Inaffection Series

To preface this, I must bring to light the strange 'schedule' of this series. The first post was written in June of 2016, the second August of 2016 - and the rest fall between the end of July and the middle of August, 2017. Without wanting to make any excuses, all I'll then say is that this is just as much a window into how this blog has changed over a year as it is an opportunity for greater insight into the screenplay. I hope you enjoy...

A wicked stepmother enslaves her innocent stepdaughter, but when a chance to go a royal ball arises, so does a chance of freedom.

The majority of this is nonsense, just as a kid's chant or song of this nature would be. Take away sense and reasoning and just believe, then life becomes easier. That means that the metaphor of this scene is that Cinderella fixed some kind of dress for herself and went to the ball - she persevered. What you then have to infer is that the dress is also a metaphor. This is all a given if you can accept that the animals are mere projections. The mice, Bruno and Major all transform, indicating a boost in Cinderella's confidence. In short, she's using the idea of her father as guidance - he acts as a chaperone. But, staying with the dress, what we are seeing is hope toward social transcendence. This is also why the glass slipper is the most important symbol in the film. The dress and slippers are a facade that gives Cinderella confidence, but they are also the true manifestation of her hope. The shoes are glass, however, because the hope, the dream of Cinderella overcoming everything is fragile. Nonetheless, she meets the prince, she does dance, and most importantly, she keeps the slippers. This implies that what remains after the night is Cinderella's confidence. She manages to keep her dream alive, she is able to hold onto an idea of love.

It's now that we can jump to the end of the film. Here the figurative entrapment of Cinderella becomes literal. To fight this she needs a bit of help from her projections. It's Gus and Jaq, the two conflicting ideas of her self (the good and bad, or the better and worse) that have to work together to get the key. Opening the door isn't that easy though as the domineering idea of the stepmother steps in. However, lessons, or ideas of Cinderella's parents finally come into effect. First it's her mother, then it's her father, who gets to exact his revenge on the woman that betrayed them. This kind of means that Lucifer dies and Bruno (the father) killed him. I mean...

... but, don't worry. This isn't literal. Cinderella merely relinquishes the idea of her stepmother from her mind. Even if the cat dies, so what? He was an ass. I don't like cats, what can I say? Anyways, meanwhile, downstairs the glass slipper is being tried on by Anastasia and Dizella. The key plot hole here is that the slipper should be able to fit an awful lot of girls in the kingdom. This is why recognising it as a metaphor is so important. It's a metaphor for Cinderella's virtue, Cinderella's strength, hope and resilience. This is what is unique to her. This is what no other woman in the kingdom has. This is what the prince is really looking for. So, in the end, the one slipper can break, all of Cinderella's faith and hope crushed by the stepmother's jealousy yet again, but, it's just not enough.

She has the other shoe. It's then because of this that she can live happily ever after. Why? How? Happiness, just like hope has been thoroughly demonstrated as being a mindset that allows you to act. When you've been through what Cinderella has, when you've been through massive psychological duress and pressure, but made it through by the strength of your own will, you've proved your ability to cope. This is the true message encapsulated by the 'happily ever after'. Cinderella has learnt a life changing lesson. Because she is capable, she will ensure she lives that happily ever after.

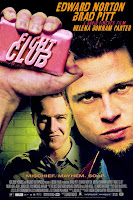

An insomniac runs into a soap salesman.

We've all seen it. And so the warning is pointless, but, SPOILERS. Tyler Durden is a projection of The Narrator's screwed up mind. With that said, this is a movie entirely about self-destruction sourced from a simple lack of identity. Fight Club is a movie much like The End Of The Tour, but more extravagant with an exuberant, boisterous and hyperbolised style, movement and characterisation. This is then a movie that is, at its core, pretty petty. However, the truth of this is presented in a manner you can take seriously, in a manner you don't feel you must mock. So, the core of Fight Club is of a man that is simply not happy. To combat his depression he wallows in it, but when he can no longer feed off his own bullshit, he decides to hit self-destruct. His self-destruction through Tyler is actually tantamount to us not being able to take the plights of this movie (or something like The End Of The Tour) seriously. The narrator knows his problems are pretty pathetic, he knows that going to the dozen support groups he has no place in joining is pitiful, pretty scummy and completely self-absorbed. It's with Marla that this narcissistic essence of his self becomes unbearably upfront. This is what triggers Tyler. Tyler is nothing more than a way for The Narrator to punch himself in the face and stuff Marla without having to recognise the fact that he is both pathetic and could maybe push a way out of his depression. The paradigm of this film is then all about a reflection of self. In the very beginning, The Narrator is forced to look in on himself and see nothing. He stays up night at day, simply wanting reprieve. He hates his job. He hates the system he is apart of. He wants out.

To understand The Narrator's position you simply have to see him in an empty room. There is a door and it's unlocked. The Narrator wants out. What does he do? He walks to the door, pulls it open and leaves, right? Ok, but what if The Narrator can't walk? The door is now shut in spite of him, his efforts, his need to translate thought to physical actions are fruitless. It's now that we see his depression, his insomnia, his debilitating lack of perceived self. He sees himself as empty and so is powerless to leave his unlocked room. What happens if, in exchange of locking the door, we give The Narrator a friend with a bomb? He still wants out, but he's not moving. Why not let the friend destroy the room around him as he stands? This is the entire narrative of Fight Club. The Narrator senses a vacuous hole beyond the shell of his skin, and this makes him feel like absolute shit. To escape this, he projects the shit onto the walls around him. He then decides that if he wipes the walls clean, maybe wipes them away completely, the shit inside him will be gone too. What we see here is a cushion of nihilism being popped by a pin of anarchy. The Narrator doesn't believe in himself and so he doesn't believe in the world. He decides he wants to lose control, he wants to play with his internal self-destruct button, and then he decides the world's self-destruction also needs to be hit. This translates to Tyler's plan to destroy all monetary and capitalists aspects of society instead of The Narrator searching within himself for a new beginning. This trait of The Narrator and Tyler is immersed in a plea to the world to stop letting them (him) destroy themselves (himself). In short, it's working a boring job for money and to simply accumulate things, that are so easy to do, just like watching TV, living a safe, quiet life by everyone else's rules. However, we choose to live the easy life, to indulge in shit that's not good for us. Is it right that the world then be labelled corrupt? Is it right that we then think the system needs to change? Does it make any sense that what we feel in side is irrevocable attributed to the world around us along with blame and consequences to come?

This is a question Fight Club begins to ask. However, this is not the last interrogative given by the final image of the film...

What this image caps off is the end of a cautionary tale. The Narrator and Tyler alike, no matter how enjoyable they are, no matter how convincing their case for anarchy feels, are (somewhat inadvertently) liars. Don't get sucked into what they preach. That is not what the film is about. As said, this is a film about finding yourself. It's subsequent commentary then comes with how people tend to approach this perpetually distancing peak that is ultimately insurmountable - knowing just who you are. Again, this is a film about finding yourself, about finding your own individuality, and it starts with The Narrator breaking away from his shirt, tie and suitcase by beating himself and friends up for a laugh, to actually feel, to experience physical truth. It's the beginning of the second act where the nihilistic and anarchistic elements of this film teach lessons that actually help The Narrator. What The Narrator and Tyler start off doing is simply chipping away at the hatred they have for themselves. They feel weak and pitiful and so they ask themselves just how weak and how pitiful they are. They test and find this out with Fight Club. And it's, as Tyler says, Fight Club that is truth, that isn't bullshit and lies. What's bullshit is The Narrator's boss being a better person or having more power than The Narrator just because of a title. This social hierarchy is what we all experience every day. It's having to be polite, having to be passive aggressive, having to not ask someone who believes they are better than you to actually prove it. It's the monetary and capitalist aspects of society as presented by the the first two acts and all of the workplace scenes that demonstrate how we live in a society where we fight with metaphors, with implimence, with intangibility and hidden agendas. And the rules of this world remained undefined as we simply aren't able to talk about them. And it's that there that should be ringing all the bells. We all know it:

