personality as a repression of the memory of him killing her and her lover. Love to Norman is then nothing more than a plug over a deep hole in his persona. It's implied that he, the mother side of him, kills women because of this. He destroys what he can't control in other words - this is why he doesn't like women and strays from relationships. Norman can't replace the hole in his persona taken up by his mother without exposing himself as a monster. It's here that you can see the fundamentals of a recurrent character in modern cinema:

Both Scorsese and Nolan have taken Hitchcock's theme of marriage in hand with the psychological crime thriller and used it to explore this idea of traps, of refusing to see yourself as a monster. In fact, there's a plethora of male characters that the Bates archetype has been built from and revised by:

I could give a million more examples, but all of these characters, like Norman, are driven by a conflicted idea of love (or lack thereof) that they allow to consume themselves. This is an interesting idea to me as the reverse to this kind of characters is:

It's these men that fight, that risk everything they have, for the memory of a loved one, for the safety of someone they hold dear, or to simply stand triumphant and shout: 'Adrian, I did it'. What this all says is that under the theme of marriage there's two key male archetypes. There's the Bates archetype and the Rocky archetype. When you juxtapose these two types of character you can recognise a huge swath of films as romances. When you usually think of romance, you think of Pretty Woman, The Before Trilogy, Titanic, Breakfast At Tiffany's, Casablanca. The likes of Man On Fire, Rocky, Die Hard, Taxi Driver or even Psycho don't come into this picture. Granted, some of these films are tragic, but, what's the most famous romance of all time? Romeo And Juliet anyone? The point I'm trying to make here is that there's two reactions to the idea of romance. There's the male-centred idea of tangible romance, of actions and reactions. On the other hand there's an intangible idea of female-centred romance based on non-verbal cues and emotions. The best way to clearly convey this idea is to look at where the final or solidified 'I love you' comes in the film. With tangible, action/reaction romances the 'I love you' comes early on. These are, almost paradoxically, manly romances. Look at the examples given. It's romance that comes before the fight in Unforgiven and Rocky. With Man Of Fire, the relationship between Creasy and Pita has to be developed before the action can take place. Even in Die Hard John is going to New York to visit an ex-wife and family. The relationship is present beforehand. The stereotypical romances, however, end on the solidified 'I love you'. Just look at examples given: Pretty Woman, Breakfast At Tiffany's, Titanic, Casablanca. The first two end with a kiss. The second two don't end too well for the main male protagonist, but the female lead learns her lesson in romance with the final act. Now, bring into the equation the Bates archetype and we can see them as characters unwillingly forced into the latter stereotypical romances much like Pretty Woman, Breakfast At Tiffany's, Titanic and Casablanca. Bruce Wayne, Travis Bickle, Norman Bates, Guido Anselmi and so on are tasked with finding romance in their narratives. This is only ever used to reveal incapacity though. It's used to reveal a monster within them.

What this all suggests is that in popular cinema the man in the woman's position of a romance turns the film into a horror or a take on a psychological crime or mystery. Added to this, the woman put in the position of a male romance (Die Hard, Rocky, Man On Fire) also turns the film into a horror or a take on a psychological crime or mystery. Norman is tasked with getting along with a woman, and as representative of Sam, he's tasked with living under her wing almost. Rose in Titanic could handle this, so could Vivian in Pretty Woman. Not Norman though. Moreover, Marion steals money and keeps from danger to ensure a chance of romance. Rocky could do this, so could John McClane. What's going on here? Well, the wider answer could be that role reversals aren't that acceptable by the standards of society. This is probably true to a certain extent. Is that good or bad? A talk for another time. In terms of cinematics, however, what this seems to be about is fear and traps - that which Psycho is inherently about. Personal traps are the product of fear that is allowed to consume. For Norman it's fear of memory, Marion, fear of being wrong, Travis Bickle, fear that the world will never be a better place, Bruce Wayne, fear that evil will consume all, Henry Spencer, fear of fatherhood, Patrick Bateman, fear of being ignored. And it's this element of fear that these characters are either subjected to or try to fight against. It's for those reasons that their films are often crimes, horrors of have elements of action. When we come back to the key archetype of this class of film, Norman, we can understand the overarching philosophy of these broken romances - and it's all connected to Hitchcock's idea of marriage. Marriage seems to be about knowing yourself well enough so you don't screw up someone else's life. It's not letting bias and memory dictate how your present perception functions. Unfortunately, with films like Shutter Island, Memento and Psycho where the Bates archetype is strongest, the best characters can manage is to convince themselves that they are not the monster...