These rules are a massive fuck you to the way we operate in a civilised society where we have to be passive aggressive, we have to be fake and lie - and never talk about that fact. The first two rules are then a dare to actually say who you are, to actually say what you feel you must not, to talk about Fight Club despite authority. This is a paradigm repeated throughout the film. In fact, it's after Tyler and The Narrator have their beers over The Narrator's apartment blowing up that Tyler demands The Narrator actually ask if he can stay at his place. This is the best example of social conduct being thrown out the window in search of honesty. Tyler knew what The Narrator wanted to ask. The Narrator knew that Tyler knew. Still, he keeps his mouth closed as it's the polite thing to not be upfront, as he didn't want to force a yes, or hear a no. These touch and go rules of society keep us from truth, keep us from being honest with one another and ultimately separate us all. I don't believe this a universal truth, and I don't think we should be unconditionally honest. But, more honesty in our world is something that wouldn't go amiss. This is a concept explored by another film...

... so maybe I'll save that talk for another time. Nonetheless, honesty is all Fight Club represents, is all Tyler and The Narrator are in search for in the first half of this movie. The subsequent rules of Fight Club reinforce this:

Think about these rules, not between two people fighting, but talking. If we could be honest enough to say how we truly feel, about our boundaries, about truly pushing to the fringes of what we're capable of, we would be able to see true character in others. We wouldn't be coddled by cushions of social conduct. I remember hearing a Joe Rogan podcast, with Duncan Trussell, that dipped into these ideas with emojis and texting. Trussell spoke about emojis being like hieroglyphics that communicated more human emotions with imagery instead of words, letters and squiggles. But, on another episode of Rogan's podcast, a similar idea came up with texting, but with a different interpretation. It was questioned if auto-correct and suggested responses may one day evolve so that we needn't have to text or message, until we will be simply watching our computers or phones have the chats we would - but are too lazy to type out. It's these two perspectives that outline just what The Narrator and Tyler are trying to escape. They don't want to live in a world of auto-correct and predictive messaging because it leaves them empty as is a mere extension of regressive rules of social conduct. Its predictive messaging that mimics not wanting being so impolite as to just ask a stranger for help, instead, take them for beers and wait for them to offer. The world feels easier with predictive messaging and another person offering instead of us asking, but we are taking ourselves out of the equation at our own expense. We aren't putting our true and nuanced emotions down on the page or screen. We aren't trying to conjure up new sentences, different ways of saying things, we aren't trying to do better, to have things be more personal and more real. To understand why real is important just look at emojis. A smiley face can work on many levels words may not, and with just one click, because they mimic what we are used to. We are used to looking at someone as they talk. When they say something we like we smile, we laugh. An emoji or a lol has to suffice on the phone, but all we're really trying to do is mimic real conversations so we feel the genuine emotions humans have been coded for. All this begs the question of why not just put down the phone and talk to someone? These are the exact questions Fight Club begins to probe. It wants true raw emotions and because the characters in this film are so tightly wound around themselves, the only way to get them out is through extreme actions and extreme emotions - fighting and the ensuing ecstasy of pain and triumph.

However, this devolves with the rise of Project Mayhem. But, we'll get into that later. First, it's important to understand the roots of the nihilism, the complete disbelief in belief, and anarchy, the singular belief in disorder, in this film. These two terms have their problems. You cannot be a true nihilist for reasons explored in the previous Thoughts On: essay. (link here). You cannot be a true nihilist because belief fuels perception and reality. You cannot be a true anarchist for the same reason. People perceive, and perception is simply noticing patterns. You cannot live a life without perceiving, nor experiencing patterns and a certain set of rules and structurings. However, there are healthy doses of nihilism and anarchy that we can all take. By suspending our belief in everything once in a while, we can gain perspective over the absurdity of the society we've created. We are born wanting to sleep, eat and fuck - and feel good, safe and comfortable in the moments between activity. Why, if this is what we all want, must we then work? Why, if this is what we all want, do we get married, struggle after sex, affection, love? These are great questions that allow us to assess the world we live in objectively. It's through a certain degree of nihilism that we can ponder, find out who we are and live by the rules we think make sense. For instance, why must we work? Well, yes, we all just want to be comfortable, but laptops, WIFI, heat and electricity don't just happen. You need to create and maintain these things, just like we need to create charts, move money around, market, produce art and so on. We must produce these things for others so we may also consume what we are not able to produce - and that's society. That's why we work. It might not be fun, but it makes sense. As for the second question of sex and love? Well, it's clear not everyone deserves our love, not everyone wants to be fucked, or have sex with another or every single person. We feel this way for evolutionary reasons, so we don't end up with mates who have bad genetics, or are horrible people. It's nihilism that makes society absurd, but we must not forget that nihilism is just a tool that raises us up for the purpose of perspective, so we can actually see the sense in a crazy system. The same may be said for anarchy. We live in a world that exist without any apparent reason or rhyme. Embracing this once in a while allows you to step back, look at the rules and decide if they make complete sense, if we want to be sending reams of emojis, if we want our computers to talk for us whilst we just watch, if we actually want to test the glass we feel we're made of with a good scrap. Again, this is what the first half of Fight Club sets up so perfectly, but in comes Project Mayhem...

Project Mayhem is perpetually enforced nihilism, it is systematised anarchy. This is what happens when you take the given concepts too seriously and act as if they are philosophies possible for people to live by. What we see with Project Mayhem is a group of guys from the Fight Clubs being taught to let go of rules to feel truth once in a while growing into men that do not believe in anything but Tyler. Project Mayhem becomes a cult. This cult believes in a dogmatic hierarchy, it believes solely in Tyler and what he believes. That's not nihilism - you're not supposed to believe in anything. However, professing you're a true nihilist leads to this. The same can be said for anarchy. The men working under Tyler aren't true anarchists because they have a leader, they are doing what they are told, they have rules, they support control. This is what leads to the final irrational bombing. But, the contradictive failure of Project Mayhem is best exemplified with the death of Robert Paulson.

He dies on an operation, getting shot in the head. The men's first reaction here is that the cops are pigs, that it is there fault alone. But, The Narrator is forced to ask: what did you think would happen!? It's at this moment that we realise the sheer mindlessness of these supposed anarchists and nihilists. Anarchy and nihilism affords the opportunity for perspective and enlightenment - only if you utilise it well. They came into the project to find out who they are, to find their independent and true self. But, it's chanting 'his name is Robert Paulson', a name given in death, that it's made painfully clear that the purpose these lost postmodernists are so desperately searching for, has disappeared within themselves - and that they buried it. They are fighting for purpose, a purpose only felt when dead. What the fuck is the point of that!? There simply isn't one.

What's also poignant is Marla. We mustn't forget that Marla is ultimately the crux of this film. She is what triggers Tyler and she is what The Narrator hides from. She is a person on his level that can help him through his own bullshit. A very important scene that comes midway through the film is one that mirrors the first fight The Narrator and Tyler have. As said, before the fight and after the beers, The Narrator is forced to actually ask Tyler if he can stay over. What this achieves is truth, it solidifies the relationship between The Narrator and Tyler - and is also the driving mechanism of Project Mayhem that brings all the men that it does together. But, during one of their many morning meetings Marla and The Narrator talk, but, as always, The Narrator cannot be honest with the only person he probably needs to be honest to - Marla and ultimately himself. When she tries to push him to talk about himself (Tyler) and her, he backs away from conversation, saying he's mot afraid, but in the end simply mirrors Tyler's words with: this conversation... this conversation... is over... BANG (shuts door)... is over. What this cites is The Narrators inability to be truthful when it truly matters. And just like the Project Mayhem goons blaming the cops for Paulson's death, The Narrator blames the world for his problems. What's horrifying is, like his goons, he has blinded himself to truth. He attributes everything shitty and contradictory that he does to Tyler - as if he's a different person. This brings us toward revelation pretty quick. The significance of The Narrator realising he is in fact Tyler comes with his sudden humanity and surge of morality. He sees that putting men in danger, feeding them lies of anarchy and nihilism isn't helping himself or them. And so he has to turn back to the beginning where he started to find truth in beating himself up. He fights Tyler, he fights with open eyes and wins, gaining his own personal independence and a hand to grab his...

... because, in the end, Fight Club is a romance. It's a search for love and personage in oneself and hopefully with someone standing by your side. Sounds pretty soppy for a film called Fight Club, huh? But, that's the truth. The truth is that The Narrator, much like us all, is an emotive creature. He feels happy, sad, lonely, lost. This changes his perception of self, and to deal with that, he figures he needs to change the world. But, with notions of nihilism and anarchy, The Narrator loses all sense of responsibility. That's why Fight Club is a cautionary tale. It's great to rebel, to question, to want change, but only if you hold in the back of your mind a constant reminder of your own personal responsibility. You should stay true to the idea that our actions are often towards personal growth - especially the pre-planned and questioned ones. But, you should also remember you ultimately want to eat, sleep and fuck - all whilst being happy, safe and comfortable in the moments between - and that's all. The 'moments in between' are the existential focus of one's life, they are only managed with open eyes, with a concept of responsibility - and it's what will hopefully stop you from having turn the gun on yourself whilst blowing up the world to get a fresh start. With perception meeting the reality through the senses our bodies hold, we must remember that we are a tool, but a tool that gets to exploit the system of reality. It's thus then ultimately true that control is the epitomal fantasy in a reality without free will or actual answers, where we are not omnipotent, all knowing, all powerful. This leaves us the only response of trying to control the fantasy we live in, not the world or reality as that is simply impossible. I've said it before, I'll say it again...

Cinderella - A Psychological Thriller

This is, without a doubt, Disney's best film. It's one of my favourite films of all time. Moreover, it's probably one of the greatest stories put to film. And, yes, this is the also the film I postponed so I could write about 50 Shades Of Grey, but, like I said, I was in the mood for something not so healthy, something that wasn't good for me, but in the end probably wouldn't kill me. Anyway, enough of 50 Shades. I've been meaning to do this film for a long time and, if you're familiar with the blog, then you may have heard me talk about it before. But, we'll return to that in the end. Right now, I just want to jump into things, so let's go. Cinderella is about hope. But, more than that, it's about hope as an act, hope as a mind set. The end goal here is for me to dispel the argument that 'And they lived happily ever after' is bullshit. But also, I want to demonstrates the intricate allegory that Cinderella is, explaining a film you probably didn't think needed much explaining. To do this we'll simply run through the film, start to end, defining metaphors and seeing what they mean in respect to Cinderella's journey here. Oh, we'll also be breaking down a lot of plot holes, but also convoluting the narrative as a whole, so, heads up, head down, whatever it is, let's get to work.

With the intro we are given the song that outlines a theme of romanticism in the film, which is a segue toward hope and Cinderella's opening song. But, before that we get a bit of information about the kingdom and Cinderella's past. Her father was a widower, but died when she was young - the point at which her step-mother revealed her true colours, forcing Cinderella to be the family's scullery maid. The most important detail of this back story is this one frame:

This is our way into the depths of this film as a psychological thriller. To get into this, I advise you watch the intro quickly, paying close attention at the 0:40 second mark. LINK HERE. It's at that 43 second mark that we hear of a 'mother's care' and simultaneously see a few birds flit on screen (you can see one in the picture above). What I'm trying to establish here is a link between animals and people - specifically Cinderella's perspective of people. It's in her mind, and as the freeze-frame demonstrates, that Cinderella would attribute the memory of her father to his horse and dog, Major and Bruno. Moreover, she attributes an idea of her mother to the symbol of a bird. Now, as you know, animals play a huge role in this film with almost all direct conflict stemming from interactions between the mice, birds, cat, dog and so on. But, we aren't just watching filler in a 70-odd minute film with these scenes. What we are watching is Cinderella's memory and projections of self conflicting. The majority of this movie is just a presentation of Cinderella's will. It's her losing hope, time and time again, but persevering, rising against the people in her life. So, to explore deeper, we'll take this one animal at a time.

We'll start with Major as we've already touched on him. He is the personification of Cinderella's memory of her father. He represents the composed and devoted aspects of his character. We can also infer with the horse that maybe Cinderella's father was apart of the army, hence, Major. This reinforces the aspects of composure and control. Moreover, these characteristics all act as lessons to Cinderella. These reminders of his character make her days easier, allowing her to wake up and almost find a friend in him as to go on.

Bruno. Also a representation of Cinderella's father. This is both his playful and more emotional side, that at times lacks the composure Major does. We see this in the fact that he's a dog that hates Lucifer - the cat. We'll come to back to this in a while though. The last detail to recognise about both Major and Bruno is their age. Both are a little groggy, a bit lazy - Major even has grey hair. This shows that they have not only grown up with Cinderella, but almost grown up as her father would. If he were alive 10/15 years down the line (from the beginning) he too would be a bit groggy and even have grey hair.

The birds. Ok, I know I implied that these represent Cinderella's mother, but because there are so many of them, they don't adhere to the rule as strictly as singular characters such as Bruno or Lucifer. Fundamentally, birds are a distant idea of a mother with Cinderella. This is best understood via the mornings. The birds wake up and tend to Cinderella, who is still a teenager (19) but also quite the tortured one. Moreover, they sing with her, something that we'll come back to in a while which is very important. Overall however, birds represent both an idea of devotion and an idea of freedom. They are linked to Cinderella's mother because she is dead, but still a guiding force as she is probably the woman Cinderella aspires to be. The birds are then an idea of female maturity.

Ok, this guy. This is Cinderella's projection or idea of her stepmother. It's important to recognise here that this is not a direct representation of her, but Cinderella's way of dealing with the oppressive, golddigging. bitch. When characters such as the mice interact with Lucifer, we are seeing the inner workings of Cinderella's mind. It's the fear, the hatred, the disdain, she has for the stepmother that is being fought with her own personal character. Before moving on though, there's quite a lot we can infer from Lucifer. Also, it's here that religious undertones are implied, as you could recognise with the name Lucifer. Lucifer was of course a fallen angel. His fall from God's side may parallel the change, the undressing of the stepmother's true colours when Cinderella's father died. This then implies that Cinderella's father was God (I know, sounds a little reaching). But, to ground this idea, what's happening here is simple. Cinderella is being compared to Jesus. You can understand this in her ethics of forgiveness, self-control and general humbleness. The religious undertones, however, under my interpretation, don't go much further than this though. In short, Lucifer is a douche, just like the stepmother,

Jaq is Cinderella's primary projection of self. Jaq encapsulates her tenacity, mischievous nature, confidence and personal strength. Jaq is the wise guy, the one willing to fight Lucifer, to lead the pack. We don't see this side of Cinderella much outside of Jaq, but make no mistake, it's Jaq, Cinderella's hidden bravery, that gets her through life, that allows her to hope, dream, wish.