And it's in this that an anti-romance almost becomes a romance. In the end, Psycho, like many other films is simply about self-awareness for the purpose of social-awareness - those around you. For both Marion and Norman it'd be knowing the traps they put themselves in and have to get out of that'd allow them to better cope in life and with relationships.

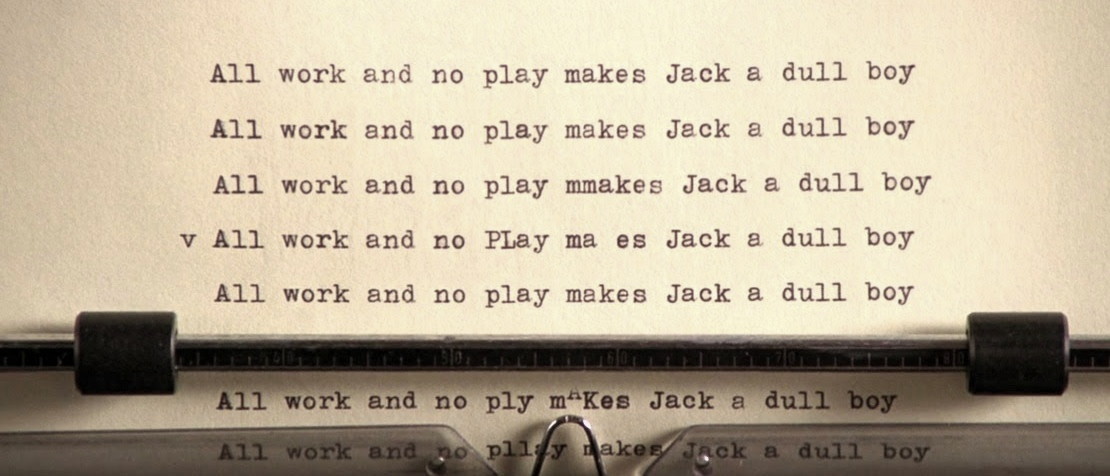

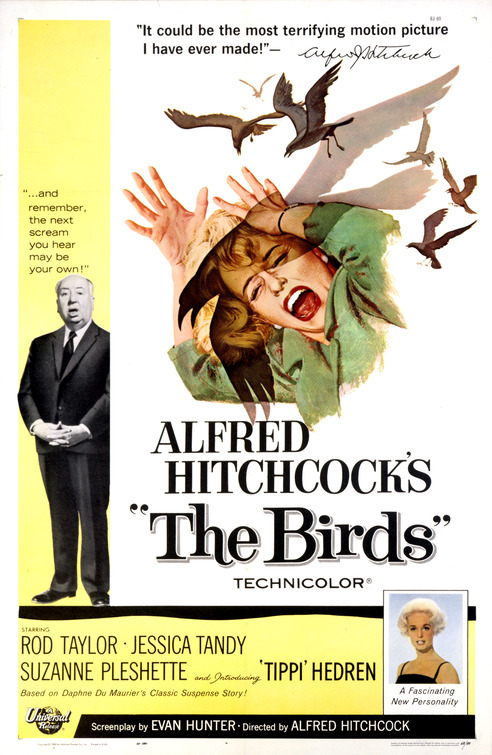

Melanie Daniels follows romance to a small beach town about to be attacked by huge flocks of birds.