Gus, for all his innocence and naivety is the unfortunate projection of Cinderella's perspective of self. To understand this, we have to recognise the importance of his introduction to the film. It's after waking up that Cinderella finds Gus in a cage, a trap probably set out by the stepmother. This means that this projection of Cinderella's self is dictated primarily by anxiety, by the stepmother putting her down for these numerous years. Gus' two key characteristics are naivety and greed. The naivety feeds into Cinderella's will to fight, to rebel. This is however encapsulated by Jaq already. What this means is that Cinderella is starting to lose hope, she's starting to criticise herself with Gus. This is why it's important she nurtures and looks after him as not to let her defeat herself. The aspects of greed are also linked into Cinderella's hopelessness, her growing self-defeatist attitude. Greed with Gus is wanting too much and getting in trouble. In this respect, this...

... is Cinderella's inner commentary on romance. Is wanting to go to the ball too much? Do I deserve better? Am I being ridiculous? These are all questions in her head. But, they aren't entirely negative as they do get her out of trouble. You could argue that if Cinderella did spend more time in picking up her glass slipper, like Gus did here (he picks up a grain that another mouse abandons - just as Cinderella does the slipper) she'd be stopped by the prince and forced to show her true colours. I agree, this side of her represents her lack of confidence in self. But, it is, however, important that she does face her stepmother, that she does accept herself, in the end of the film. So, this aspect of her isn't all that bad. The last thing to say about Gus is that whilst he's a little ditsy, so is Cinderella. But, that, again, isn't all that bad.

The rest of the mice are also projections of Cinderella's self. However, they aren't too specific. What they represent is Cinderella's capacity to work hard, persevere, but also collect herself. This is incredibly important in the dress making scene, but, we'll come to that later.

Ok, so now we understand who Cinderella is. She is an amalgamation of all these characters discussed. She's not just meek, naive and full of hope. She fights for her revelation in the end. This film is, as you can now see, a psychological battle between Cinderella's me, myselves and Is. Knowing this, let's move onto to the first real scene of the film to establish themes. The two main ideas or themes in this film are Time and Hope. This is perfectly captured by Cinderella's (click the picture to watch) opening song:

I've got to say that this is my favourite Disney song of all time and one of the greatest scenes ever. It has a perfect balance of tone, atmosphere and feeling that perfectly sets up the film, imbuing the audience with hope, not just telling them of it. Now, where the clip ends is where our biggest theme comes in. The clip ends just before the clock strikes, introducing an idea of time and reality. When you juxtapose this with Cinderella's A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Aches, you end up with a debate very similar to one I covered with The Matrix - Is It All Really That Bad?. Cinderella's problem is that her reality is controlled by time, that her world is controlled by her stepmother. This is why hope is so important. Hopes, dreams and wishes are the same thing. They are an idea of imagination - which also makes this being a psychological thriller with a myriad of talking animal projections all the more necessary. Cinderella is incredibly dependant imagination as she cannot change reality, she doesn't see herself as having the power to. Whilst there are great messages in films like Tangled or Frozen about women taking action and physically fighting against adversity, I think Cinderella holds an equal, even better message. The criticism of the old Disney films revolves around damsels in distress. Cinderella is not a damsel in distress. She fights her own personal and mental battle to gain the confidence to seek out love and change her life. This doesn't mean she needs a man to get by. This most definitely isn't the message of the film. The message is dependant on recognising that Cinderella wants love. She wants not needs a relationship and love (as most human beings do). This means that the physical fight here isn't necessary as this is a film about changing on the inside as to cope with externals. Cinderella actually fills gaps of other empowering films such as Frozen and Tangled. Frozen and Tangled are about acting with confidence as a woman. Cinderella is about finding that confidence. This, again, throws back to the Matrix post. Saying Let It Go is a great message, but actually doing that is incredibly hard. You need the message of hope captured by Cinderella to complete the picture painted by the likes of Frozen and Tangled. And it's with the opening song that this seed of philosophy is planted. In short, Cinderella asserts to herself that she must hang on, that she must continue to persevere with each and every morning. And it's after this that she counteracts the point with Gus. She begins to see herself as trapped. But, this is exactly what catalyses the movement of the narrative and her life toward action.

After this we meet the other characters (as discussed) with one pivotal interaction with Bruno. I'm talking about the scene where Bruno dreams. Remembering now that this is Cinderella's idea of her father, what we are seeing is her dad being enraged by the idea of the cat, of the woman that betrayed him and tortures his daughter. However, Cinderella tells Bruno off, not only for hating the cat (the stepmother - and rightly so) but also for dreaming. This sounds hypocritical coming from a girl that just sang about dreams being wishes the heart aches. But, it's not. Her justification for this is that Bruno doesn't want to lose a warm bed. This is her comment to anyone claiming she's a damsel in distress. Yes, she in a bad situation, but this is also her home, this is where she belongs - and she has nowhere else to go. This is why it's important for her to stay, to psychologically battle with an idea of her stepmother so she may eventually overcome.

The next key moment after this is the end the segment with Gus, Lucifer and the cups. This not only demonstrates how Cinderella is trapped by the idea of her stepmother, but introduces an idea of probability into the film which becomes all the more important as we progress. It's with the scene between Gus, Lucifer and the doors that an idea of all or nothing, which is prevalent in the film, becomes obvious. In short, Gus is saved by there being three cups. They prevent Lucifer finding him at first. However, the cups are then taken into the rooms, where everything simply turns into a waiting game. And so, Lucifer waits until one of the girls scream and Gus comes running out. He grabs him, but Cinderella puts a stop to it. After Cinderella gets into trouble, we cut to the castle where, just like with Gus and Lucifer, the King decides to wait, to put all his eggs in one basket to have his son fall in love. These given ideas of probability, all or nothing and putting all your eggs in one basket are pivotal in Cinderella. In short, the film argues that there is always opportunity out there. The odds can be stacked against you, but you have to take the opportunity, assert yourself in the situation. Just like Gus inevitably being caught is stopped by Cinderella, the Prince inevitably finding a woman to marry has to be intervened by her too. Cinderella must take hold of opportunity. This is the film's rationale against the idea of Cinderella finding true love being an ex-machina. However, that doesn't mean the film isn't romantic and doesn't take liberties, but, despite elements of luck there is a solid message in Cinderella you can take seriously: grab the bull by the horns essentially.

The next key scene we come to is before the news of the ball is delivered. What we're talking about here is the singing lesson. It's through comparing Cinderella to Drizella and Anastasia that we can recognise the importance of the opening song and also the birds. A nightingale, the bird the song they sing is about, is a symbol in literature that represents sorrow and beauty. For the nightingale to sing is almost a test, it's a question of character. To understand this, just look at Drizella and Anastasia. They can't sing, aren't very attractive and aren't very nice people. They have no song worth hearing in other words. Cinderella on the other hand is not only beautiful, but can sing and is a fair, composed person. The importance of beauty here is all linked to jealousy and the stepmother. It's because Cinderella is beautiful that she primarily dislikes her. This song thus captures the irrational attack on people from a position of powerlessness or ineptitude. In other words, the stepmother drags Cinderella down because she is all that Cinderella is not. Most importantly the stepmother lacks self-control or self-respect. This is what kills her, and is exactly what allows Cinderella to overcome her. This means that the birds being connected to an idea of Cinderella's mother is her accepting that she shouldn't hate herself for the same reasons her stepmother does. It's the birds, that can sing, that teach her to be humble, patient, controlled - all ways in which she may be imitating a memory of her mother. It's by tracking this that you can see Cinderella's growth as a woman throughout the film, and all on a psychological level.

Ok, so after this we get the dress making scene. This seems like an irrational plug to get the film where it needs to be in the end - Cinderella with a dress and at the ball despite the chores she has to do. This, as you could infer by now, isn't a plot hole though. The mice and birds all represent Cinderella's perseverance. What this implies is that she found the time, that she had the tenacity to steal the beads, the sash and not do house work (which she doesn't have to do as it's done already - her stepmother told her to do it all again). The reason why this wasn't shown may be down to preserving the image of Cinderella's character (not showing her steal), but more than this, is this not a much more cinematic and entertaining way of telling a story? There's just miles more depth in having representations of Cinderella's psyche do the work, persevere and so on. You externalise emotions, cinematically conveying feelings and mental growth. But, having made the dress, having cheated her way toward the ball, Cinderella's caught out. The malicious nature of the stepmother overcomes her again, tearing away all senses of hope. It's here where we are introduced to the final projection of Cinderella's imagination:

The fairy godmother is the epitome of hope, is the last reserve Cinderella has. This is where she turns in her darkest moment. I quote the movie here: 'If you lost all your faith, I couldn't be here. And here I am.' These are the words of the fairy godmother that solidify the idea that we are seeing projections of Cinderella's imagination. It's faith that manifests the fairy godmother. Faith is belief - all products of the mind, of hope, dreams, imagination. What's also key to recognise here is an aspect of childish hope. By this I mean the concept of a fairy. Cinderella has to regress into her childhood to find the last inklings of hope and dreams. This is what gives her the means to go on - naivety. What this makes clear is that sometimes you have to blind yourself to go on. You have to ignore probability, reality, reasoning to physically get through the improbable. However, coming back to the idea of childhood, we can now justify the lyrics:

Salagadoola mechicka boola bibbidi-bobbidi-boo

Put 'em together and what have you got

bippity-boppity-boo

Salagadoola mechicka boola bibbidi-bobbidi-boo

It'll do magic believe it or not

bippity-boppity-boo

Salagadoola means mechicka booleroo

But the thingmabob that does the job is

bippity-boppity-boo

Salagadoola menchicka boola bibbidi-bobbidi-boo

Put 'em together and what have you got

bippity-boppity bippity-boppity bippity-boppity-boo

The majority of this is nonsense, just as a kid's chant or song of this nature would be. Take away sense and reasoning and just believe, then life becomes easier. That means that the metaphor of this scene is that Cinderella fixed some kind of dress for herself and went to the ball - she persevered. What you then have to infer is that the dress is also a metaphor. This is all a given if you can accept that the animals are mere projections. The mice, Bruno and Major all transform, indicating a boost in Cinderella's confidence. In short, she's using the idea of her father as guidance - he acts as a chaperone. But, staying with the dress, what we are seeing is hope toward social transcendence. This is also why the glass slipper is the most important symbol in the film. The dress and slippers are a facade that gives Cinderella confidence, but they are also the true manifestation of her hope. The shoes are glass, however, because the hope, the dream of Cinderella overcoming everything is fragile. Nonetheless, she meets the prince, she does dance, and most importantly, she keeps the slippers. This implies that what remains after the night is Cinderella's confidence. She manages to keep her dream alive, she is able to hold onto an idea of love.

It's now that we can jump to the end of the film. Here the figurative entrapment of Cinderella becomes literal. To fight this she needs a bit of help from her projections. It's Gus and Jaq, the two conflicting ideas of her self (the good and bad, or the better and worse) that have to work together to get the key. Opening the door isn't that easy though as the domineering idea of the stepmother steps in. However, lessons, or ideas of Cinderella's parents finally come into effect. First it's her mother, then it's her father, who gets to exact his revenge on the woman that betrayed them. This kind of means that Lucifer dies and Bruno (the father) killed him. I mean...

... but, don't worry. This isn't literal. Cinderella merely relinquishes the idea of her stepmother from her mind. Even if the cat dies, so what? He was an ass. I don't like cats, what can I say? Anyways, meanwhile, downstairs the glass slipper is being tried on by Anastasia and Dizella. The key plot hole here is that the slipper should be able to fit an awful lot of girls in the kingdom. This is why recognising it as a metaphor is so important. It's a metaphor for Cinderella's virtue, Cinderella's strength, hope and resilience. This is what is unique to her. This is what no other woman in the kingdom has. This is what the prince is really looking for. So, in the end, the one slipper can break, all of Cinderella's faith and hope crushed by the stepmother's jealousy yet again, but, it's just not enough.

She has the other shoe. It's then because of this that she can live happily ever after. Why? How? Happiness, just like hope has been thoroughly demonstrated as being a mindset that allows you to act. When you've been through what Cinderella has, when you've been through massive psychological duress and pressure, but made it through by the strength of your own will, you've proved your ability to cope. This is the true message encapsulated by the 'happily ever after'. Cinderella has learnt a life changing lesson. Because she is capable, she will ensure she lives that happily ever after.

Fight Club - Nihilism, Anarchy And I

An insomniac runs into a soap salesman.

We've all seen it. And so the warning is pointless, but, SPOILERS. Tyler Durden is a projection of The Narrator's screwed up mind. With that said, this is a movie entirely about self-destruction sourced from a simple lack of identity. Fight Club is a movie much like The End Of The Tour, but more extravagant with an exuberant, boisterous and hyperbolised style, movement and characterisation. This is then a movie that is, at its core, pretty petty. However, the truth of this is presented in a manner you can take seriously, in a manner you don't feel you must mock. So, the core of Fight Club is of a man that is simply not happy. To combat his depression he wallows in it, but when he can no longer feed off his own bullshit, he decides to hit self-destruct. His self-destruction through Tyler is actually tantamount to us not being able to take the plights of this movie (or something like The End Of The Tour) seriously. The narrator knows his problems are pretty pathetic, he knows that going to the dozen support groups he has no place in joining is pitiful, pretty scummy and completely self-absorbed. It's with Marla that this narcissistic essence of his self becomes unbearably upfront. This is what triggers Tyler. Tyler is nothing more than a way for The Narrator to punch himself in the face and stuff Marla without having to recognise the fact that he is both pathetic and could maybe push a way out of his depression. The paradigm of this film is then all about a reflection of self. In the very beginning, The Narrator is forced to look in on himself and see nothing. He stays up night at day, simply wanting reprieve. He hates his job. He hates the system he is apart of. He wants out.

To understand The Narrator's position you simply have to see him in an empty room. There is a door and it's unlocked. The Narrator wants out. What does he do? He walks to the door, pulls it open and leaves, right? Ok, but what if The Narrator can't walk? The door is now shut in spite of him, his efforts, his need to translate thought to physical actions are fruitless. It's now that we see his depression, his insomnia, his debilitating lack of perceived self. He sees himself as empty and so is powerless to leave his unlocked room. What happens if, in exchange of locking the door, we give The Narrator a friend with a bomb? He still wants out, but he's not moving. Why not let the friend destroy the room around him as he stands? This is the entire narrative of Fight Club. The Narrator senses a vacuous hole beyond the shell of his skin, and this makes him feel like absolute shit. To escape this, he projects the shit onto the walls around him. He then decides that if he wipes the walls clean, maybe wipes them away completely, the shit inside him will be gone too. What we see here is a cushion of nihilism being popped by a pin of anarchy. The Narrator doesn't believe in himself and so he doesn't believe in the world. He decides he wants to lose control, he wants to play with his internal self-destruct button, and then he decides the world's self-destruction also needs to be hit. This translates to Tyler's plan to destroy all monetary and capitalists aspects of society instead of The Narrator searching within himself for a new beginning. This trait of The Narrator and Tyler is immersed in a plea to the world to stop letting them (him) destroy themselves (himself). In short, it's working a boring job for money and to simply accumulate things, that are so easy to do, just like watching TV, living a safe, quiet life by everyone else's rules. However, we choose to live the easy life, to indulge in shit that's not good for us. Is it right that the world then be labelled corrupt? Is it right that we then think the system needs to change? Does it make any sense that what we feel in side is irrevocable attributed to the world around us along with blame and consequences to come?

This is a question Fight Club begins to ask. However, this is not the last interrogative given by the final image of the film...