This is not a good film. It most definitely hasn't aged that well, but, that doesn't really matter. It was crap to begin with. My primary argument on this is that it's utter nonsense, moreover, the acting is mediocre, characterisation flat, plot more than disinteresting and the logic... wow... the logic. But, most of all, this film is in no way horrifying - not to me. I don't want to rip into this film though for it does have some redeeming qualities. Its bat-shit-crazy narrative and insane character motivations (to run into flocks of somehow killer birds) is driven by a singular metaphor. The birds are in fact Hitchcock's way of presenting the social atmosphere of the town and relationships between characters. The birds of course start as a humorous euphemism with the love birds, but become violent when the plot moves into Bodega Bay. It's here where sea gulls, crows and sparrows attack - even the chickens are a bit off. This all comes down to the relationship between Melanie and Mitch. Mitch seems to be some kind of player who has mummy and daddy issues. This should be ringing many alarm bells - especially if you've read my post on Psycho. (Links in the end). Hitchcock uses birds in the same way he does with Norman and Marion in that they represent a possible relationship. In Psycho the relationships in question are between Norman and women as well as Marion and Sam. With The Birds it's between Mitch, his family and Melanie. In short, Mitch's family are in a slight upheaval with his father having died, leaving his mother needing a trustworthy son and his sister a role model. The women he then chooses to bring around have a huge effect on his family's dynamic. Moreover, the conflict between Melanie and Mitch's family permeates throughout the whole town - it being small and gossip being capable of devastating the family. This results in the birds attacking - an expression of said hostility. You see this clearly with every scene revealing character, such as Mitch's and Melanie's back stories, proceeding an attack. Moreover, every time their relationship progresses, the birds grow violent. This ultimately plunges the town into chaos and puts many in danger. This somewhat abbreviated explanation of what the birds are then allows you to recognise the question posed to both Mitch and Melanie who are at fault (metaphorically) for the bird attacks. The question posed to them is whether they want to stick around town and make this film a horror/tragedy much like Romeo And Juliet meets Psycho (but with birds replacing knives) or leave for the sake of preserving a healthy family circle. And it's with the end of the film that all the characters learn to trust and respect one another, so they can leave the town with the ex-girlfriends and painful history to start again.

It's by comparing Psycho to The Birds that you get a nice juxtaposition of how to overcome memory and convoluted social ties to move forward in life - not get stuck.

The infamous surrealist short from Dalí and Buñuel.

Unbeknownst to any of my viewers, I've wanted to talk about this film for a long time, and have even tried once or twice. I've wanted to write about An Andalusian Dog because seeing it for the first time was a formative cinematic experience for me as a writer. But, when I've tried to talk about the film on the blog before, I wanted to discuss all of its minute details, explaining what each moment could mean, or what they mean to me. This, however, never panned out because this is a filmic experience, and in itself, a film, that is almost opposed to that philosophy. It's in my writings that Un Chien Andalou has inspired ambiguity, inspired imagery that may be imbued with implimence, but not concrete, equative meaning. And it's surrealism, that which Buñuel and Dalí portray, that attempts to reveal the Freudian subconscious through sensory and emotive cinema. The according philosophy of surrealist film is then of irrationality, is of a nature you cannot nomothetically pull apart and explain. It's then this philosophy that is opposed to what I've wanted to, and in large part do, on this blog - explain movies. What Un Chien Andalou instead represents and teaches anyone interested in cinema is the fundamental idea of fantasy and imagination inherent to the art form. I've talked about this subject of fantasy before with posts like those on The Matrix, but fantasy is an extension of the human imagination that isn't satisfied. Tarkovsky says is best with:

His point here is not really that the world is imperfect and that it should be better. His point encompasses the artist in respect to perspective. We create art because we see the world as imperfect, we look around at cities, at oceans, the sky, space beyond, technology before our faces, under our fingers and we look through organic devices attached to incomprehensibly complex structurings, chemicals, pathways and interactions yet we still want more, we think this is not good enough, or, at the least could be better. I daren't critique this kind of thinking because it is inherently human and to deny drive, to deny need and want, to deny curiosity, would be to lie. Instead, what I'm trying to demonstrate, as I think Tarkovsky may be, is that we project the ill-design in us onto the world. It's drive, need, want, curiosity that both gave us electricity and medicine, but also war, greed, suffering in ourselves and put upon others. If we didn't have the human ingenuity and agitation, we would be a bunch of mindless hippies in love with the universe at best, but a horde of animals, in tune with nature, but completely unaware of our existence in all probability. The world, to the hippie and horde, would be perfect - and only because their internal schematics saw it as such. So, Tarkovsky's point and mine is that art comes from imperfection. Take that a step further as we just have and we can recognise art as coming from need, drive, want, curiosity; from an irrational human essence, something broken within us. How this irrationality has been most accessibly explained is with Freud and his theory of the unconscious mind. Whether its with complexes that have us want to sleep with our mother, or play with our faeces, Freud sees breaks in the wirings of the human mind that express themselves without our say-so, or know-so. This expression is fantasy, dreams and buried associations of memory and emotion. When you look at the world, especially of art, through the Freudian looking-glass you fall down a postmodern rabbit hole where meaning is so fruitful it's almost negligible, no one idea much more helpful, nor valid, than another. To clarify, it's best we turn to our film at hand, An Andalusian Dog.