What this image caps off is the end of a cautionary tale. The Narrator and Tyler alike, no matter how enjoyable they are, no matter how convincing their case for anarchy feels, are (somewhat inadvertently) liars. Don't get sucked into what they preach. That is not what the film is about. As said, this is a film about finding yourself. It's subsequent commentary then comes with how people tend to approach this perpetually distancing peak that is ultimately insurmountable - knowing just who you are. Again, this is a film about finding yourself, about finding your own individuality, and it starts with The Narrator breaking away from his shirt, tie and suitcase by beating himself and friends up for a laugh, to actually feel, to experience physical truth. It's the beginning of the second act where the nihilistic and anarchistic elements of this film teach lessons that actually help The Narrator. What The Narrator and Tyler start off doing is simply chipping away at the hatred they have for themselves. They feel weak and pitiful and so they ask themselves just how weak and how pitiful they are. They test and find this out with Fight Club. And it's, as Tyler says, Fight Club that is truth, that isn't bullshit and lies. What's bullshit is The Narrator's boss being a better person or having more power than The Narrator just because of a title. This social hierarchy is what we all experience every day. It's having to be polite, having to be passive aggressive, having to not ask someone who believes they are better than you to actually prove it. It's the monetary and capitalist aspects of society as presented by the the first two acts and all of the workplace scenes that demonstrate how we live in a society where we fight with metaphors, with implimence, with intangibility and hidden agendas. And the rules of this world remained undefined as we simply aren't able to talk about them. And it's that there that should be ringing all the bells. We all know it:

"The first rule of Fight Club is: you do not talk about Fight Club. The second rule of Fight Club is: you do not talk about Fight Club."

These rules are a massive fuck you to the way we operate in a civilised society where we have to be passive aggressive, we have to be fake and lie - and never talk about that fact. The first two rules are then a dare to actually say who you are, to actually say what you feel you must not, to talk about Fight Club despite authority. This is a paradigm repeated throughout the film. In fact, it's after Tyler and The Narrator have their beers over The Narrator's apartment blowing up that Tyler demands The Narrator actually ask if he can stay at his place. This is the best example of social conduct being thrown out the window in search of honesty. Tyler knew what The Narrator wanted to ask. The Narrator knew that Tyler knew. Still, he keeps his mouth closed as it's the polite thing to not be upfront, as he didn't want to force a yes, or hear a no. These touch and go rules of society keep us from truth, keep us from being honest with one another and ultimately separate us all. I don't believe this a universal truth, and I don't think we should be unconditionally honest. But, more honesty in our world is something that wouldn't go amiss. This is a concept explored by another film...

... so maybe I'll save that talk for another time. Nonetheless, honesty is all Fight Club represents, is all Tyler and The Narrator are in search for in the first half of this movie. The subsequent rules of Fight Club reinforce this:

"Third rule of Fight Club: if someone yells “stop!”, goes limp, or taps out, the fight is over. Fourth rule: only two guys to a fight."

However, this devolves with the rise of Project Mayhem. But, we'll get into that later. First, it's important to understand the roots of the nihilism, the complete disbelief in belief, and anarchy, the singular belief in disorder, in this film. These two terms have their problems. You cannot be a true nihilist for reasons explored in the previous Thoughts On: essay. (link here). You cannot be a true nihilist because belief fuels perception and reality. You cannot be a true anarchist for the same reason. People perceive, and perception is simply noticing patterns. You cannot live a life without perceiving, nor experiencing patterns and a certain set of rules and structurings. However, there are healthy doses of nihilism and anarchy that we can all take. By suspending our belief in everything once in a while, we can gain perspective over the absurdity of the society we've created. We are born wanting to sleep, eat and fuck - and feel good, safe and comfortable in the moments between activity. Why, if this is what we all want, must we then work? Why, if this is what we all want, do we get married, struggle after sex, affection, love? These are great questions that allow us to assess the world we live in objectively. It's through a certain degree of nihilism that we can ponder, find out who we are and live by the rules we think make sense. For instance, why must we work? Well, yes, we all just want to be comfortable, but laptops, WIFI, heat and electricity don't just happen. You need to create and maintain these things, just like we need to create charts, move money around, market, produce art and so on. We must produce these things for others so we may also consume what we are not able to produce - and that's society. That's why we work. It might not be fun, but it makes sense. As for the second question of sex and love? Well, it's clear not everyone deserves our love, not everyone wants to be fucked, or have sex with another or every single person. We feel this way for evolutionary reasons, so we don't end up with mates who have bad genetics, or are horrible people. It's nihilism that makes society absurd, but we must not forget that nihilism is just a tool that raises us up for the purpose of perspective, so we can actually see the sense in a crazy system. The same may be said for anarchy. We live in a world that exist without any apparent reason or rhyme. Embracing this once in a while allows you to step back, look at the rules and decide if they make complete sense, if we want to be sending reams of emojis, if we want our computers to talk for us whilst we just watch, if we actually want to test the glass we feel we're made of with a good scrap. Again, this is what the first half of Fight Club sets up so perfectly, but in comes Project Mayhem...

Project Mayhem is perpetually enforced nihilism, it is systematised anarchy. This is what happens when you take the given concepts too seriously and act as if they are philosophies possible for people to live by. What we see with Project Mayhem is a group of guys from the Fight Clubs being taught to let go of rules to feel truth once in a while growing into men that do not believe in anything but Tyler. Project Mayhem becomes a cult. This cult believes in a dogmatic hierarchy, it believes solely in Tyler and what he believes. That's not nihilism - you're not supposed to believe in anything. However, professing you're a true nihilist leads to this. The same can be said for anarchy. The men working under Tyler aren't true anarchists because they have a leader, they are doing what they are told, they have rules, they support control. This is what leads to the final irrational bombing. But, the contradictive failure of Project Mayhem is best exemplified with the death of Robert Paulson.

He dies on an operation, getting shot in the head. The men's first reaction here is that the cops are pigs, that it is there fault alone. But, The Narrator is forced to ask: what did you think would happen!? It's at this moment that we realise the sheer mindlessness of these supposed anarchists and nihilists. Anarchy and nihilism affords the opportunity for perspective and enlightenment - only if you utilise it well. They came into the project to find out who they are, to find their independent and true self. But, it's chanting 'his name is Robert Paulson', a name given in death, that it's made painfully clear that the purpose these lost postmodernists are so desperately searching for, has disappeared within themselves - and that they buried it. They are fighting for purpose, a purpose only felt when dead. What the fuck is the point of that!? There simply isn't one.

What's also poignant is Marla. We mustn't forget that Marla is ultimately the crux of this film. She is what triggers Tyler and she is what The Narrator hides from. She is a person on his level that can help him through his own bullshit. A very important scene that comes midway through the film is one that mirrors the first fight The Narrator and Tyler have. As said, before the fight and after the beers, The Narrator is forced to actually ask Tyler if he can stay over. What this achieves is truth, it solidifies the relationship between The Narrator and Tyler - and is also the driving mechanism of Project Mayhem that brings all the men that it does together. But, during one of their many morning meetings Marla and The Narrator talk, but, as always, The Narrator cannot be honest with the only person he probably needs to be honest to - Marla and ultimately himself. When she tries to push him to talk about himself (Tyler) and her, he backs away from conversation, saying he's mot afraid, but in the end simply mirrors Tyler's words with: this conversation... this conversation... is over... BANG (shuts door)... is over. What this cites is The Narrators inability to be truthful when it truly matters. And just like the Project Mayhem goons blaming the cops for Paulson's death, The Narrator blames the world for his problems. What's horrifying is, like his goons, he has blinded himself to truth. He attributes everything shitty and contradictory that he does to Tyler - as if he's a different person. This brings us toward revelation pretty quick. The significance of The Narrator realising he is in fact Tyler comes with his sudden humanity and surge of morality. He sees that putting men in danger, feeding them lies of anarchy and nihilism isn't helping himself or them. And so he has to turn back to the beginning where he started to find truth in beating himself up. He fights Tyler, he fights with open eyes and wins, gaining his own personal independence and a hand to grab his...

Control, the fantasy; control the fantasy.

Before Sunrise - Talking Heads

A couple walk through the streets of Vienna, talking through the night util morning.

Simple and perfect, though maybe a little pretentious, Before Sunrise is a tremendous film that I love to revisit every now and then - just as much as Sunset and Midnight. And this is certainly one of those films, alongside a lot of Linklater's early pictures, that has such a powerful capacity to inspire anyone interested in film. You find the same thing with Kevin Smith's Clerks, but, just before Smith was Linklater, one of the first and brightest filmmakers to come out of the independent cinema movement of the 90s. And so it's Linklater's Slackers, Dazed And Confused and then Before Sunrise, which all of course followed each other, that we see tremendous films that serve as definitions of 90s independent cinema and that say to anyone interested in films: if you're dedicated, young and a bit of a delusional fool, you could (hopefully, maybe, possibly) make a good film.

However, the simplicity of Before Sunrise not only implies to aspiring filmmakers that cinema can be a tangible, real thing if they pursue it, but this simplicity is also at the heart of all that works with this movie. In such, the best way to define Linklater's approach in films such as Slackers and those apart of the Before Trilogy is 'character realism'. Realism, depending on who you ask, can mean various things. However, the most basic definition would imply that realism is an appeal to the reality of the world through every element of an art form, in our case, cinema. Some of the most iconic expressions of realism then came out of post-war Italy in the 40s and early 50s. However, looking at films such as La Strada, Bicycle Thieves and Rome, Open City, there doesn't seem to be a clear relationship with Before Sunrise. A lot of this has to do with context, of course. But, the heavy genre elements, the romance and focus on chance and coincidence, in Before Sunrise play against its natural acting style and use of real locations. So, whilst you could certainly argue that Before Sunrise is a realist film, I think it is best to look at it as one that attempts to conform to the reality of its characters, hence, 'character realism'.

So, it is then thanks to to Linklater, his co-writer Kim Krizan, as well as Delpy and Hawke, who not only play the characters, but where a significant part of their development, that there is such an immense sense of verisimilitude conjured as we watch Celine and Jesse walk the streets of Vienna. And it is because there seems to be no overwhelmingly obvious cinematic illusion dictating these characters' actions and thoughts that, as we are trapped with them, as they are simultaneously trapped with one another, that our narrative cage becomes a very comfortable one. One of the most profound implications of this film then reveals itself to be cinema's ability to slot an audience into a conversation; just like a great conversation can have us lost in time until we realise that it's 4 in the morning, so, seemingly so, can cinema. However, with that said, I don't think that this statement, nor the experiment that this film seems to be, is a pure one. In such, there is of course editing in this movie - it isn't a 6 hour long shot. What's more, the various locations that Celine and Jesse travel through do add hints of spectacle and attraction as an aside to the bond between the two characters. So, again, I wouldn't say that this is a purely realist film - nor would I suggest that such a thing would likely work, after all Warhol's experiments with realism represent an anti-film not worth more than 5-10 minutes of attention.

The true beauty of Linklater's character realism then lies in its non-realist attributes. In such, what really makes Before Sunrise work is the fact that it is 'a film by Richard Linklater'. And whilst there is a debate to be had on the idea of an auteur as the singular voice of a film, there is a recognisable tone and measure to Before Sunrise that can be found in the rest of the Before Trilogy, Slackers, Dazed and Confused, Waking Life as well as elements of Boyhood, Everybody Wants Some and School Of Rock. And what binds these films is, of course, Linklater. So, when we return to the voice of Before Sunrise, we find this to be the fourth-wall-breaking, non-realist glue that makes this film so tremendous. In such, much like with the films of Tarantino, there is a sense that Linklater is unambiguously talking to us through a veneer of cinema. What then defines the character realism in Before Sunrise is the fact that, though these characters seem individual and real, they also seem to be talking through the same mouth; what we may consider to be Linklater's. Again, I certainly think this can be disputed because of the highly collaborative nature of this film, but, it certainly feels like a writer (whether that be an individual or a collective term) is talking to us as opposed to two constructed people.

Returning to the idea that Linklater's early films are especially inspirational to aspiring filmmakers, I think the writer's voice that oversees these films has a lot to do with it. In such, art is often a selfish means of self-expression, or, as is suggested in this narrative, attracting love. To see and experience what seems like one man's voice and vision is what implies that anyone can make a film. (After all, all they need is themselves - and they're often available and at hand). However, there is more to this ominous and pervading writer's voice that seemingly appeals to audiences without aspirations in film. It is the presence of a familiar and welcome voice, one that unites characters, debates with itself, argues with itself and falls in love with itself, that lies as the heart of Before Sunrise, and, arguably, the indie film in general.

This is an idea that is, indirectly or not, commented upon in this narrative with the scene in which Celine and Jesse discuss people being 'sick with themselves'. People need escapism and entertainment not only to free themselves from their mundane reality, but their conscious shadow that they cannot seem to shake loose. And so it is film, T.V, books, theatre, music and other various forms of entertainment that distract our shadow, our unconsciousness and sense of self, and allow us, or at least what is left of us, to exist in another realm of consciousness. And in such, unlike what Jesse suggests, it then seems that we all often visit places that we've never travelled to, greet people we've never met and experience what we've never felt. After all, Before Sunrise is a perfect projection of this idea; we experience an implication of love, human bonds and attraction, all without getting on a train to Vienna.

The relation of this unconscious travel to a clear presence of a writer throughout a film like Before Sunrise concerns the manner in which cinema has us socialise. Just like there is a communal experience at the heart of going to a cinema and sitting in a pitch room to stare at a screen with a few dozen, maybe hundred, other people, so is there a communal experience in ingesting a film. In such, the experience of a story can be defined by an audience member and the storyteller; the content of the story can be considered latent and abstract. This is why hearing a writer's voice and feeling their presence through what are supposed to be individual characters lies at the heart of films such as Before Sunrise; the connection is not so much to an abstract idea of a character or characters, but to the storyteller. It's this idea that begins to express the ingenious, even profound, nature of Before Sunrise. This film isn't so much about realism and simplicity, but cinema acting as a voice for a filmmaker and a window of communication for an audience - all through the facade of character realism.

So, Before Sunrise is a very interesting film, one that has layers of realism and verisimilitude blending with fantasy, contrivance and disillusionment. I think this is what it manages so well, and so is the reason why it is such a tremendous film.

Lost In Translation - Existential Drama

Two lonesome married individuals meet and befriend each other in Tokyo.

Lost In Translation is an exquisite film, one that not only looks gorgeous, but is paced near-perfectly (one or two sequences drag a little) with such subtle, yet rich, characterisation. An in such, Lost In Translation falls into a class of film that often proves difficult to pull off. This is what we may refer to as an existential drama, a story that is entirely focus on the inner conflicts of our protagonists. However, instead of focusing on huge existential questions that snowball into intense drama, tears, hatred, destruction and decimation, Lost In Translation explores subtle, gnawing attributes of life that are difficult to talk about without being pretentious. This narrative is then about a lost sense of purpose as attached to relationships.

A crucial element of this topic that Lost In Translation does so well in handling is the hurdle of unattractive mundanity. In such, the existential problems of meaninglessness that can pervade the lives of the well-off, which are depicted in this narrative, not only seem trivial when we consider the more dire circumstances that millions of people face every day, but they also have the potential to be common in all people. This leaves this topic of meaninglessness as one that is unattractive, relative to more pressing conflicts in the world, and one that is pretty banal or mundane. However, because of the universal nature of this problem, shouldn't it be one that we all relate to despite the fact that there are greater problems in the world? I suppose the answer is maybe, and this film proves that there is a manner in which these issues can be articulated without seeming petty. But, that pettiness is difficult to manage - which is what leaves this film such an impressive one. This is because, regardless of the universal nature of meaninglessness as an existential problem, there is very little to be said about it. We see this throughout Lost In Translation through the sheer fact that the deep-rooted problems that Charlotte and Bob face are never really discussed or explored in much depth, only ever displayed. In turn, we never see Bob argue with his wife about the fact that he feels isolated and would somehow like to work with her to find a better place and sense of purpose in their family circle. Moreover, we never see Charlotte discuss the fact that she would like to be of greater significance in her husband's life with him.

A significant part of Lost In Translation is then this articulatory and existential constipation, one that leaves our characters wordless and, for lack of a better word, lost in the face of their problems. And I believe this perfectly outlines why this film is called 'Lost In Translation'; not only are these inner conflicts lost on the channels of communication somewhere between husbands and wives, but purpose itself has not revealed itself in the lives of all concerned. What Lost In Translation is then indirectly about is the lack of an articulate and meaningful structure at the foundations of our character's lives. Without much of a religious, philosophical, ideological or spiritual crutch, all of our characters then have no idea what to do with their marriages, nor do they know how to begin managing their lives. And this is certainly one of the most daunting issues that people seem to be facing in the modern age - and in a different capacity to eras beforehand. Whilst we have a diverse world-wide network of communications, we often use these innumerable channels for meaningless folly. Consider, for example, the role that T.V has played in society over the past 60+ years. Never has it been widely considered a box of learning and development, rather, entertainment (despite interesting pieces of culture, the news and documentaries that find their way onto television). We find a similar thing with the internet. However, whilst the internet is primarily used for banal things, it is an incredible tool that we all often use for greater purposes - whether it be to simply Google something you didn't know or to commit to developing yourself and life somehow over the internet. So, whilst there is meaning and higher purpose to be found in our new world of communications, media entities found on T.V and the internet are rarely heralded for their existential guidance.

It's this predicament that underlies Lost In Translation; meaninglessness is so ripe and ready to consume people and we often don't have the tools to combat this. There is, however, meaning to be found in one another and in the intermittence of the new. This is an idea encapsulated by Bob and Charlotte's friendship, one that has undertones of a romance that never fully flourishes. Much like entertainment, love and relationships can lift us from the currents of time that lead us towards an implication of a pre-determined fate or destiny. However, there is a clear difference in the quality of entertainment and love, and that seems to be predicated on and rooted in our biological make-up; we find greater purpose in one another rather than in distractions or entertainment. This is why there is such a precious sentiment imbued throughout Bob and Charlotte's relationship; despite perceived meaningless, despite inarticulable inner conflicts, when they are together, there is an understanding connection that lifts them away from their worldly problems. This then leaves Lost In Translation to be one of the most intricate and touching assessments of the relationship between time and romance, one that has us find solace in love as a shield from insurmountable existential drama.

On a lasting note, Lost In Translation, at its core, seems to be a story about being trapped and wanting to escape. The trap that our characters, that all people, are in is what we may refer to as life; it is the reality of being a conscious human on Earth. With our cage comes conflicts such as meaninglessness, hopelessness and isolation. These conflicts cannot be quashed as they seem to define the rules of our reality; we are not born biologically tethered to the love of our lives and instilled with ultimate knowledge, purpose and meaning. This leaves people searching for an escape, which translates to the construction of our own meaning and the development and nourishing of loving, purposeful relationships. But, whilst being told this is one thing, pursuing it is another, and so there is no end to this movie, there is only a 100 minute cinematic window through which two characters, maybe ourselves, are lifted away from reality with some hopefully meaningful entertainment.

Coraline - Careful What You Wish For

A young girl is lead to an Other World with Other parents when she follows a mouse through a door in a wall.

I use this word an awful lot, but I believe that there are a lot out there: masterpiece. Coraline is a masterpiece. Not only is this a truly affecting movie with genuine horror imbued into its 3D stop-motion thanks to brilliant artistry at every level of production, but Coraline has a script that is frighteningly dense. Within only 95 minutes, Henry Selick, through adapting Neil Gaiman's book, works an impossible amount of profundity into this seemingly unfathomable fairy tale - one with many dark undertones and, for some, much unnerving subtext. Whilst we've seen complexity in the subtext of Selik's films with The Nightmare Before Christmas, it seems that Coraline goes far beyond this with an abstract collision of so many ideas - too many. So, before we jump right into things, I'll preface by emphasising that I believe this to be unfathomable film, one that cannot be exhausted. And so, despite my efforts here to render as diligently as I can an analysis of this film, there will still be much more for you to explore yourself. Before we begin, I'll warn that this is a very long and circuitous post, so strap yourselves in and get comfortable. With that said, let us start...

The crux of Coraline is, loosely, a psychoanalytical idea of an Oedipal, or an Electra, complex. However, I don't believe that Selik shows a comprehensive adherence to a Freudian or Jungian interpretation of what is supposed to be a detailing of the conflicts that can arise between a mother and daughter as the daughter develops. This is because Freud and Jung emphasised the idea that both mother and daughter were competing for possession of the father. We see no direct implication of this throughout Coraline; whilst the mother, Mel, is possessive over the father, Charlie, to varying degrees across her different representations in the film, Coraline shows no real need to control her father. So, instead of depicting the Electra complex as a conflict seated primarily within Coraline, Selik appeals most explicitly to the over-protective mother archetype - the Oedipal mother - which is bound to psychoanalytical thinking and, self-evidently, ideas such as the Oedipal and Electra complex. In abandoning Freudian and Jungian definitions, Selik abstracts the child out these complexes and focuses on the parents - and such a decision seems to be a sensible one in the modern age (one that has seen a decline in the popularity of psychoanalysis since the former half of the 20th century). This is because, whilst Freud's ideas of the Electra complex and "penis envy" make sense when you envelop yourself into the psychoanalytical axiom or thought structuring, when you take ideas outside of such a context, they become quite sour. This is why a term such as "penis envy" - which suggests that, when a daughter realises that she does not have a penis with which to dominate her mother sexually (as the id would desire), she grows envious - would seem either morally corrupt or misogynist to most people who aren't familiar with psychoanalytical thinking, or simply do not accept it. In taking this element of "penis envy", in turn, a motivation within Coraline to possess her father as a means of embracing heterosexual femininity, Selik then not only makes this film more palatable and less abstract, but manages to add his own nuances onto the character of Coraline that suite her persona rather than reduce her to a mere psychoanalytical archetype. With that briefly outlined, we can then interpret the opening image of the film:

As we will later find out in the story, this doll is a representative of a child which the Other Mother, or Beldam, will use to spy on the represented figure and eventually ensare. The Other Mother, considering her as this alone, an "other mother", is a character that is then quite simple; she is the Oedipal mother. This means that she is over-protective to a degree that will damage her child; she wants them to perpetually be an infant from which she can suck love out of - which is why it is said that mothers want to eat their children in this narrative. This isn't an implication of malevolence. As is well-known by all parents or even anyone that has come into a contact with a cute baby, there is an urge within you to squeeze or bite young infants. Again, this isn't malevolent; you don't want to hurt your baby, rather, you do not know how to deal with such frailty and cuteness that you just have to smush the thing. This type of emotion or feeling leads to what is called a "dimorphous expression", and this idea defines the phenomena of acting with aggression and care towards cuteness. It is then thought that mothers want to bite or squeeze their babies as a way of regulating their reaction to perceived stimuli; the baby is so weak and so you understand that it can be destroyed all too easily - all you'd have to do is squeeze its soft head and it'd die - but at the same time you have an overwhelming urge to protect the baby because it is so vulnerable.